Remember in 2014 when the Stefan Simchowitz art flipping scandal blew up in public, with Jerry Saltz’s article in New York magazine pinpointing a moment in art collecting, and art, which Saltz arranged under the umbrella of “New Cynicism”. A new type of art coming out of the hyperreal sprawl of Los Angeles was being inflated and pumped up, the dazzling façade of a pyramid scheme designed to make the same rich white men types, richer, in the same way that art as a luxury good has often functioned throughout modern history. Flipping, if you didn’t know, is the practice of buying lots of work by young artists cheaply, and selling them on for profit as soon as their prices start to rise. The ugliest symptom of art as a commodity.

The outrage this time was, in part, due to the fact that this staid, relentlessly unimaginative mode of wealth production was being facilitated through the supposedly radical work associated with online art practices. The association being made was that the method of exhibition and dissemination of the work online — curtailing the power of institutional and commercial gallery systems — radically destabilised the status quo.

The Simchowitz scandal reminded us that power balances were still unchanged. Perhaps there were less institutions to go through, or seals of approvals needed, but fundamentally things were only being side stepped to reach the same end point – high prices and secondary market auctions – the institutions maintaining art as commodity remain the source of much power, thus directing much of the art market.

The type of art that was primed for this type of rapid circulation was the type that perhaps wasn’t dependent on the internet for a mode of display, but instead ‘looked like’ the internet, and photographed well, and thus was primed for online art image-sharing on sites like Contemporary Art Daily. And it was really apt if it was a painting, because, painting sells. It was a form that married equally well with another long-standing contemporary art consumer choice, abstract art.

Abstract art not only points to a decidedly male writing of art history (it’s the Rothkos that go for loads, etc.), but also a decidedly imperialistic one – the CIA involvement with US abstract American artists is too perhaps the most political story behind some of the work. What was originally a rumour was confirmed around 40 years later as fact, American modern art was promoted by the CIA as part of their cultural-cold war against the Soviets.

At its core abstract art didn’t set out to be quite so apathetic as many experience it to be now, but art quite frankly is not autonomous, and some more conservative elements of the art buying elite are financially more able to consume abstract art as an irreverent design feature of a home. 2014 was the pinnacle of a new wave of neo-abstraction that was supposedly in reference to the technocratic first world problems of many in the West. It was inspired by new technologies, big data, algorithms, etc, it outsourced the abstraction via techy processes, and often made use of new or unusual materials.

The return of figuration is something that has been slowly seeping into art over the last year or so, initially through post internet practices that began employing drawing amongst text, craft and video practices – bringing a welcome relief from capitalist realist found object practices (think Tumblr IRL) – of artists such as Bunny Rogers, Diamond Stingily, Jasper Spicero, and Andrea Crespo. But in 2016 that slow seepage has become a dominant trend.

We can also for a moment, think that art is not solely obsessed with the cult of youth, as exhibitions have dug up slightly under-recognised older artists and confidently shown young artists whose interest in materiality and human forms no longer suggest naivety or lack of contemporaneity. This has found greater validity through the cross-generational spread that current hot figurative painters provide such as Hamishi Farah and Valentina Liernur.

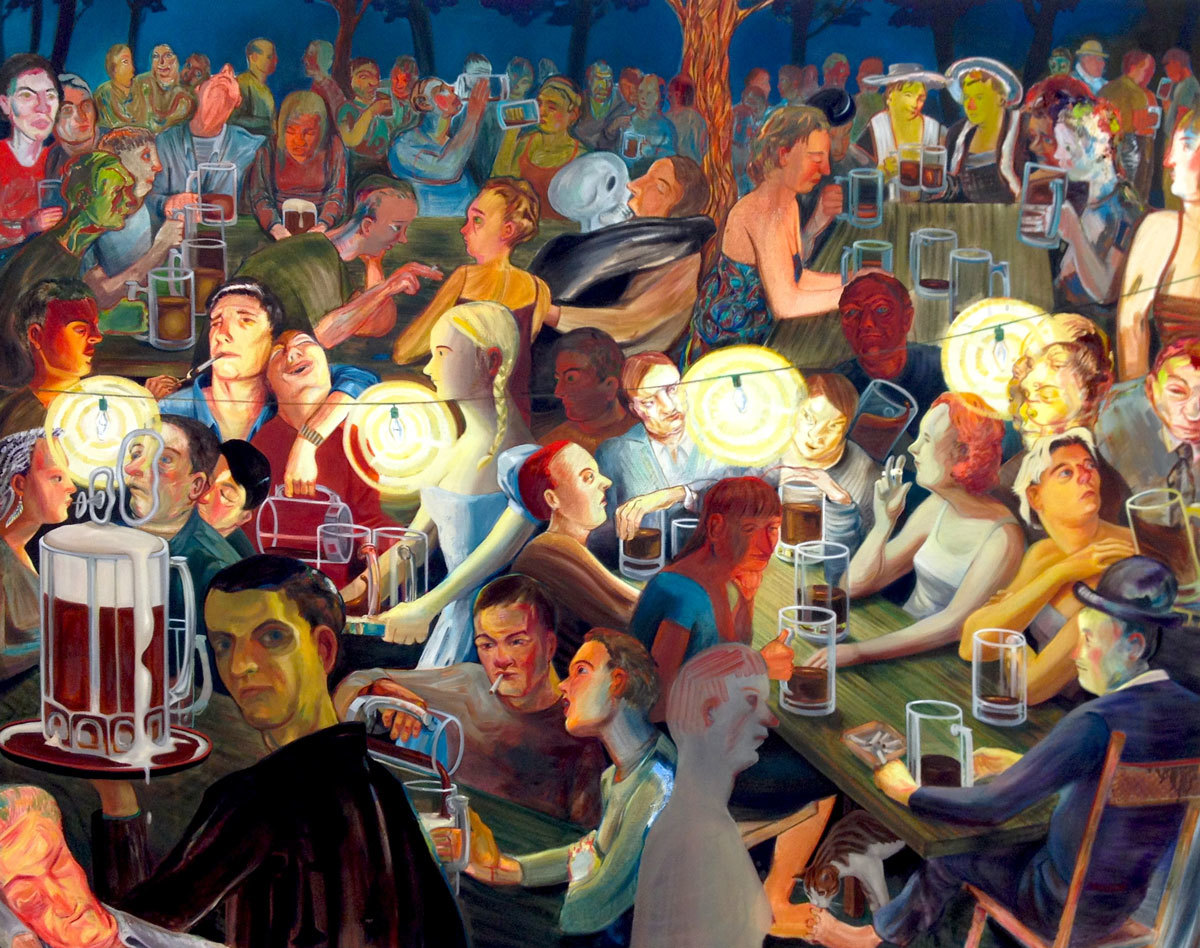

Artists Space in New York provided an almost-retrospective of Lukas Duwenhögger that chimed with more digital practices such as Spicero’s in the sense that the exhibition text provided was a story, a narrative – loosely connected to the images hanging in the space. Raven Row in London is also showing an exhibition by Duwenhögger – opening this month. Nicole Eisenman at the New Museum was riding New York’s Frieze buzz with her work, slightly uncanny and bloated figures staring out like art-historical ghosts reeking havoc on our sleek contemporary sensibilities.

Chantal Ackerman has become a firm favourite in the UK of studying artists and art historians, a cry to finally put her in her rightful place has seen symposiums bringing her into the limelight again and again. Megan Rooney’s erratic formal approach to mural making, canvas paintings and also sculpture veer between abstraction and figuration in a style that is confidently not male, and the demand for her work is growing – the artist is under 30 and having just come for her solo show at Croy Neilson in Berlin is exhibiting another solo show at Seventeen Gallery in London.

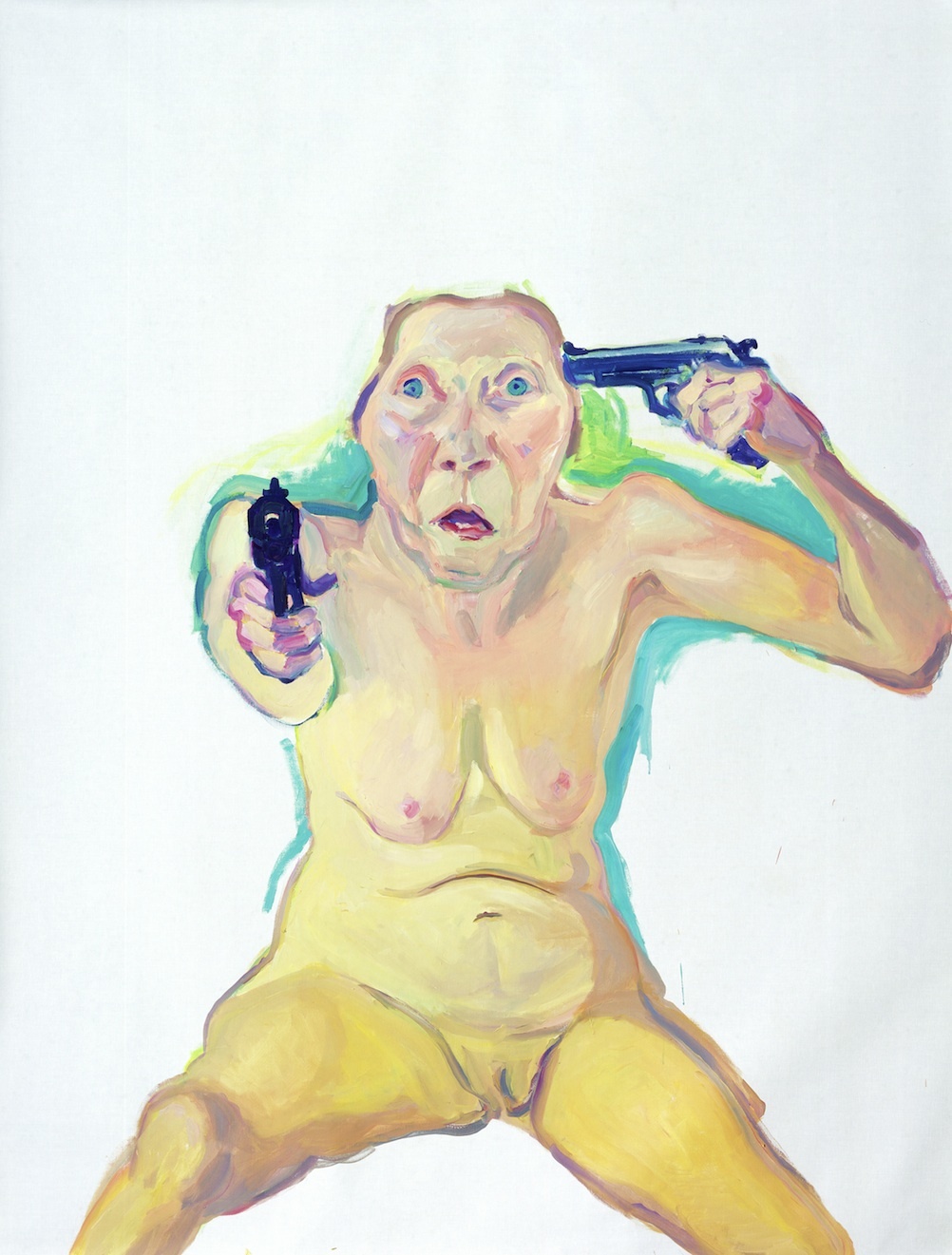

Tschabalala Self was one of the highlights of NADA NY. The artist uses her own image in various poses to make up familial and portrait style pieces – as did Maria Lassnig, whose works are on show currently at Tate Liverpool – threaded together in fabric and paint. Art critic Waldemar Januszczakdescribed Maria’s work as trying to paint how the body feels, that Tschabalala Self is challenging us to assess how identity looks.

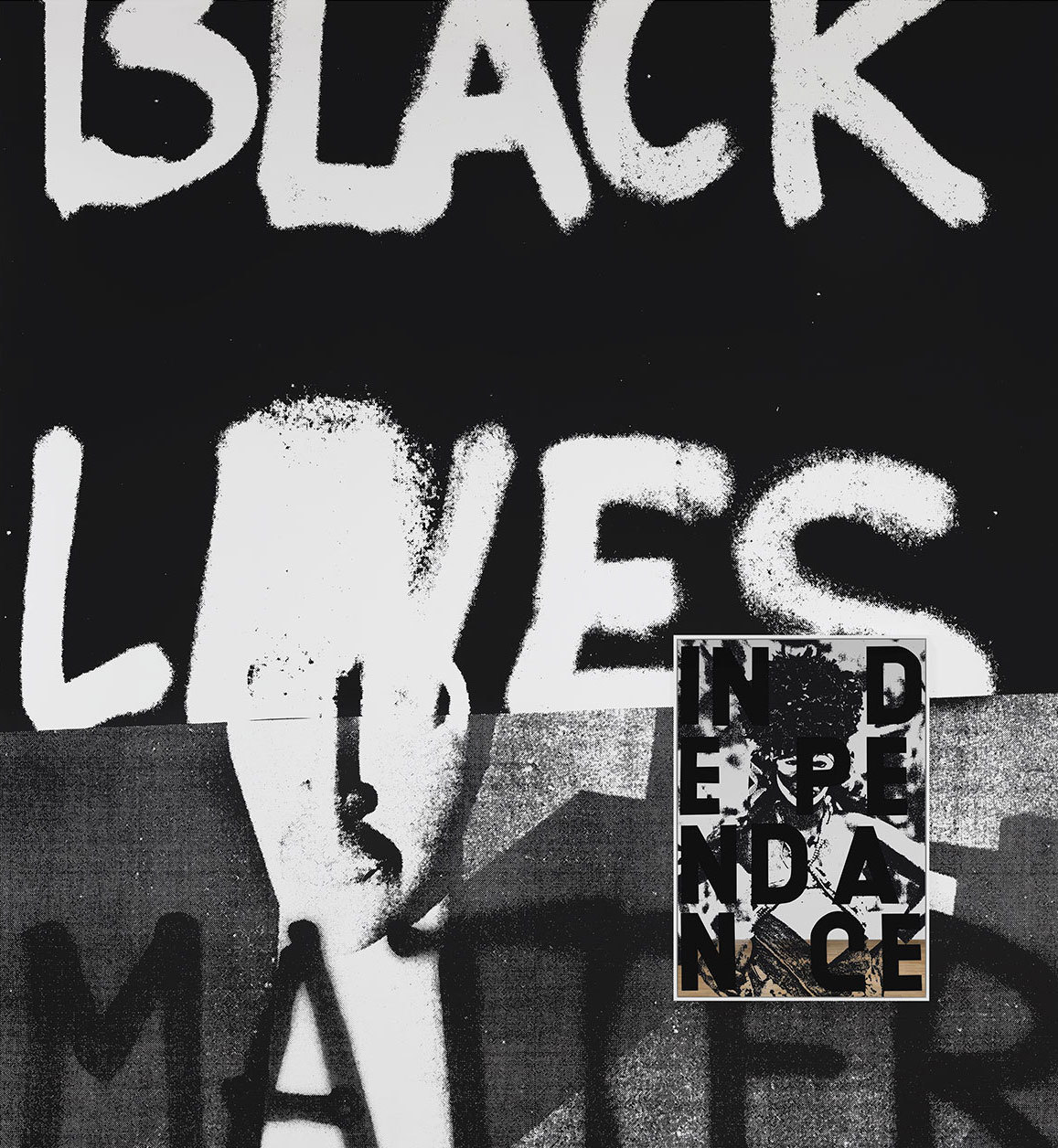

This recent explosion of figuration, or rather of art institutions and galleries desire to show figuration, does not seem so surprising, although it has appeared fast. If we take 2014 and the rise of neo-abstraction and New Cynicism as a catalyst, then a figurative response makes sense. The circulated works, the works of abstract bleached-out uniform beauty so associated with (one of) the nasty side(s) of art seemed to revel in their disassociation from the body, and were heralded by those non-body people — we know that only the rich, the white, the cis, and the male are not read through their bodies, are read as floating heads of non flesh that do not have to be ghettoised by identity, thus have no interest in speaking about it. The desire for art to have a voice suddenly meant it had to have a body, and this is important as there are more practices that speak of and have bodies in less literal ways than the painters and artists mentioned in this article… Park McArthur, Jesse Darling, Adam Pendelton, etc.

Sadly, although the trend in figuration is upon us, there are only certain terms in which it is allowed to figure. The spectre of an aesthetic or ideological sensibility that is written as the only modernism has been shown as alive and well against the hushed histories of artists and artworks where the body laid out ‘uncomfortable’ identities onto the art world. The Where is Ana Mendieta? actions at the new Tate Modern building, against Carl Andre’s brick works on display is the best current example highlighting how collections still hold power and push traditional agendas, write one sided histories, and don’t seem to take much to bodies.

Figurative painting has been taken up again as part of the battle of identity politics – the term itself is difficult, whose identity? What politics? This ambiguity chimes with tensions in struggles themselves – is visibility at any cost that helpful? As put by Liv Wynter, “Progress does not come when we are granted the right to become part of the oppressive system. Progress comes by dismantling these systems, not reinforcing them.”

What is great, and challenging, is that many of these practices divert the aesthetic motifs of art history and kick us into a remembrance of the foundational imperialism of art itself. These paintings want mess, want relationships, don’t give a shit about object oriented ontology or if the NSA is watching them, because their bodies were always publically owned objects anyway.

What they risk is whether their representation garners appropriation and fetishisation – and this risk is not taken lightly, it is taken on knowingly and deliberately. The further risk is interesting, perhaps one to be wary of — restating the compromise of visibility — the move from figuration in drawing to full on paintings reminds us that again, paintings always sell.

Credits

Text Rózsa Farkas