Banksy has graced the world with a fresh bit of graffiti on the wall of the Barbican to “celebrate” Boom for Real, the new Basquiat retrospective, opening to the public tomorrow. Banksy’s deep and thought-provoking new artwork features two police officers frisking a figure lifted from a Basquiat self-portrait. This is the closest the exhibition comes to addressing the racism Basquiat suffered at the hands of the police, as a kid, and at the hands of the art world too, when he was still really just a kid. He died at 27, of a drug overdose, which is no age really.

Basquiat’s biography is a problem if you want to enjoy the paintings, because he’s not really a painter anymore, he’s a myth; and the myth and money ($110m for a painting!) clouds everything.

The myth then: he was young and he was beautiful. He was dating Madonna and living in a NYC squat in 81 and painting in Armani suits and shooting up and listening to hip-hop and playing in a no wave band at the Mudd Club. Who can blame him for any of that? The problem is, how do you surmount that and climb over that and get on the other side and appreciate the paintings? How to acknowledge the mythology and put the focus on Basquiat as an artist? Boom For Real is, unfortunately, all context, all Downtown 81, all Madonna, Mudd Club, Armani and Andy.

I can’t help but feel we should be bored of this hagiography of New York by now, but at the Barbican do we have to negotiate a whole floor of it before we get to the paintings. If I wanted to watch Downtown 81 I would have stayed at home and streamed it on YouTube. A Basquiat exhibition should be a chance to look at the paintings; so many are in private hands that it takes a big retrospective like this to unite the work.

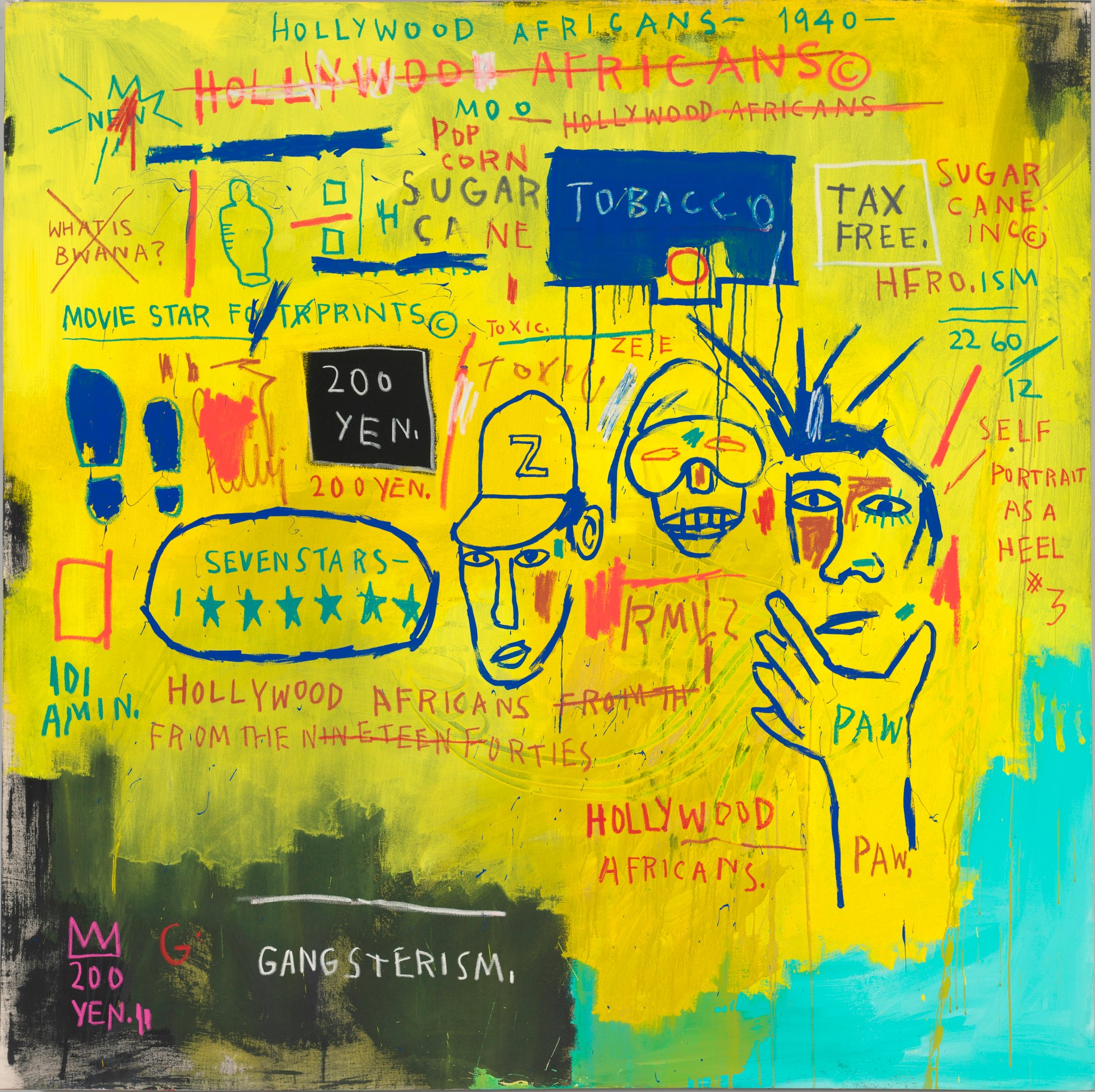

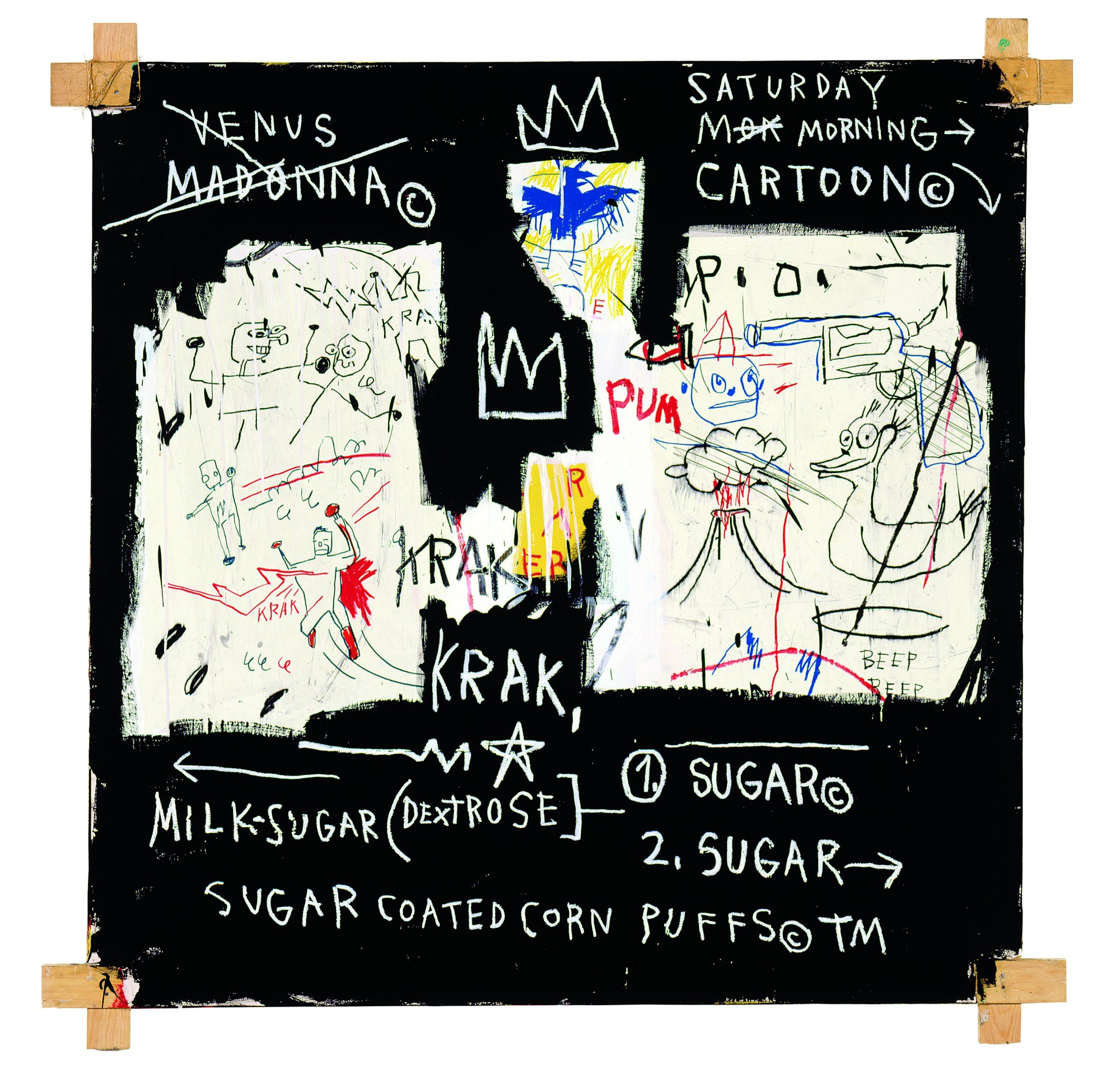

You enter and you’re ushered upstairs and the first room, actually, is dedicated to New York/New Wave, and his work for the group exhibition at MoMA PS1 is shown here in its almost entirety for the first time in 35 years. It was the show that launched him in the art world, and turned him from New York’s hottest graffiti artist into New York’s hottest art star. All those things in the paintings we love so much are here, almost, gestating and being worked over and considered. The unusual materials, the complexity of arrangement, the depth of meaning, allusion and reference. The textual density like an explosion of fragments of a poetry book, everything just about holding itself together, stretching out a welcoming hand to the viewer to interpret them. There’s so much to look at in the paintings, it’s overwhelming and deeply affecting, everything dissipates in their beauty.

Writing about the New York/New Wave exhibition in the Village Voice, Peter Schjeldahl said, “I would not have suspected from Samo’s grotty defacements of my neighbourhood the graphic and painterly talents revealed here.” We’re starting to get to the heart of the whole biographical drama now. Reading between the lines, Peter Schjeldahl wouldn’t have expected the young, black graffiti writer to be a good painter.

Are we more comfortable with the idea of the young, black painter if he’s modelled as a cool counter-cultural, figure? Do we still need to rehash and go over this every single time we’re going to have to a Basquiat retrospective?

This is the problem with the exhibition. So many videos of Basquiat painting, at work, hanging around, looking cool. Why aren’t we looking into the context of racism in the art world in the exhibition? Because, more than CBGBs and the Mudd Club and Area and Andy and Madonna, this is real heartbreaking crux of the biography of Basquiat. It’s all between the lines and glossed over and never really addressed in what’s presented here, when, downstairs, in the rooms properly dedicated to the paintings, it explodes.

There are vitrines full of dull ephemera, and a wall full of polaroids of other cool kids on the scene. Do we need to watch TV Party again? Do we need to see that picture of Andy Warhol and Jean Michel dressed up as boxers again?

It’s not like New York City in the early 80s has drifted out of living or cultural memory.

It’s upsetting, because you don’t get retrospectives like this for white painters or white artists. David Hockney at the Tate didn’t have rooms full of pictures of his friends, it had his paintings. Does Jeff Koons have to deal with this? And it’s strange, as these are hardly unknown or lost cultural touchstones that we need to anchor ourselves in to get to grips with the work.

And it jars when you get to see the paintings, properly, all together, because when you eventually get to the rooms full of paintings, they scream and rail and fight against racism the rest of the show ignores. They explore the history of race, they link racism now across the racism past.

Then you look up, and there’s a giant quote on the wall about Miles Davis, and another about how Basquiat never went to art school. It’s everything he had to play up to to get noticed in the art world because the art world can be incredibly racist. It’s everything he tried to escape from once he was famous, but he couldn’t, because the art world is incredibly racist.

Let a beautiful painting be a beautiful painting, and let a painter exhibit his paintings.

And for all the rooms of context, not once do they talk about racism. No references to the general racism of the era. The whiteness of the art world. For all the references to graffiti and hip-hop, they never talk about how Jean Michel’s friend, Michael Stewart, was beaten to death by police for tagging on the subway. They never talk about the poverty and death of Downtown 81, only the glamour and grit and the coolness. But there are Basquiat skateboards in the gift shop, which is what he would have wanted.

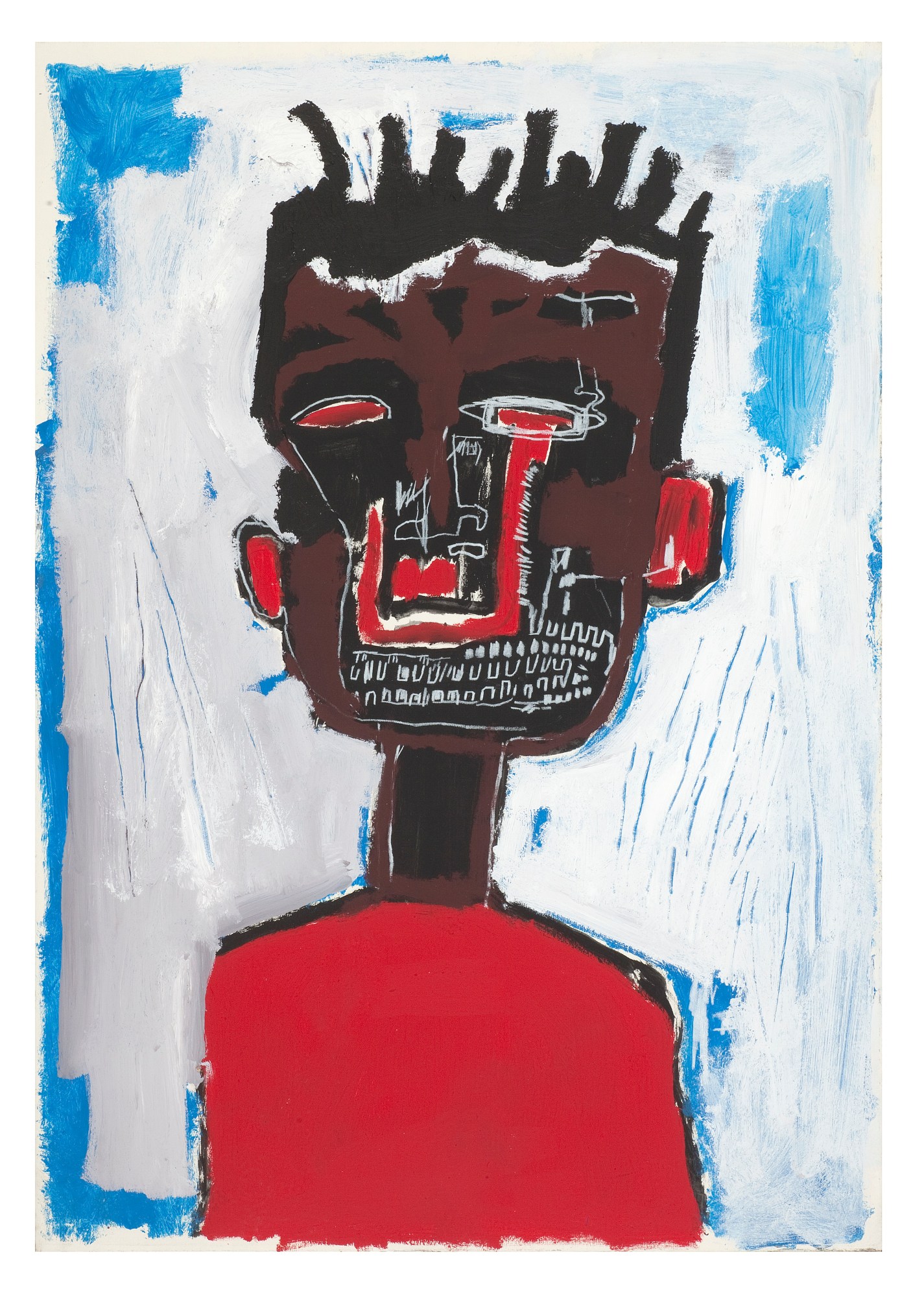

But Basquiat’s paintings are overflowing with all of this, it’s impossible not to talk about it. His self-portraits, a black abyss for a head. He painted black sportsmen and boxers and turned them into black kings and heroes. He painted about Jesse Owens, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong. He painted about Moses, slavery, and the Egyptians; about Lincoln and the abolitionist movement in America; about Britain’s colonial past. He devours and explores and paints race beautifully, angrily, with disgust and depth and feeling, and he finds beauty in blackness.

This is the context Boom for Real should be providing. If there’s any relevance to be found in rehashing NYC in the era of Basquiat, it’s to pick apart the problems, and ask ourselves why these problems still persist. Racist artworld, racist cops, police brutality. Don’t mythologise Downtown 81. Look at the paintings.

Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, produced and with cover artwork by Jean-Michel Basquiat, beat Bop record, 1983, Courtesy Jennifer Von Holstein