Two days before, the Guardian had come out with an article tackling — and answering — the same question. “Welcome to peep style,” declared Online Fashion Editor Morwenna Ferrier, “a subversive approach to street style, driven by a hunger for a more candid, authentic approach, which focuses on capturing real people in real clothes and — this is key — who aren’t necessarily posing.” Growing weary of the seasonal parade of impeccably styled bloggers, editors, and it-girls, Ferrier explains, photographers are now looking beyond these “peacocks” — as Suzy Menkes calls them — of fashion week for creative inspiration. She concludes, “…if street style [is] to survive, it [has] to evolve.”

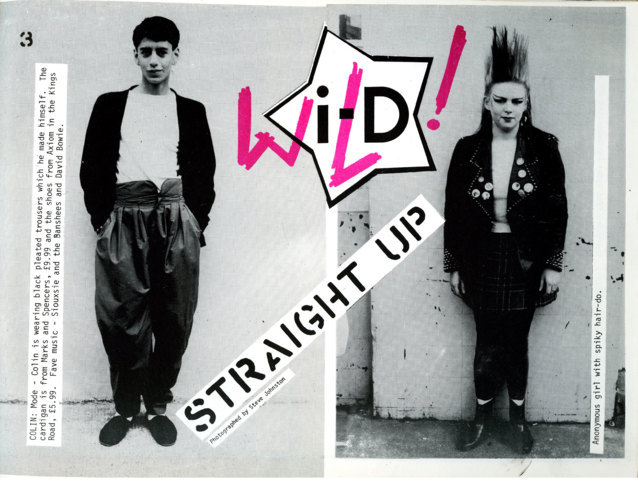

At this point, it’s difficult to imagine a world without the street style that we know and love. Though people have been wearing clothes in public for a while, the concept of street style was only recently imagined by the fashion world. The term first popped up in the 70s, when New York Times photographer Bill Cunningham started snapping candids of stylish people he happened to spot on the street. Then in the early 80s, i-D founder Terry Jones pioneered a new type of fashion photography, The Straight Up. He photographed Punks and New Romantics in their everyday clothes on the streets and in the clubs, melding fashion with documentary and influencing everyone from tabloids to broadsheets and style mags to women’s weeklies.

Until the mid-00s, street style photography existed merely as a novel alternative to the high-octane glamor of editorial photos, presenting clothes as they were worn in real life by stylish, unsuspecting passers-by. Street style blogs, the gateway drugs of the current scene’s explosion, arrived shortly after the arrival of high speed Internet. Is it a coincidence that street style exploded in tandem with the digital age? I think not. Just as the internet provided free and equal access to information, it also provided a free and equal platform of expression, and fashion became more of a direct democracy. Fashion junkies immediately pounced upon what was simple, refreshing, naturally abundant: street style.

Street style remained “indie,” however, until photographers ended up outside of fashion shows, hunting the crème de la crème of street style — the mysterious, glamorous insiders who had the privilege of slinking around in looks straight off the runway. This was when, as Garance Doré once said, street style became fashion week style; when celebrities become involved, things get surreal. Amy O’Dell reported for Buzzfeed that Phil Oh, whose first photos were “actual on-the-street style — people on the street, not at fashion week,” only got his big break when Vogue’s photo editor contacted him about a random picture he’d taken of a group of famous Vogue editors walking through the Tuileries during Paris Fashion Week. “Can you do more of this?” the editor asked. Though street style was becoming more calculated, it was becoming more popular, it was also the first time street style was elevated to editorial levels.

What was once reserved for unknown bloggers like Caroline Blomst and Tommy Ton has totally infiltrated the fashion industry, from magazines to stores to designer influences, and like everything else we consume, we want the street style imagery to appear larger than life. We want the realism of digital with the polish of print, and as a result street style has become a highly profitable industry, and as paradoxical as a carefully curated Instagram. People prepare for candid photographs because of the infinite potential that comes with exposure — after all, street style favourites are the IT-girls of our generation. So they arrive at fashion shows after four hours in hair and makeup, wearing Nike Dunks and dressed like Daphne Guinness, and dazzle effortlessly in front of the cameras because there’s a demand for it, not because they’re bad muses. Proponents of peep style complain that street style has lost its counterculture moxie and ability to inspire, that subjects are posing and their outfits premeditated, and that the “aspirational” excuse is code for “you’re not good enough without this.” That all may be, but that still doesn’t mean that the street style we see isn’t real — a twist that could give bored photographers something to chew on.

Otherwise, the alternative. Ferrier names pioneers of the peep style movement the normcore of fashion photography: French-American fashion photographer David Luraschi; LA-based photographer Alkistis Tsitouri; and London-based Alex Sturrock. Luraschi only shoots from behind, Tsitouri’s subjects are stiff and forward-facing, and Sturrock, the extremist of the bunch, produces photos that are so far from contrived that some look like accidents. They’re indiscriminate about the age, class, race, gender, etc. of their subjects, avoid peacocks, and strive for naturalism. Their inspiration is often abstract, a silhouette, an expression, or just the specific context of the photo. Their work would look perfectly at home in a contemporary art gallery, but it’s hard to imagine how peep style could replace street style in the fashion world, as Ferrier suggests, unless it evolves into some kind of glorified paparazzi.

On the other hand, the normcore trend turned out to be the surprising toast of 2014, so peep style might have a decent shot. With slight alterations, of course. Although New York magazine originally defined normcore as, “Mall clothes. Blank clothes. The kind of dad-brand non-style you might have once associated with Jerry Seinfeld…mock turtlenecks with Tevas and Patagonia windbreakers; Uniqlo khakis with New Balance sneakers or Crocs and souvenir-stand baseball caps,” your flyover state parents barely had time to bask in the glow of their neon fanny packs before fashion repackaged the trend into something digestible, like Céline birkenstocks. Fashion can’t support itself by being literal.

If anyone believes that the fate of street style is so black and white that its alternative happens to rhyme with it, then they’re not seeing the larger picture, which still includes Bill Cunningham and his film camera. Street style isn’t a religion or a brand – it’s a concept that we only decided existed a short while ago, and there’s no “better” approach to street style, only more convenient ones.

Credits

Text Hannah Ghorashi

Design Terry Jones

[The i-D One Issue, no. 1, August 1980]