The day I picked up a skateboard for the first time was probably the happiest day of my life. I was 26, and the piece of battered maple wood decorated with acid-colored octopus was donated by my boyfriend. At 33, he could still do most of the tricks he learned as a teenager. We went to a small patch of concrete by a pink tower block glowing against the dark grey London sky. My awkward beginner’s exercises didn’t give me much wind in the hair but they did give me, apart from a couple of bruises, something unforgettable — a sense of belonging to the great urban myth of youth and freedom, to the ephemeral gang of beautiful renegades who have carelessly slid through life since the 70s.

Learning to skate when you’re well out of your adolescence is not uncommon. Cult filmmaker Larry Clark, who was among the artists to define the iconic look of the skate scene in 90s, learned skating at the end of his forties, just before making Kids. Although his case is rather exceptional, the age of today’s urban skaters is definitely more varied than before: it’s not just a pastime for bored suburban kids but a huge part of fashion, contemporary visual culture and urban environment.

In the past year London’s cityscape was marked with two spots crucial for the state of contemporary skateboarding. In October 2014, Rom Skatepark in East London was awarded heritage status. Built in 78, it was the first skatepark in Europe to have its concrete curves protected from decay and redevelopment. As a consequence you now have to pay for entrance and wear a helmet (lame) but this might be the price of institutionalization. Just a month before, in September 2014, Southbank Skatepark, a much loved graffiti-covered cave on the bank of the Thames, was saved from redevelopment after a long battle of arguments and petitions. Both indicate that skateboarding is now acknowledged as part of a city’s cultural lifeblood, even by those who probably have no clue about Larry Clark, Palace or Dog Town.

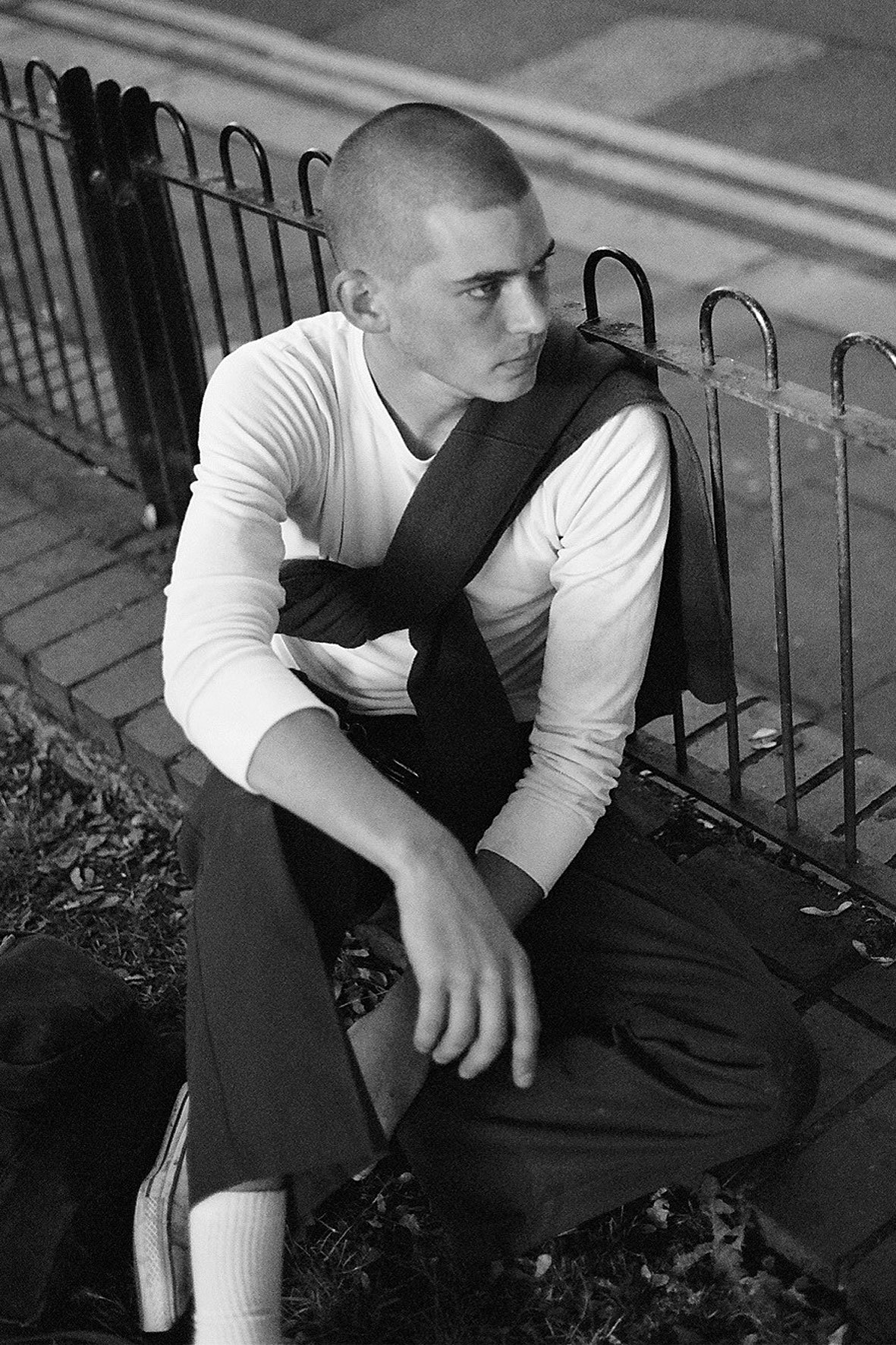

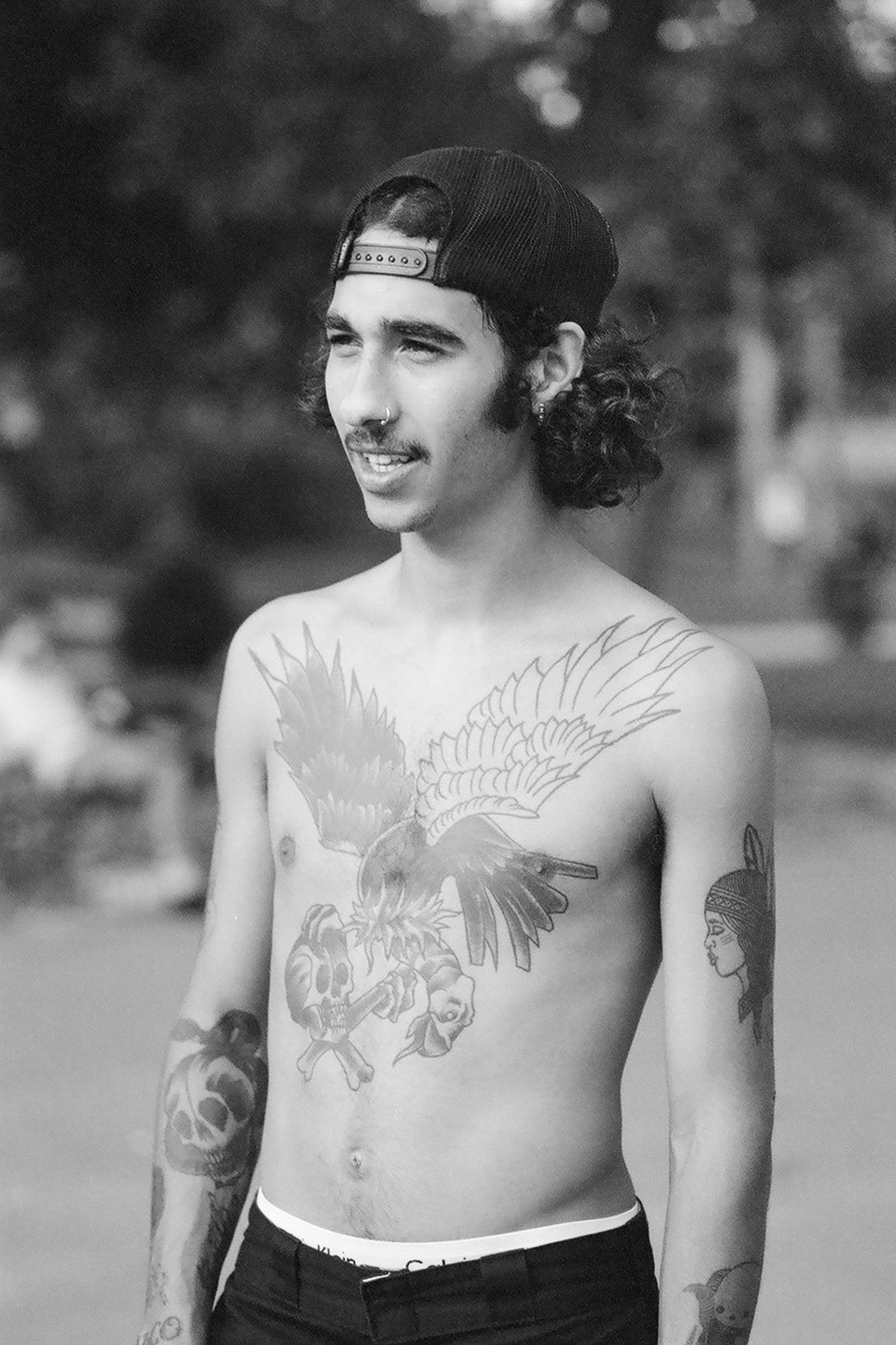

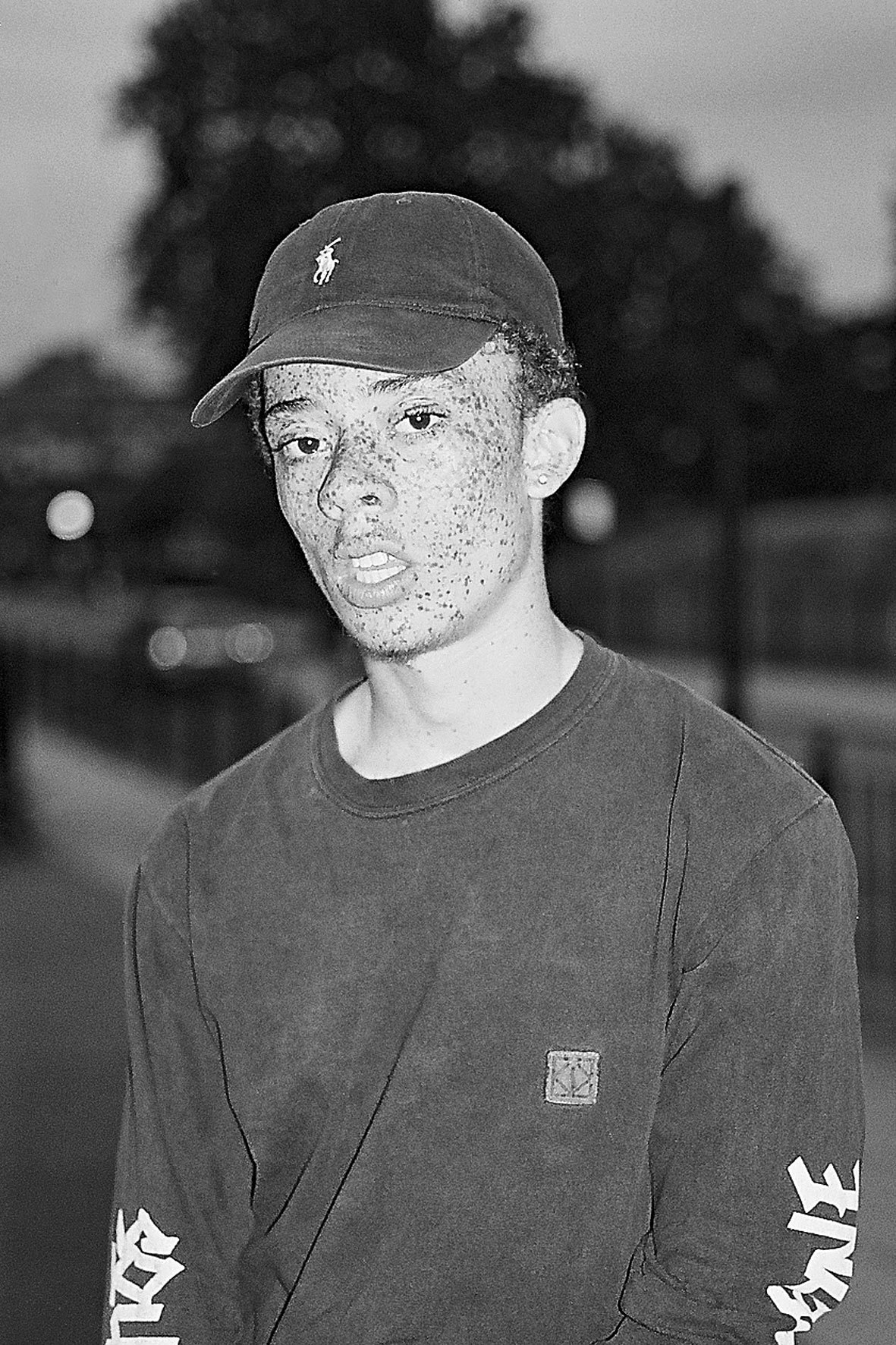

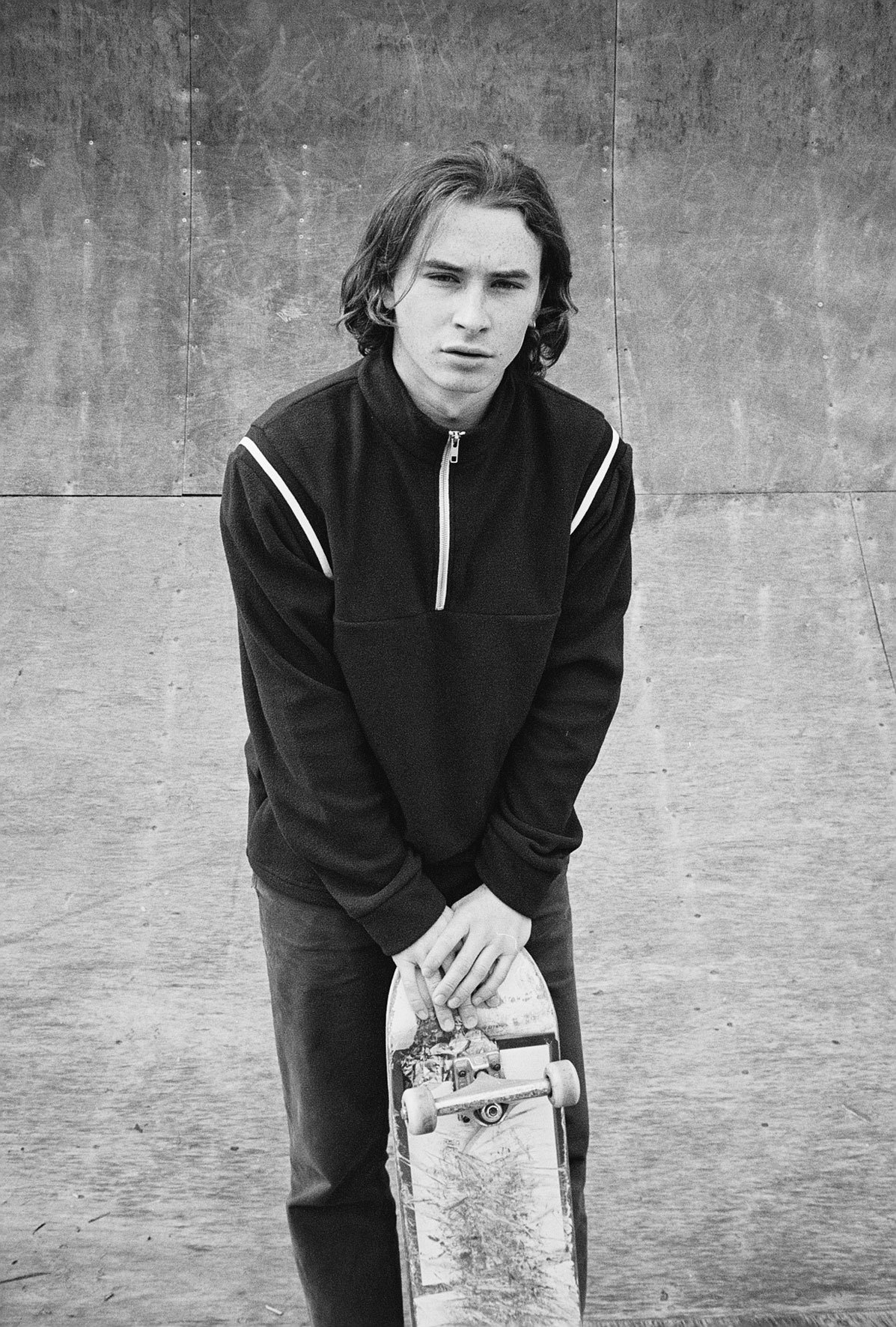

24-year-old photographer Ian Kenneth Bird started photographing London skaters about a year ago. He’s been skating for 10 years, but it was the first time he’d decided to combine his two passions. Captured in black and white around skateparks and East London streets, the boys in his photos are fellow skaters and old friends. Despite capturing such messy, noisy and at times bloody activity, his shots are strangely tranquil: smiles frozen in time and skateboards resting on walls. The photos could have been taken yesterday or five years ago – it reflects the timelessness of skateboarding Ian believes in. “I don’t think popularity or youth have anything to do with it – skateboarding will always be there – trends in fashion and culture may come and go but this isn’t anything that hasn’t happened before”, he says.

Skateboarding’s rise to the timeless status could not have happened without photography. Skating we know today was shaped by the invention of the polyurethane wheels in 1972 and Craig Stacyk’s photographs of the legendary skater team Z-boys in Santa Monica, California. A team of sun-kissed rebels riding streets as if they were ocean waves, searching through backyards for drained swimming pools to practice in. The 70s saw the opening of the first skateparks, modeled after these swimming pools, and the first big skateboarding competitions. In the late 90s skateboarding had its second wave of mainstream fame – with hip hop, baggy jeans, grunge, and of course Clark’s Kids, which turned 20 this year.

Following contemporary 90s obsession, the skater T-shirt is back, only the brands are different: London-based Palace with its VHS skate videos and grime; iconic streetwear brand Supreme; LA-bred Bianca Chandon founded by the second generation pro skater Alex Olsen; Gosha Rubchinskiy and his crew of post-Soviet skaters. With Raf Simons’ favorite stylist Olivier Rizzo incorporating Thrasher T-shirts in his shoots, and Larry Clark collaborating with J.W. Anderson, skaters are definitely the fashion world’s recent crushes.

One could argue, however, that this has little to do with the real thing: the moment when it’s just you and the board, the thrill and fear of looking down the pool, the pain of falling and scratch of the rough pavement. Skating has been a commercial venture for several decades, and has periodically gone in and out of fashion, but somehow it resisted the corrupting effect of all the industries around it. Probably because there is nothing more real than falling ten times in a row before managing to accomplish a trick: this degree of hope and failure is only available to us in childhood. But there are other, more cultural reasons too.

Firstly, skateboarding is transnational — a common language which unites kids from Afghanistan to Russia to the US. Short film Wasteland directed by Nadia Bedhzanova is an interesting glimpse into this unity powered by boards and group chats.

Secondly, skateboarding is a rare way to transform an urban environment. American photographer Rich Gilligan produced a whole book on the evidence of skaters’ communal effort, documenting D.I.Y skateparks around the world, often built illegally by skaters in hidden parts of the city. They’re transient monuments to the subculture, which could be knocked down at any time.

But the key reason is political. Skateboarding has always attracted the outsiders: it’s free and once you’ve invested in the board, you can do it pretty much anywhere. A new strip of asphalt or the concrete curves of a brutalist building — no one will take it away from you, although you might avoid to play cat and mouse with overzealous security guards. When you’re a kid freedom is an instinct, but when you’re an adult it’s a conscious choice.

In today’s London it’s easy to feel like an outsider: struggling with paying rent or repaying tuition fees as new shiny developments get erected all around us. We live under a Conservative government which doesn’t represent the interests of the young and with no improvement in the foreseeable future. Is skateboarding going through a renaissance because we’re dreaming about taking back the streets of our city?

Credits

Text Anastasiia Fedorova

Photography Ian Kenneth Bird