Last night, a friend texted me: “How are you feeling? I’ve been seeing your finstas.”

While my real Instagram showcases a never-wavering aesthetic of candy-colored photos of me and my city life, my “fake Instagram,” or finsta, is a vortex of moody selfies, memes, and life updates only on view for my closest friends. It’s always changing and portraying the ups-and-downs of my real life, like a constantly-updated, digital diary – whereas my actual Instagram is a highly curated, careful presentation of how I want to be seen.

I post on my real account a few times a month, and on my finsta a few times per day (or even hourly). Nearly all my friends have finstas, and have similar posting habits. Scrolling through my real account is a blur of seemingly perfect lives, while the same friends will be on their finstas posting snapshots of heartbreak.

Speaking to social media professionals and Gen Z kids from four continents and twelve cities, I tried to get to the heart of our digital dichotomy of “fake” and “real” online identity.

Last summer a study found that Instagram was the worst form of social media for your mental health. The image-centric app was linked to high levels of anxiety and depression — and this study comes as a surprise to literally no one.

Adam Alter, NYU Professor and author of Irreversible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked, explains: “People curate their feeds to show only the best 1% of their lives to others, giving the impression that their lives are better and more exciting than they really are. This isn’t true to the same extent for Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter, which have a different purpose and include a more varied range of content.”

Klyn, a psychology student from Chicago, agrees. “If people looked at my finsta, they would never be able to guess I’m depressed.” Her feed stitches together sun-soaked snaps with professional photo shoots and party pictures — no detectable sign of mental health struggles. She hopes we move “towards a society where people feel comfortable being vulnerable” — but for now Klyn, and so many others, only have finsta as an online space to be vulnerable.

However, beyond being a platform to embrace vulnerability, finsta is also a way to reach all your close friends, all at once. “I have my friends from prep school, I have my friends back home from Ghana, I have my friends from my time in Paris,” says Nhyira, a student at Georgetown. With all these international friends, Nhyira told me about the cultural differences in the way we use finsta: “In America, kids typically use finsta to vent and post ridiculous photos. Back home it’s a platform for people to post their quote-on-quote inappropriate photos.” In Accra, a very conservative place, finsta becomes a place for self-expression in the way a “real” account can’t. Sophia, from Vietnam, elaborates that “American finstas tend to be unapologetically self-involved and have a lot more emotional baggage in comparison to my international friends, who are less serious, and probably post more drunk photos.”

On finsta, you undeniably can be whoever you want to be. John, a New York-based photographer, came out on his finsta. “I only wanted my close friends to know,” he says, shrugging.

Meanwhile in the vaguely-cultish world of sororities, finstas can be a necessary reprieve from how intensely the girls judge each others’ ‘rinstas’. “Instagram plays a huge, huge role,” says Sarah, from the University of Arizona. “You look at the number of followers on each person’s account and make harsh snap judgments. It’s everything.” Sarah unashamedly plays the game too — sometimes she gets all dressed up to take pictures, only to immediately take out her extensions and go back to bed. “Social media is an art form, and you can fool everyone.”

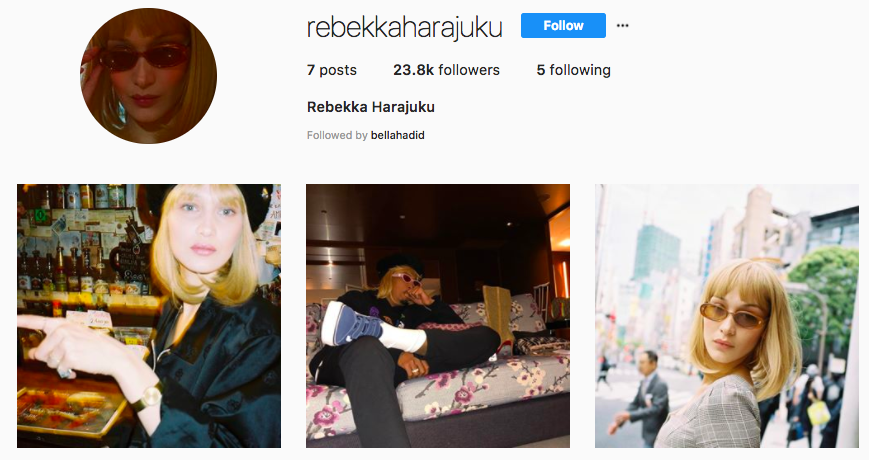

Another one of my friends, Vienna, is someone who might be referred to as an “influencer,” with a rinsta following that’s 70 times that of her finsta. For her, beyond using a finsta as a “visual diary,” she uses it as a way to separate her “physical and emotional self.” Parisian fine arts student Viona echoes that sentiment, and talks about how DM’ing anddigital romance play into that concept: “On instagram, you’re hiding physical impressions and hiding dimensions of yourself — it’s impossible not to. Meeting people in real life has become a fantasy for our generation.”

After hearing all of these perspectives, I seriously wondered whether it would be best for everyone if we combined our physical and emotional selves and did away with finstas entirely. What if we were all just “real” on our real accounts, all the time?

I turned to my friend Lili from Toronto to ask why she uses her real account in the way most people use a finsta — regularly posting about everything from drug use to breakdowns to insomnia. “I do want my main account to be a finsta,” she says. By making the simple yet complex choice to not filter herself online, she’s alleviating her social media anxiety. “A lot of my followers respond to posts saying that they relate — because we’re all going through the same thing.” She adds, “Finstas are definitely a coping mechanism, and I don’t know if it’s a healthy one. Most coping mechanisms aren’t.”

So, should we all be like Lili? By so intensely shaping our online identities, are we actually losing control of our identities? Are we becoming digital brands, rather than fully-dimensional people?

Perhaps a way to detonate these dilemmas is to mass-delete our finstas. Perhaps if we did, we’d collectively heighten mental health awareness (an issue Instagram does acknowledge and plan to take on). Perhaps our relationships with ourselves and each other would grow stronger. However, on another level, perhaps it’s time to realize it’s impossible to be ‘real’ online. We can’t truly ever represent our heartbreak or pain or love through shifting pixels on a screen. We have no way to tell how long someone took to craft a confessional caption, or how many minutes someone spent Facetuning a selfie. We can’t know if someone’s manipulating their image, or if they’re even aware that they’re doing so. We’ll never be able to verifiably know if someone’s lying online.

Social media is an art form — and in 2018, whether we like it or not, we’ve all become artists.