From the sidelines of sports fields to the runways of Paris, the hooded sweatshirt is one of our most iconic wardrobe staples. Its design has barely changed in almost a century, yet it’s been adopted by every generation as an emblem for outsider-ness and subcultural affiliation. The hoodie has been a blank canvas for punk, hip-hop, and skater cultures; it’s had brands and bands splashed across it. The hoodie is a vivid symbol for music, art, and rebellion. The hoodie even sparked political debates, become code for urban decay, and been banned from some public spaces.

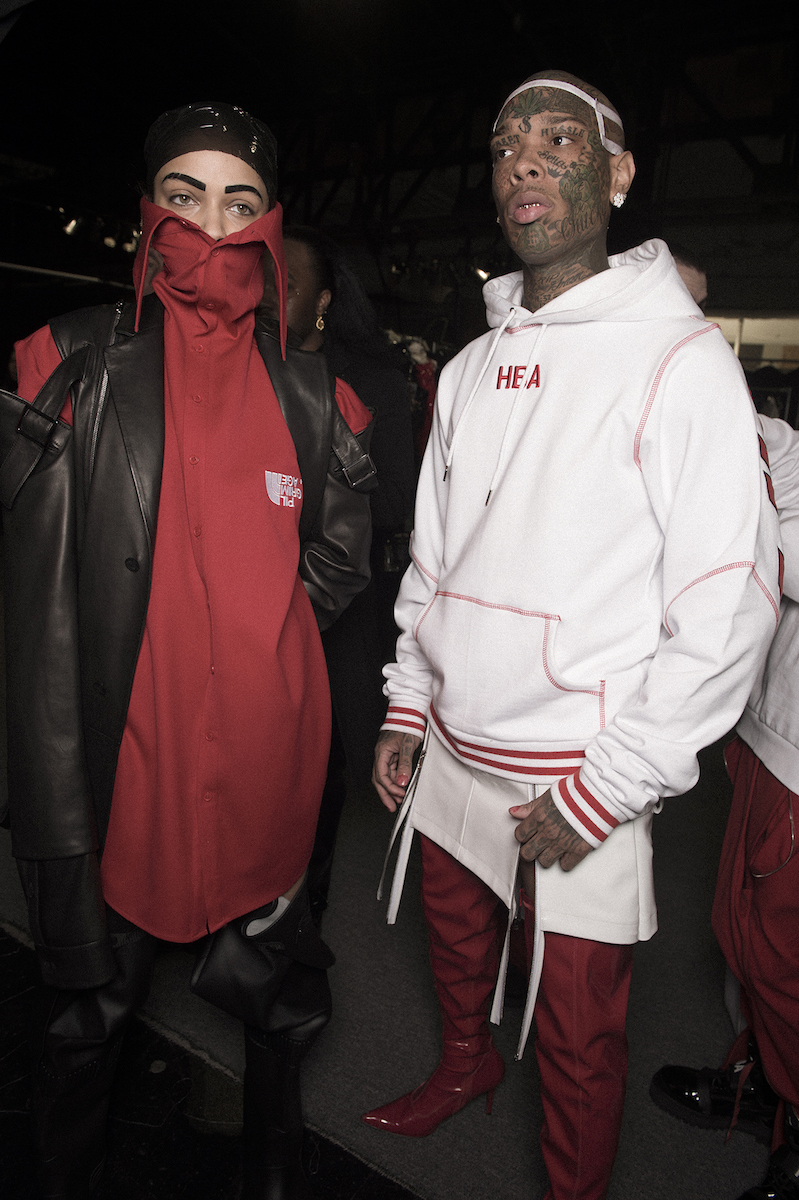

The fashion industry has always had one eye on creative and flamboyant styles rising out of subcultural scenes, and designers have a knack for tapping into them as an easy means of capturing the spirit of the times we live in. Streetwear influences in high-fashion can be seen as far back as the collections of Yves Saint Laurent, who regularly drew inspiration from the streets of Paris and the women around him to create a new vision of strong feminine sexuality. On the other hand, Raf Simons has tapped into the tribalism of the outsiders who live on the edges of mainstream culture to craft a new way of dressing for men, and leveled an entirely new symbiosis between fashion and street when he launched his label in 1995. His seminal spring/summer 02 collection, “Woe onto those who spit on the fear generation… The wind will blow it back,” used streetwear — specifically the hoodie — to confront wider political issues. Models strode down the runway decked out in primary colors, masks, and clothes daubed in visceral slogans while holding flares. “We are ready and willing to ignite, just born too late,” the hoodies read.

Raf’s influence can be felt in the latest wave of hoodie advocates like Gosha Rubchinskiy and Vetements, brands who have achieved incredible success by capturing the spirit of the youth movements that gave the hoodie its symbolic status, and repackaging that ethos. Rubchinskiy explores adolescent life in Russia through the lens of Moscow’s skate scene, culminating in sportswear collections that sell-out almost instantly. Vetements references cult skate magazine Thrasher, deconstructing its signature flame logo for highly coveted hoodies worn by A-listers such as Rihanna. In a recent interview with The New York Times, Vetements’ Demna Gvasalia explains the current appeal of the hoodie: “When you put [a hoodie] on, with the hood … the whole thing moves up. It gives you that attitude.” The hoodie he says is “a very complex garment.” Few thing manage to imply so much, so effortlessly.

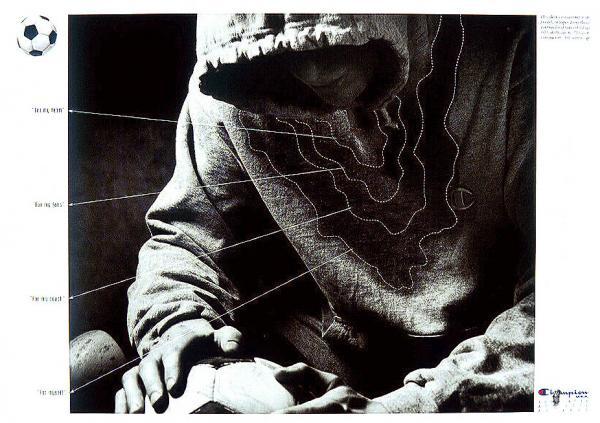

The hoodie’s history stretches all the way back to the 30s, in Rochester, New York. Brothers Abraham and William Feinbloom were at the helm of a sweater mill manufacturing sports apparel for colleges across the US, a company that would eventually become known as Champion (recently referenced by Vetements). The hoodie was initially developed as protective wear: “In those early days Champion wanted to provide a garment that would keep athletes warm before and after training,” European Managing Director and Champion spokesperson, Christopher Haggerty, explained. “It was known as the ‘side-line’ sweatshirt, as it was used by athletes who were sitting on the side line of say a football field on the subs bench.”

The Feinblooms took the crewneck and introduced elastic cuffs and waistbands to the existing design. The aim was to create a garment that trapped body heat, so the addition of the hood came as the next logical step. This became the hoodie as we know it (only back then, the hood was completely detachable). During the 50s and 60s, it gained popularity among college students as casual wear, particularly as jocks would give their track gear to their girlfriends to wear. Though primarily sportswear, the hoodie’s high functionality led to its use in the US Military Academy and as work wear by employees at cold-storage houses. According to Haggerty, construction workers in New York also adopted the Champion hoodie to protect themselves from the elements while working outside in the city during cold NYC winters.

In the 70s, hip-hop culture emerged in the Bronx, unifying rap music, turntablism, graffiti, and b-boying. In an interview for Rolling Stone magazine, early graffiti pioneer Eric “Deal” Felisbret recalls that in the context of the street, “the people that wore hoodies were all people who were sort of looked up to.” Valued for their skilled gymnastic step-work and improvised athleticism, break-dancers needed clothes they could move in and the hoodie became part of the go-to uniform. Likewise, it offered graffiti artists an inexpensive, accessible, and practical (and cool, of course) way to conceal their identities while they painted train cars and subway stations.

Simultaneously, skate culture was developing on the other side of America. Before the first skateparks were built, early skaters had to trespass to find decent spots to skate. Like graffiti artists, they shared a spirit of rebellion and the hood was pulled up to mask the skaters’ identities as they snuck into car parks, reservoirs, or empty pools. Southern California skaters gravitated towards Los Angeles’ thriving punk and hardcore scene, which emerged in a nihilistic wave during the late 70s and early 80s. Band hoodies became integral to the scene’s style. Groups like Black Flag explored themes of social isolation and poverty, which resonated with the way skaters rejected mainstream culture and brought the two subversive communities of outsiders together. The hoodie became interwoven with youth culture, but it was only when hip-hop went mainstream that it entered the fashion lexicon.

Champion became synonymous with hip-hop style; its logo was like a badge of honor on the scene. In a podcast for SHOWStudio, fashion journalist Gary Barnett cites that it was in the 80s “when the hoodie [ceased] to be an athletic item and become a real fashion statement.” Brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren did acknowledge the community, taking note of street style and reintroducing the hoodie as preppy college wear.

Hoodies also began to make cameos on the runway: Vivienne Westwood’s fall/winter 82 Buffalo Girls collection featured hoodies, and her fall/winter 83 Witches collection was inspired by a trip to New York where she met Keith Haring and paid tribute to his work and hip-hop styling. Her then husband (and former manager of The Sex Pistols) Malcolm Maclaren took it even further, releasing a hip-hop single. The pair — alongside The Clash, who were also in New York at the time — did much to bring the nascent scene back across the pond and into the British psyche. But as gangsta rap became the commercial face of hip-hop through the 90s, with NWA, Snoop, Tupac, and g-funk ruling the airwaves of LA, the hoodie took on new symbolism.

“Leisure and sportswear adopted for everyday wear suggests a distance from the world of office [suit] or school [uniform],” Angela McRobbie, professor of communications at Goldsmiths College, told The Guardian. “Rap culture celebrates defiance, as it narrates the experience of social exclusion.” Gangster rap took an overblown poetic vision of the realities of inner city life; but in the febrile, hot-headed world of tabloid media, gangster rap quickly became associated with crime and violence, and by extension, so did the hoodie.

In the UK, Tony Blair’s “tough love” approach to working class communities saw the garment vilified; hooded characters scurried through the pages of the mainstream media. As a result, inner city youth were stigmatized and the hoodie relegated, forbidden from schools, shopping centers, and nightclubs on both sides of the pond. In an article on the significance of the hoodie during the 2011 UK riots, Guardian journalist Kevin Braddock writes: “for the kids who live in the suburbs and inner-city estates where threat and violence are everyday realities, the hoodie is, above all, a tool for blending in, rather than standing out.”

Braddock continues: “For sure, a hoodie is a useful tool to avoid identification for a range of gang-related rituals. Yet for teenagers under intense peer pressure to conform to a collective identity, acceptance means adopting an prescribed outfit. For some, there may be no choice but to wear one and shoulder its associations.”

When grime arrived in the early 2000s — when MCs, DJs, and producers darted between bedroom studios, pirate radio stations, and vinyl cutters, often at a moment’s notice — its players confronted stereotypes with labels like No Hats No Hoods. Artists such as Dizzee Rascal and Wiley succeeded in bringing their soundtrack to mass audiences, becoming hoodie-clad heroes of a generation. Designers such as Nasir Mazhar took cues by intertwining the scene with their labels, bringing grime via tailored logo-covered tracksuits to the Men’s shows in London. Mazhar associates the hoodie with “life” and shares his thoughts with us on its influence in fashion: “The hoodie has become prevalent on the runway because it’s losing its former negative connotations and is starting to be seen in a new light.” When asked if he thought the hoodie is still synonymous with urban culture or whether it has been appropriated by fashion, he simply said, “Fashion is urban culture.”

This recent hoodie renaissance, however, should not be confused with high fashion becoming more “accessible” and “democratic.” It owes as much to cultural appropriation as it does increased social mobility. Fashion’s whimsically detached mantra of “elitism for all” fills much of the journalism surrounding these particular collections. But it’s hard to see how paying almost $500 for a hoodie can tap into the original iconoclastic and aggressive spirit of the garment.

Credits

Text Nazanin Shahnavaz