In 1994, two teenagers travelled from their home city of Oxford to west London in search of someone to kill. Their plan – part of a made-up initiation to join the Special Air Service – was to find a pimp or drug dealer who could become their victim. When their search was fruitless, the two instead assaulted Egyptian chef Mohamed el-Sayed while his car had paused at an intersection, stabbing him to death before returning to Oxford.

The story became a sensation in the British media, with the killers cast by tabloid newspapers as a modern-day Leopold and Loeb. Soon, interest from the filmmaking world followed. Decades of true-crime dramatisations and documentaries have taught us how to make such a movie: a recounting of events that reveals the humanity behind the headline, deepens the personhood of the deceased, and gains some iota of insight on his killers.

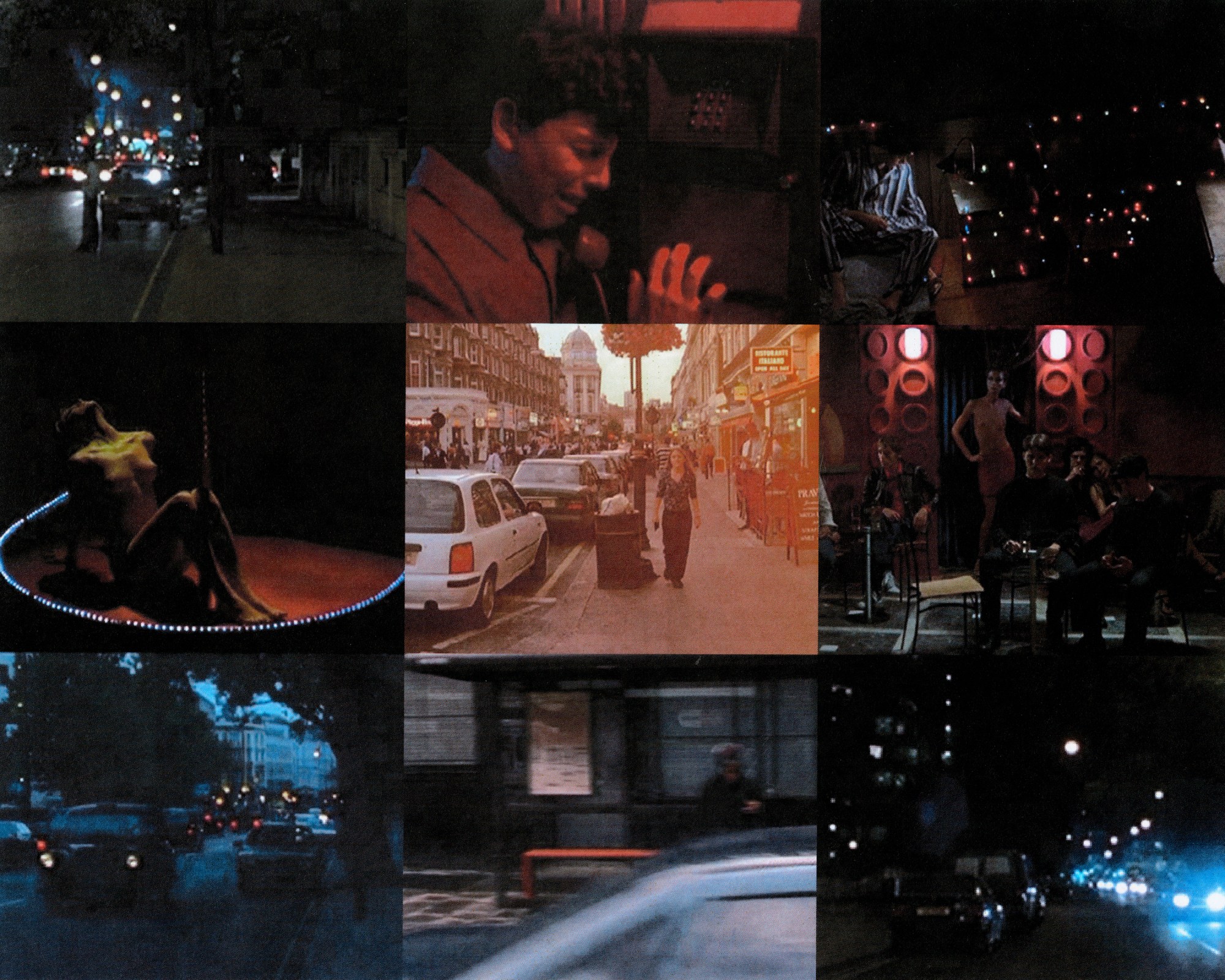

A certain 24-year-old recent graduate — tall, slim and handsome, his head wreathed with long flowing tresses — named Luca Guadagnino figured he’d take a different tack. His 1999 debut feature The Protagonists assumes a more expansive perspective on the incident by going meta, following a film crew in the process of making a micro-budget project about Mohamed’s murder. Rather than playing armchair diagnostician, Luca’s resulting hybrid of artifice and reality probes some uncomfortably tender parts of our psyche with a daring ambiguity, in particular the nasty impulse to gawk at other people’s tragedy as our own diversion. The reviews were scathing (“Oh dear,” Time Out wrote at the time), with some accusing Luca of indulging in the same exploitation he set out to indict with his unorthodox blurring of the lines between fiction and fact. A quarter-century later, however, any transgressions seem relatively tame in comparison to the slow-moving collapse of documentary ethics since then. For worse or for better, he was mainly guilty of being ahead of his time.

The production took shape the way independent art should, with a group of motivated friends itching to put their collected talents to use. Luca met cinematographer Paolo Bravi years earlier through art historian Viviana Gravano, he met longtime editor Walter Fasano through Paolo, and their clique continued to expand over long nights of good-natured, tipsy debate at restaurants and bars around Rome. “In the Mouth of Madness by John Carpenter had just been released, and Luca and I loved it, but our contemporary Francesco [Munzi] and Paolo hated it,” Walter says from his home in Italy. “My friendship with Luca was born on such a night. He came to use the toilet in my apartment and stared at my VHS collection, saying something like, ‘I approve of ninety percent of your collection.’ And I said, ‘Thank you very much. There’s the toilet.’ Each of us had a different role, and I was a bit like the Tom Hagen, the consiglieri to this group.”

Paolo affectionately dubbed The Protagonists‘ filmmaking team as the “Guadagnino royal court”. Together, they packed themselves into a single living space for the film’s shoot, from the streets of London to a studio space in Rome. (Paolo remembers these days as “very bohemian,” though he’s quick to clarify: “It was not exactly like a 60s commune. Everyone had their own room.”) The most noteworthy outsider was Tilda Swinton, portraying the director-slash-star of the film within the film when not breastfeeding between shots or minding an eleven-month old Honor Swinton-Byrne as she toddled around on set. At that early juncture of her career, Swinton’s main credits came from queer cult classic Orlando and her arty collaborations with Derek Jarman, but as Walter explains, “To us, she was already a movie star.”

“Luca was born ready for directing.”

WALTER fASANO

Having hired his friends instead of strangers, Luca wasn’t shy to test their patience with his unpredictable all-hours enthusiasm. It wasn’t uncommon for him to begin his morning by barging in on his slumbering wardrobe supervisor to ask her opinion on the day’s outfit, chuckling as she cursed at him to get out. Walter, who mostly recalls an “atmosphere of harmony, happiness, and friendship,” nonetheless remembers one work day that took an abrupt pause: “Luca came to the editing room late one morning, which was on the ninth floor of a building with a multiplex on the ground floor, five screens. He checked which films were playing, and Luca told everyone, ‘Okay, at four o’clock, we’re all breaking to go see Armageddon.’ And I said, ‘Luca, we are editing the middle of this scene, how can we go?’ And he says, ‘You must go. You’ll find inspiration!’ We all go down, and I’m falling asleep five minutes after the beginning of the film, then waking up right as it ends. Maybe I got some inspiration from it in my sleep.”

Despite their modest funding (“You can tell the budget was low, and Italian low-budget is even lower than American low-budget,” Paolo laughs), the crew showed the famed Italian hospitality toward all their visitors, including singer Jhelisa, who dropped by to dance in one of the expressionistic sequences diverging from the plot. Best known at the time for her guest appearances on labelmate Björk’s studio debut, Jhelisa’s music caught Luca’s ear during one of his many nights on the local dancefloors, and he resolved to find a place for her. “Luca included me with everything, like I was any other cast member!” she tells i-D. “On an American set, I don’t see that happening. Before my scene, I remember Tilda going up on the stage and telling everyone, ‘And now, introducing: Jhelisa!’ The vibe was right, and Luca got enchanted. What could’ve been a tiny part, he chose to make that a whole moment.”

For some of the film’s more ardent opponents, Jhelisa’s musical interlude was the beginning of the problems, put forth as a prime example of Luca’s misapplied focus. In choosing to follow the film crew instead of telling the story in a more conventional fashion, he’d prioritised his own heady experimentation over basic compassion for the victim. A modern take from one Letterboxd user reiterates the initial objections, singling out an interview with Mohamed el-Syed’s widow shot as the image on a video monitor instead of directly at her, a deconstructive gesture that can scan as callous. “In the end, the interview with the victim’s wife, we shot on miniDV in the real house of the real person,” Paolo recalls. “I was interested to hear what the critics would think of this, whether they would find it ethical.” (Other knocks against Luca, which took him to task for perceived excesses of style, smack of concealed homophobia.)

Viewed in light of a decade of Netflix-produced assembly-line documentaries making ghoulishly disposable content out of real people’s darkest hours, The Protagonists now looks most like brutal prophecy, an indictment of the invasive impulse laundered by the creative process. It’s equally prescient about the bright future awaiting Luca, who’d revisit components of his debut so subtly that their recurrence may very well be subconscious; one jarring pan during a conversation about homicide wanders to land on the exterior of a T.G.I. Friday’s chain restaurant, as if serving up a deep-fried appetiser to the Applebee’s-set confrontation in Challengers.

As a whole, the film is more precisely predictive of Luca’s style — his spontaneity, his heedless embrace of sensation, and his overall self-assurance. He may have rubbed some the wrong way by withholding a cogent, overt thesis for more uncertain pondering, but even from his earliest days, he knew exactly which buttons he wanted to push. “Luca was born confident,” Walter says. “You know the line from Big Trouble in Little China? Kurt Russell says, ‘I was born ready.’ That’s exactly appropriate for Luca: he really was born ready for directing.”