This article was originally published by i-D Australia

While New Zealand was relatively quiet in the early 90s, the young people, like young people everywhere, were devouring the era-defining fashion and editorials of magazines like i-D and The Face. In a pre-internet, pre-PR agency world, these were the bibles that united the like-minded spirits of a generation. And in this atmosphere, in 1993, Auckland-based journalist Barney McDonald was inspired to launch his own publication. Spurred by a desire to write the kind of stories he wanted to read, he took a literal approach to naming his new street culture title Pavement — enlisting the best Australian writers and photographers he knew.

While it already possessed the makings of a cool project, Pavement still needed someone to steer its design aesthetic and fashion content. Fatefully, art director and designer Glenn Hunt had recently returned to New Zealand after an inspiring stint in London. He immediately saw the publication’s potential and contacted Barney about working on the launch issue. Glenn went on to creatively direct every issue of the magazine that would come to reflect 90s cool in New Zealand and around the world.

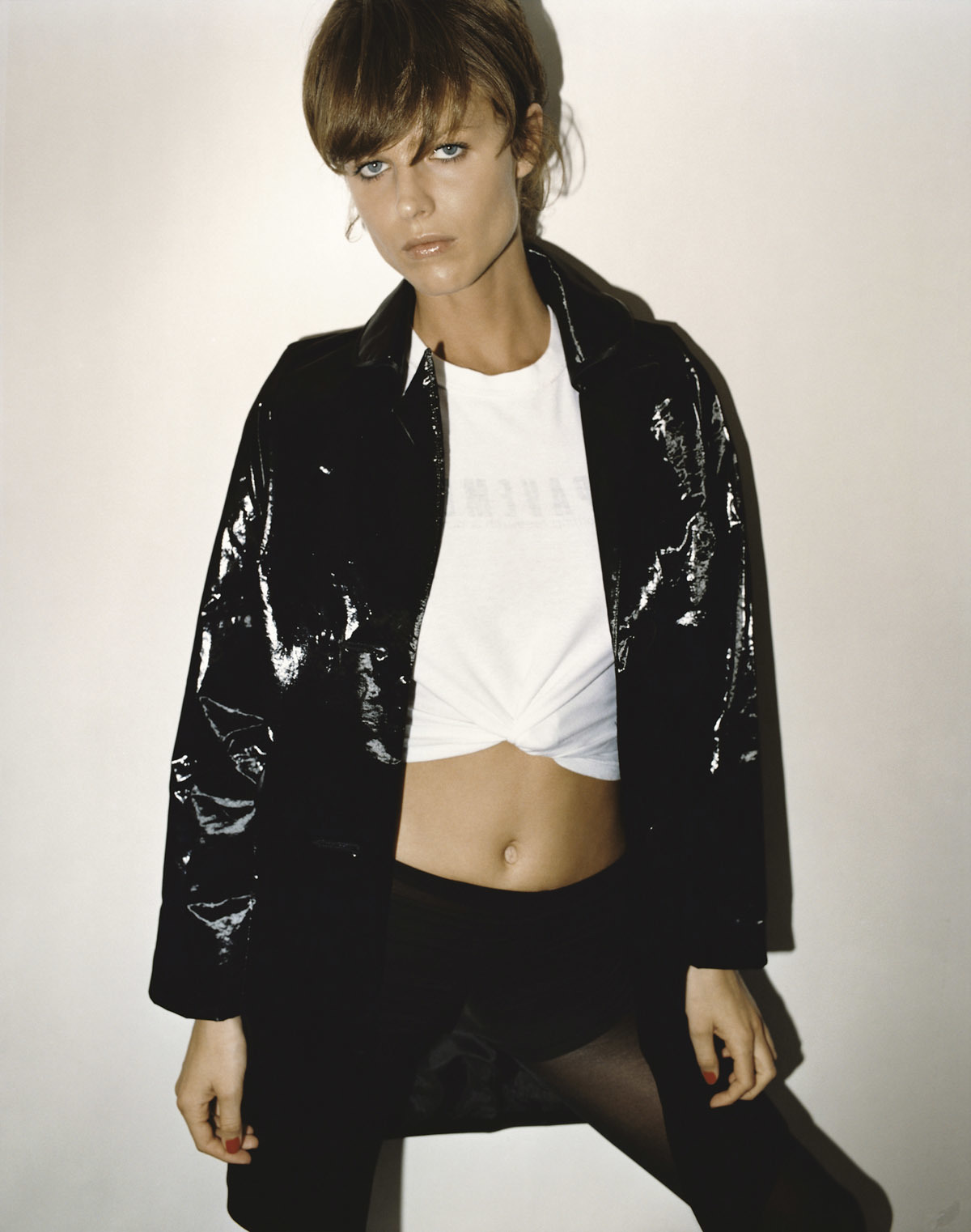

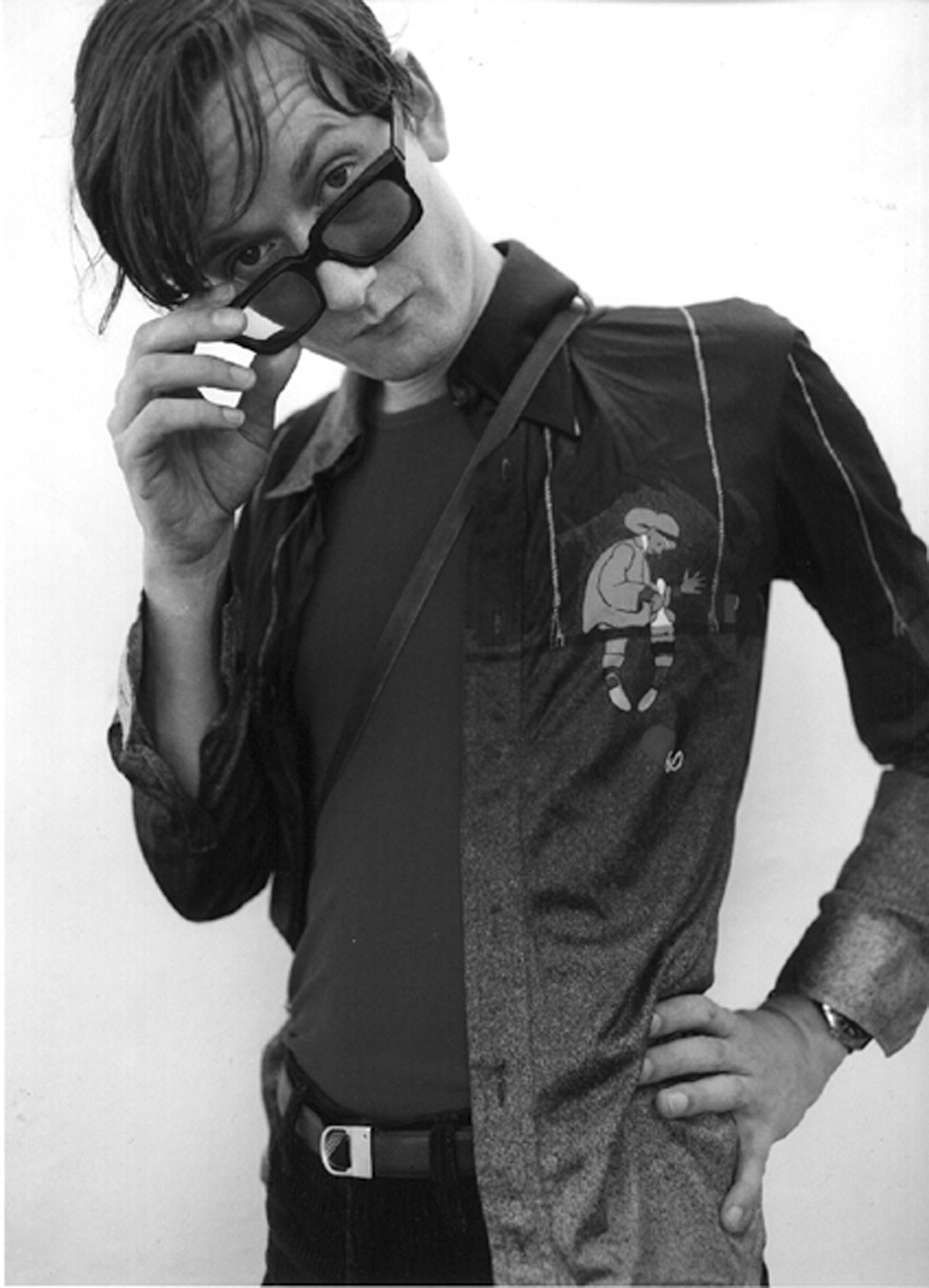

Pavement ran for 13 very busy years. In a little over a decade the team shot everyone from Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, Johnny Depp, and Leonardo DiCaprio to Cate Blanchett, Angelina Jolie, Courtney Love, and even some of the very first pictures of an emerging model named Gisele Bundchen. We spoke to Barney and Glenn about New Zealand in the 90s and peered into their impressive archives.

Can you tell us a bit about the very early days of Pavement.

Barney: I got the ball rolling and Glenn came to see me about designing the mag. We’d both been raised on a healthy diet of international mags and Kiwi titles like Rip It Up and Cha-Cha. So we clicked right away.

Glenn: When I came along, even though the first issue was only 64 pages and all black and white, with no fashion shoots, Barney had some interesting, well-written content. I instantly sensed the potential of what we could achieve.

What was it like in NZ at the time?

Barney: NZ felt like it had the potential to be more international in its creative outlook, but was still hemmed in by an inhibiting parochial nature. But the culture accelerated in the 90s. Key local fashion designers were progressively looking overseas for new markets. Peter Jackson made Heavenly Creatures, then The Frighteners, paving the way for his Lord of the Rings trilogy. OMC released the one-hit-wonder How Bizarre and topped numerous international charts. Drum and bass hit the clubs and raves. It was all go! It energized us. Hopefully we energized others.

Glenn: We didn’t need to do market research; we were a part of the target market. We had access to a great pool of contributors and talent that also needed a platform. We trusted our instinct and never doubted that we’d succeed in providing that.

You’ve said that Pavement was you bringing the world to NZ and taking NZ to the world.

Barney: We quickly developed a network of contributors outside NZ who could shoot stories for us, whether music, film, or fashion. Some of them were Kiwis. Derek Henderson, Regan Cameron, Max Doyle, to name a few, plus several Kiwi photographers continued to shoot for Pavement when they ventured overseas. As Pavement gained currency, plenty of foreign contributors came on board because they enjoyed what we were doing and the creative freedom we fostered. Our philosophy was: if it’s worth doing a story on, it’s worth doing our own pictures for. No original pictures meant no story, mostly.

What was Pavement’s aesthetic and how did you keep it consistent?

Glenn: It was the single-minded thing that drove me — to despair sometimes! Especially in the early days when there weren’t enough pages to do what I wanted and too many bloody words! I loved what Barney was producing and always felt it was my duty to bring those words to life in the best way I could. Barney and I both loved and appreciated photography and it became one of the strong points of the magazine.

Do you have a favorite story, shoot or editorial, something that has really stuck with you?

Barney: There are still a couple of covers that make me cringe. But mistakes help color the palate. We evolved one step at a time, but the genesis of what we wanted to do was there from the outset.

Glenn: I always got a special thrill from the supermodel covers. It just made me really proud to see the same face on the front of Pavement as on Italian Vogue, but shot in our style. My most memorable shoots were those where we took visiting bands, Placebo or Elastica, out to the West Coast beaches for the day to shoot them. There’s a great shot of Placebo’s Brian Molko standing on the rocks at Piha getting totally wasted by a huge freak wave.

Barney: We were always brawling over how much space text should get. One night at the office Glenn was having a go at me over the length of a story. I picked up the first thing that came to hand — a reasonably large Oxford Pocket Dictionary, as it happens — and threw it at his head. It was a good throw! He stormed off to his office, but a minute later we were both cackling with laughter.

We’ve heard about the parties, can you tell us more about them?

Barney: We had MASSIVE parties. We even threw Australian Fashion Week parties at Q-bar on Oxford Street. I remember Laurence Fishburne turned up because, little did we know, he was shooting the first Matrix movie in Sydney at the time. He was a nice guy, very tall.

Glenn: Sometimes we’d throw after-parties for visiting bands like Massive Attack, Marilyn Manson, or Interpol. One of my highlights was when Johnny Rotten turned up to a Pavement birthday party, as obnoxious as ever. When one of the photographers offered to light his cigarette, his response was, ‘Fuck off, you peasant!’

What changed about the cultural landscape in the time you were doing Pavement?

Barney: PR people started sticking their beaks into everything. Fashion weeks took up too much of a designer’s time and marketing budget. Music changed fundamentally as well. Digital took over, as it did for photography. In the 90s, all the pictures we published were shot on film. And it was fun pouring over proof sheets and prints. Digital was the seismic shift.

Glenn: I really noticed a considerable shift from the early 00s. In the 90s, it felt like we were truly part of a continuously evolving alternative creative scene where paradigms were constantly shifting and always inspiring. You could still be original and a sense of aesthetics and even history were important factors in informing and motivating what one did. Ironically, it was alternative media like us that helped propel youth culture into the mass market.

What eventually led to its closure?

Glenn: I was sick of getting the dictionary thrown at me!

Credits

Text Briony Wright