Camille Bidault-Waddington was on set one afternoon, half-watching the model, half-watching the photographer, when she realized her iPhone was full of accidental snapshots: elbows lifting, lenses tilting, bodies folding into strange, efficient shapes. It was the kind of backstage detritus most people delete without thinking. Camille didn’t. Instead, she followed the instinct that has shaped her career for more than two decades—a stylist’s gift for noticing the overlooked.

Bidault-Waddington’s unique perspective and broad body of work have made her one of the most esteemed stylists of her generation. Since moving from Paris to London in the late ’90s, she has treated styling as a form of storytelling. Her collaborations read like a syllabus of contemporary photography—Jamie Hawkesworth, Nick Knight, Harley Weir, David Sims, Inez & Vinoodh—each shaped by her intuitive sense of mood, character, and the cultural echoes of art, literature, and photography.

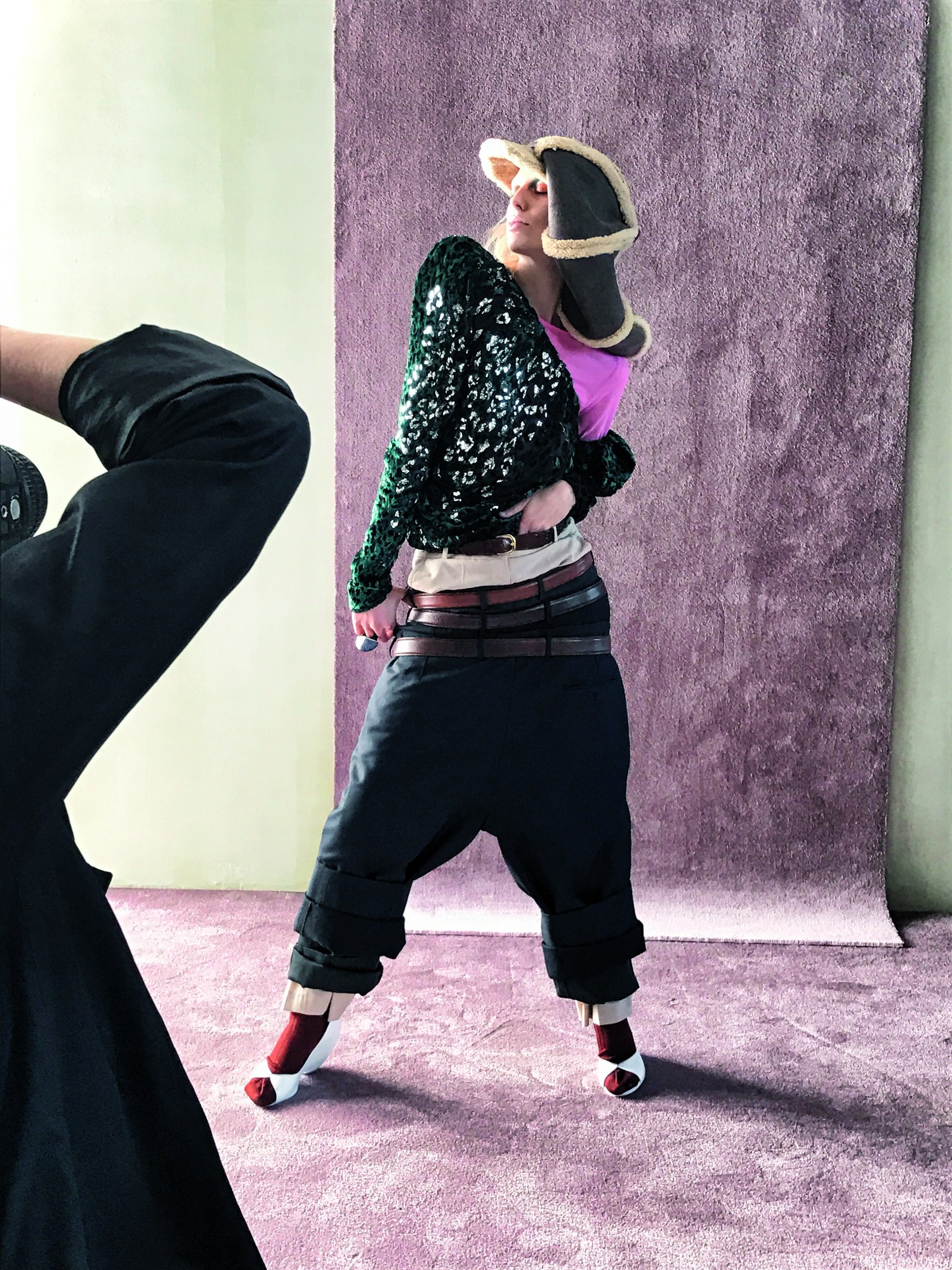

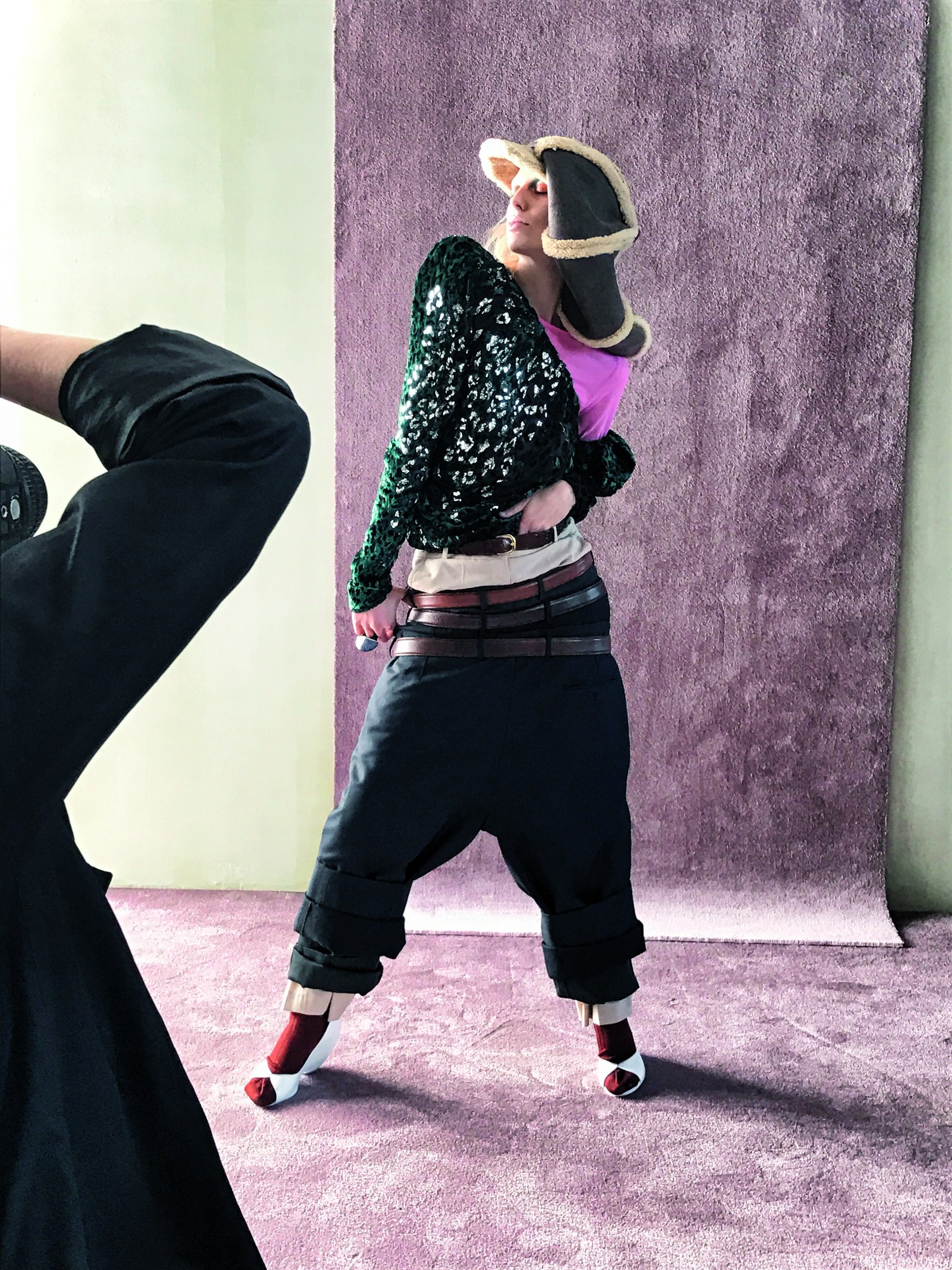

With The Office, her new book published by Empire Books and designed by Syndicat, she does something unexpected. She turns her camera away from fashion’s glossy surface and toward the people who construct it. Over the past decade, she has quietly photographed nearly two hundred photographers at work, using nothing more than her iPhone. The result is a portrait of fashion as a living ecosystem.

We caught up with Bidault-Waddington about instinct, authorship, invisible labor, iPhones, and the strange, beautiful choreography that takes place just outside the frame.

Alex Kessler: Can you tell us about The Officeand what inspired the project?

Camille Bidault-Waddington: The Office is a book of snaps I took almost without noticing—on set, in studios, on location. Making a fashion image involves a whole team, so many brains and arms. A stylist watches the model through the photographer’s angle to participate in the direction of the image. iPhones are like notebooks.

When I edited my phone, I realized I had lots of photographers and made an “album.” I love making albums—some worse than others, like “bald men in Berlin” or “ceiling bulbs.” Michael Amzalag saw one of the photographers and connected me with Sacha Léopold and François Havegeer from Empire Books and Syndicat.

What made you turn the camera toward photographers instead of clothes or models?

I didn’t really turn the camera toward them; they just happened to be in the frame. I was keeping a reminder of the model. A stylist is often the photographer’s shadow… Both look at the model, the image, the space, the mood.

Why did you decide on an iPhone as a creative tool?

I was a BlackBerry girl because I love words, then moved to iPhone for practical reasons. I discovered the fun of shooting things, I’ve even shot fashion images for Purple. Maybe in those snaps there’s a frustration of not shooting the picture myself—it’s unconscious.

What gestures or behind-the-scenes moments stood out most?

The invisible part is time. There’s prepping, waiting, rotation… It can go fast or slow. Everyone feels it differently. It’s a mix of human energies.

Because these pictures began as instinctive, incidental snaps, how do you think your stylist’s perspective shaped the way photographers appeared in your frame?

My stylist perspective is that I didn’t really see the photographers—I was looking at the model or set. Photographers wear discreet, practical clothes; shoots are physical. They’re hunting for a moment. Hunters don’t wear brash clothes.

How did photographers react when they found out you were putting this together?

I was impressed. Most said yes without even asking to see the photo. They respected the concept without vanity, even though they’re in weird gestures or body shapes. I thought that was cool.

If this book represents an “office,” how would you describe the office?

It’s an uncomfortable huge room filled with equipment, or a field in the countryside.

Do you think people are more interested in the process behind fashion images than the final result?

Maybe. People spy, stalk, look at influencers, want to see what’s real in a world of Photoshop and filters.

What was it like working with Syndicat studio on the design?

I shot the snaps; Sacha and François did the edit. Syndicat art-directed the project — they worked more than me! Victoire Le Bars wrote a cool text. I just did a silly little text about my physical presence.

What do you hope readers take away from this often-invisible side of image-making?

That a fashion photo is created by many human brains and bodies—designers, models, assistants, PR, casting. It’s a cocktail of energy. An image might last two seconds on Instagram or much longer in the mind. I remember lots of fashion images, probably because I don’t buy many clothes and I love photography.

Is there another hidden part of fashion you’d like to explore?

I think I’m done with fashion exploration. I love the book because I didn’t do it on purpose. I’m happy to show a landscape of photographers of a certain time, with a strong amount of female photographers. It’s very important to me.