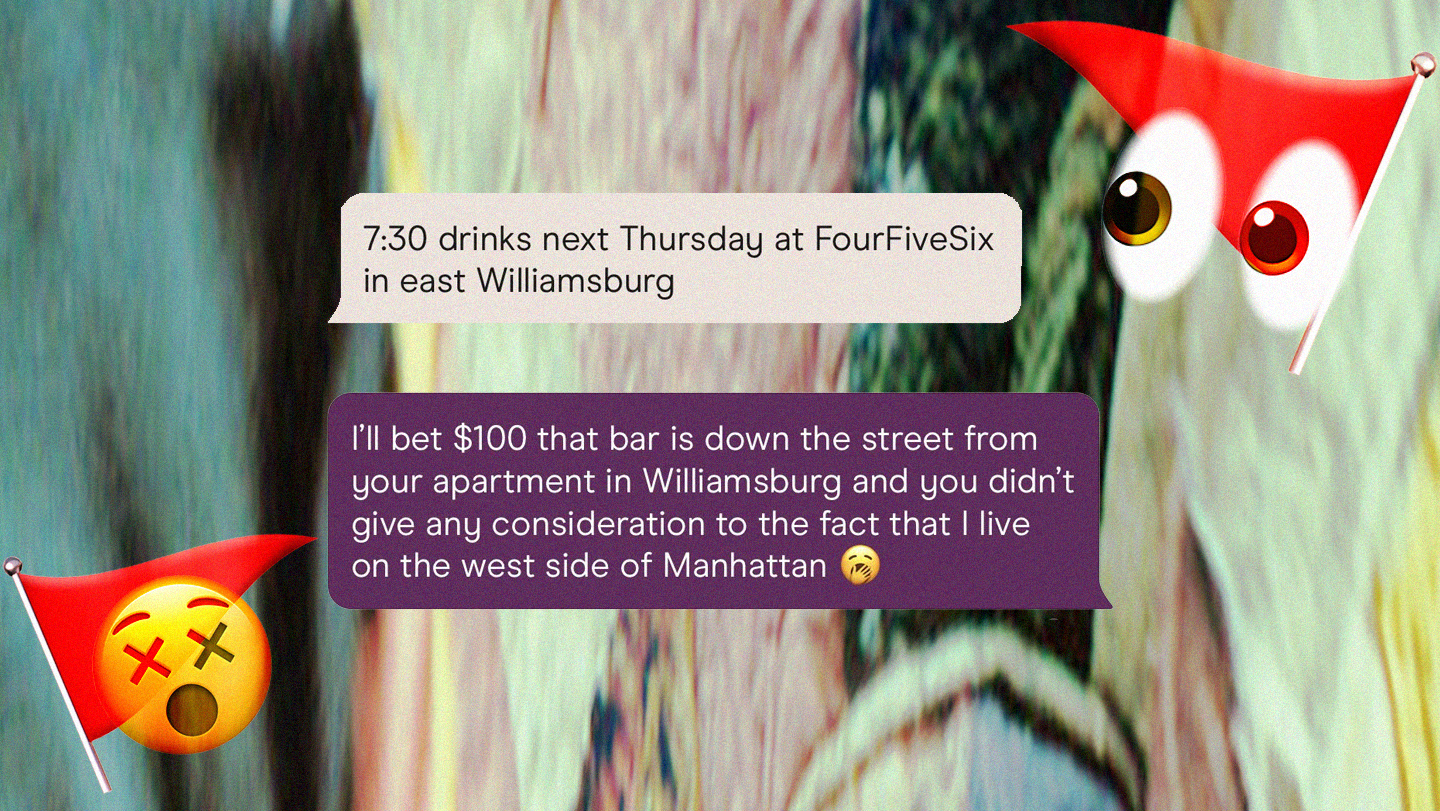

Earlier this month, Clarke Peoples posted to Twitter a screenshot of a conversation with a man over Hinge which sparked a heated debate. On her Hinge profile, Clarke wrote that she liked it when a guy opened with a “place and a time” to meet, to which the man responded with a time and the address of a bar.

In her reply, Clark chastised the man for inviting her to a bar in Brooklyn, considering she lives in west Manhattan. “He really thought he ate that,” Clarke wrote in the tweet. “F for effort in asking me to travel an hour to have a drink with you at a place 2 blocks from your home.”

The tweet elicited mixed responses from those who felt that the man in question had done nothing wrong, and others who agreed with Clarke, calling his actions a red flag. But arguably more interesting than whether the man was right, wrong or just lazy is the wider phenomenon it pointed to. Namely, dating vigilantism, which is seeing people use technology to surveil each other’s behaviour, while transforming our personal and romantic lives into a public spectacle.

The internet is awash with screenshots like Clarke’s of private conversations and dating profiles from apps like Hinge, Tinder and Grindr. Like Clark’s tweet, some of these are intended to drag people for dating faux pas, while others expose men for being a “community dick”, or for more serious crimes, like sexual assault. This kind of dating vigilantism has the potential to keep people safe, but it also raises ethical questions: in what instances is it OK to share private conversations or images without someone’s consent? And where is the line between protecting others and gossiping?

This kind of content is increasingly being shared to “Are We Dating The Same Guy” Facebook groups, which allow women to vet the men they’re talking to before meeting up with them in person. They’re comparable to whisper networks: the informal chains of communication used to pass on information about alleged sexual harassers or abusers which grew in popularity during the #MeToo era. There are countless examples of women who’ve been alerted to dangerous and violent men thanks to these groups, or, on the other end of the spectrum, been made aware of the fact that the guy they are seeing is talking to other people. (With research showing that 42% of people using the dating app Tinder already have a partner, it’s no wonder these groups boast tens of thousands of members).

Sharing screenshots to Are We Dating The Same Guy groups might be seen as a discrete or safer option compared to airing our grievances in more public online spaces. This is true to some extent, given that most Are We Dating The Same Guy groups have rules in place, such as “[Don’t] speculate on posts about men you don’t know” and “Don’t make comments to make fun of men”. Still, there is an influx of posts criticising men for being a bit boring, bad conversationalists and other ‘crimes’ which some may not consider crimes at all. As these groups grow, so too does the scale of abuse, harassment and doxxing faced by the people being posted about. And often, the punishment outweighs the crime.

The public shaming and reputation ruining of people we believe to have wronged us has become a bloodsport. Last year, when women shared their experiences of being lovebombed, strung along and ghosted by a New York City-based designer known as ‘West Elm Caleb’, it sparked an online mob. The outrage spilled onto Twitter, and then tabloids, which published his full name. Clearly, West Elm Caleb’s actions did not warrant such a brutal pile on. In the public’s imagination, he became the living embodiment of everything wrong with online dating culture – but taking him down was never going to be the answer to this.

It’s not that West Elm Caleb, or even the man in Clarke’s tweet, don’t deserve to be held accountable to some extent. But the motivation of the people sharing this kind of content isn’t always clear. Taken in good faith, turning questionable or downright terrible behaviour into content is a way to warn people about ‘bad men’, or to educate others about dating etiquette or how to spot red flags. In reality, though, it’s at least in part driven by a desire for viral attention and as a way to validate feelings of hurt we’ve all experienced on some level through likes and retweets.

Often this fails to consider the circumstances of the person whose information or private conversation is being shared. “We don’t always know if that is a true version of events, and we don’t know the other side of it,” says Miranda Christopher, a relationship and sex therapist. “We might be going vigilante on somebody who’s actually quite vulnerable.”

This isn’t just about protecting men, but also asking what kind of dating landscape we want for ourselves. When it comes to Are We Dating The Same Guy groups, Veronica La Marche, a Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Relationship Scientist, is concerned about the potential for this kind of vigilantism to heighten anxiety and distrust around dating. “If you’re engaging in dating forums that only focus on the negative things that can happen in a dating context, you may be inclined to believe that that’s the highest likelihood of what will happen if you go out on a date,” says Veronica, who advises checking these groups in moderation.

Miranda Christopher makes a similar point: “The danger is you enter a situation from the position of ‘people are bad’,” she says, “and that when you start to date somebody or even talk to them online, you’re already looking out for the ‘red flags’.” This isn’t helped by the spread of pathologising dating terms, such as terms like ‘love bombing’, ‘ghosting’ and ‘toxic’ – in other words, the ‘crimes’ we hold men accountable for.

Veronica points out that the proliferation of such language could be priming people to interpret behaviours in certain ways. “It can make us see things in black and white, as opposed to creating space for more nuance, or a less intense interpretation of these behaviours.” These buzzwords can help us to recognise harmful behaviour, but also have the potential to be reductive and can limit our empathy.

We should be able to speak about red flags and troubling behaviour, and hope for some kind of consequences for perpetrators. But it’s also worth questioning whether the publicly shaming of individuals is always justified, and what it actually achieves beyond providing viral fodder.