In David Gordon Green’s upcoming sequel to Halloween, marking Jamie Lee Curtis’s return to the horror franchise that made her name, Laurie Strode is reintroduced as having meticulously prepared for and almost willed the escape of Michael Myers, the incarcerated killer who stalked and murdered her friends 40 years earlier. Her granddaughter notes that everyone in her family “turns into a nutcase” around October 31st, and Curtis herself has promised that the film will be driven by themes of PTSD and the deep-seated effects of trauma in a way that many of the previous Halloweens were not.

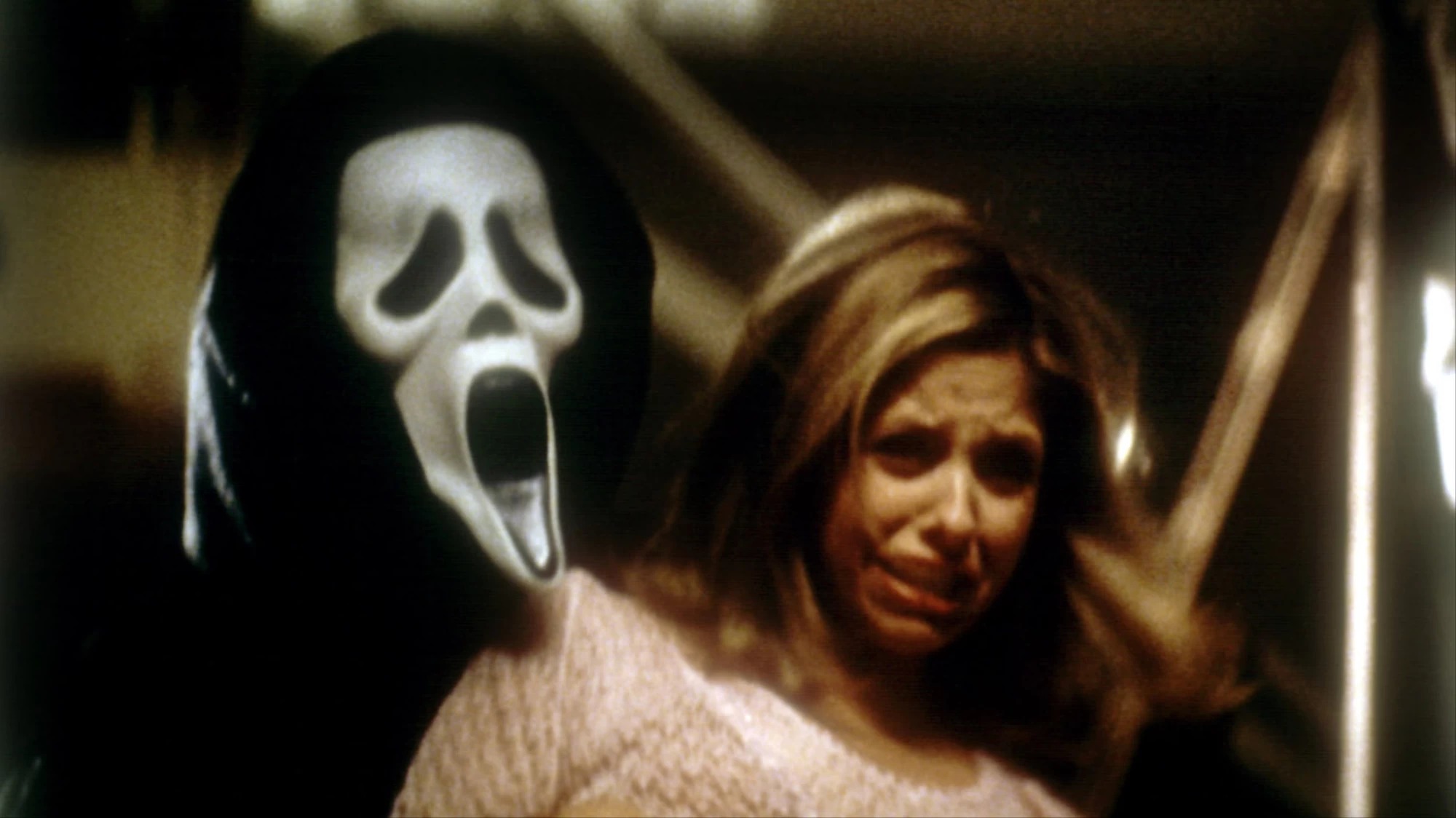

The film is a 40-years-in-the-making sequel to the original slasher classic, one described as returning the franchise to its terrifying, slow-burn roots. But it’s also indebted in many respects to the slasher boom of the 90s, an era of cinema that began with Scream, birthed Halloween H20, Urban Legend, and I Know What You Did Last Summer, and, unlike much of its slasher lineage, largely foregrounded difficult and complex female characters above the men trying to kill them.

This was an era of enormously commercial horror, one that rescued slasher movies from dusty fates on the bottom shelf at your local Blockbuster and turned them into must-see events. They were films covered in the media as breathlessly as a Marvel movie today. It was also an era that introduced a degree of compassion to a genre typically dominated by gratuitous nudity, problematic sexual politics, and graphic violence.

The Scream era and the slasher films of the 70s and 80s that loosely inspired them both depicted violence, but while the latter lingered overwhelmingly on the act of it, the former was more interested in its psychological and cultural effect. Written overwhelmingly by gay men like 90s teen stalwart Kevin Williamson and starring teen idols from Dawson’s Creek, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and commercials for Noxema, these were movies beloved by demographics often underserved by horror filmmakers of the past, but largely sneered at by gorehounds.

“When I got into the horror community I thought we’d all hold hands, skipping through a field talking about how great Scream is — but that was very much not the case,” remembers Alexandra West, the author of The 1990s Teen Horror Cycle: Final Girls and a New Hollywood Formula, the first academic text to specifically explore the Scream era. “I quickly learned to not mention those films. Looking back I see the gatekeeping that was happening by those who were at the top of the horror community at that time.”

Despite the genre’s fondness for female leads who outlived their friends and fought and clawed their way to victory against a killer (which were dubbed “final girls” by academic Carol L. Clover in her seminal slasher movie thesis Men, Women and Chainsaws), women were formally never the true stars of the horror genre. Outside of someone like Laurie Strode, slasher movie leads were often interchangeable, and endlessly replaced in every additional sequel. While villains like Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, and Leatherface became the de facto draw for their respective franchises. On screen, these villains regularly stabbed, gutted, and terrorized scantily clad young women, but were also gimmicky pop culture heroes. (Fun fact: Jason Voorhees was once face of Mentos.)

Scream shifted the rule book in that we were asked to root for middle-America teen Sidney Prescott, rather than the masked killer stalking her. Played by Neve Campbell (who, at the time, was starring in the FOX family drama Party of Five and coming off the seminal teen movie The Craft), Sidney had more in common with cinematic heroines like Sarah Connor and Ellen Ripley than the final girls that came before her. The character evolved from a broken girl-next-door haunted by her mother’s murder in the first Scream to a powerful figure of survival and psychological strength in 2011’s Scream 4. And despite the horror genre’s regressive rules when it comes to sexually active young women, Sidney loses her virginity to her secretly murderous boyfriend in Scream and isn’t punished for it with death. She puts a bullet in his head instead.

Sidney was joined by Gale Weathers, a brilliantly cut-throat tabloid reporter played by Courteney Cox that the franchise never judged for being unapologetically ambitious, and Rose McGowan’s Tatum, Sidney’s snarky, compassionate, and sex-positive best friend. These were female characters with personalities and agency. Women who spoke to one another and fought back against the abuse and savagery of the men around them. When Tatum is squished to death by a garage door just before the film’s climax, it is a tragic, horrifying closer for a character we had long rooted for, and speaks to the efforts Williamson and director Wes Craven went to in humanizing their cast.

“No one discusses how disconnected people are when they watch horror films,” McGowan writes in her memoir Brave. “God forbid you watch someone die awfully and you feel something… What I thought the original Scream did very well was to make you care about each character. We weren’t disposable.”

At one point in The 1990s Teen Horror Cycle, West curates an array of negative quotes from horror critics who have dubbed the Scream cycle “pandering,” “frustrating,” and even “misandrist.” Most major critics, however, by and large praised Scream, but struggled to offer much support for its cinematic offspring. While the era’s reputation among Fangoria types — the kind of fans who are able to perform a line-by-line reenactment of I Spit on Your Grave on command — has always tended to be sour.

West isn’t surprised about Scream’s reputation among fanboys. “Female narratives are taken less seriously than white, hetero-male narratives and the 90s spoke to a generation of teens who got to see some aspects of the dark parts of their lives represented on screen,” she says. “A lot of male audiences and men in general are deeply uncomfortable with female trauma because engaging with it means culpability, acknowledgement, and finding out how to help. I think it’s easier for straight white men who are generally assumed to be horror’s bread and butter to find sympathy with Jason Voorhees and cheer him on than it is for them to understand the complexities of varied experiences.”

“Female narratives are taken less seriously than white, hetero-male narratives.”

In the wake of Scream’s box office success, rival studios rushed to capitalise on the slasher boom, realizing the financial potential of casting recognisable but inexpensive actors in low-budget thrillers. In the 21 years since its release, Scream’s reputation has only grown in critical circles, but its imitators haven’t been as lucky, despite their fair share of rewarding qualities. It’s common to forget that films like I Know What You Did Last Summer, Urban Legend, and Halloween H20 weren’t just indebted to Scream’s self-referential, WB-network glossiness, but also to its psychological depth.

I Know What You Did Last Summer is often talked about as Scream’s dumber sibling, featuring Freddie Prinze Jr. emoting and Soul Asylum on the soundtrack. Truthfully, all of that is correct. But it also substantially traffics in feelings of emotional damage, with characters constantly circling full-blown mental breakdown. A year after killing a man in a hit-and-run accident and dumping his body at sea, Jennifer Love Hewitt’s Julie James is a pill-popping depressive devastated by her own mistakes. Her best friend Helen, played by a resilient and endearing Sarah Michelle Gellar, has had her post-high school dreams abruptly dashed. She went to New York to become a star, but was quickly forced to slump back home, fruitlessly saving up money while working the cash register at her older sister’s clothing store.

Like Scream, it is a film that deliberately upends expectations. Rather than Julie’s frayed relationship with love interest Ray (played by Prinze Jr.), the film is deeper invested in the gradual mending of Julie and Helen’s friendship, while Anne Heche’s haunting cameo as a backwoods recluse is played less as a scary red herring and more as a tragic mirror for Julie’s self-enforced isolation.

In 1998’s Urban Legend, starring an in-hindsight wacky cast that included Jared Leto, Tara Reid, and Joshua Jackson, a fatal car accident spins two strangers into varying forms of PTSD. Alicia Witt’s final girl Natalie is left guilty and broken by the incident, in which she and a friend’s highway prank went tragically awry, while Rebecca Gayheart’s Brenda, whose fiancee was killed in the prank, is driven to madness. That Urban Legend makes its hero somewhat responsible for her own torment and the murders of a number of innocent people is one of its many subversive pleasures.

Cherry Falls, shot for theatres in 1999 but ultimately released via cable television in 2000, cast the wonderful Brittany Murphy as one of a number of small-town teenagers punished for the misdeeds of their parents. Like Scream, the problematic sexual politics of the horror genre are upended, with the film’s killer deliberately targeting virgins rather than those savvy enough to pop their cherries. And the killer’s motivation, revenge for the rape of his mother by the town’s frat-bro elite, is fascinatingly difficult to completely condemn.

Halloween H20, released in 1998, saw Jamie Lee Curtis returning to the role of Laurie Strode, in a film that has subsequently been wiped from franchise continuity. And while it is stocked with chase sequences, meta humour, and future stars (including Michelle Williams and Joseph Gordon-Levitt), it is largely driven by Laurie’s own trauma. Set 20 years after the original film, she is living under an alias, cursed by memories of her first encounter with Michael Myers, and suffering from alcoholism. Curtis recently told Variety that the film was a “money gig”, but it’s a statement that does something of a disservice to the film’s many strengths. It works in many ways as the perfect closer to the Halloween franchise, with Laurie finally achieving some semblance of peace after a lifetime of pain.

Like most horror trends, the Scream era slasher boom eventually faded out. The murders of 15 high school students at Columbine High School in April 1999 suddenly took youth violence out of movie theatres and into the real world, with right-wing reactionaries claiming Hollywood was partly to blame for the tragedy. Whether it was justified or not, the film industry decided to turn a corner in response.

Scream 3, which originally focused on a cult of high schoolers plotting to kill Sidney, was re-written as a Hollywood satire, the franchise’s typical violence drastically defanged. Teen movies featuring ruthless adolescents, from Kevin Williamson’s black comedy Teaching Mrs Tingle to the James Marsden-led thriller Gossip, were given little promotion and ultimately flopped, while a third I Know What You Did Last Summer was quietly shelved. As the nightly news reminded us of the banal evils of the real world, we collectively decided we wanted to laugh rather than scream. Scary Movie, the Wayans Brothers comedy inspired by the 90s slasher boom, became one of the runaway smashes of 2000, grossing $300 million worldwide.

Horror has continued to evolve in the decades since, transitioning out of slasher mysteries to Japanese-inspired ghost stories and the grungy torture porn of Eli Roth and Leigh Whannell. The late aughts saw an influx of remakes of 1970s classics like Prom Night, Black Christmas, and The Hills Have Eyes, while the Insidious and Conjuring franchises have marked a return to bump-in-the-night haunted house chillers.

But while the Scream boom often feels like a moment lost in time, there does appear to be a resurgence in sight. The character-driven feminism of Scream and the films it influenced can be seen in the maternal strength displayed by Emily Blunt in this year’s breakout horror smash A Quiet Place, and Taissa Farmiga’s haunted memories of her late mother in 2015’s The Final Girls (a 1980s slasher homage in theory, but far more in keeping with its 1990’s ancestry than anything else).

Happy Death Day, the Blumhouse sleeper hit from last fall, resurrected the whodunit mystery of Scream and wrapped it in a high-concept time loop premise, but still made sure to write Jessica Rothe’s terrorised final girl as a funny, resilient heroine we liked to spend time with. The return of Halloween, a relaunch of MTV’s Scream TV series, and a rumoured reboot of I Know What You Did Last Summer give even stronger indication that a return to the depth and aesthetics of the Scream boom could be on the horizon. It’s a thought that excites Alexandra West. “ Happy Death Day reminded me a lot of the tone and strengths of the films I loved in the 90s,” she says, “and I have hope that more filmmakers will follow suit, giving characters power over genre conventions. The generation who came of age while these films were getting released are [now] becoming the tastemakers.”

This article originally appeared on i-D US.