I cannot recall how or why I began watching The Summer I Turned Pretty in 2022. No one my age understood what I was talking about when I brought up that a girl named Isabel could (incredulously) be nicknamed “Belly.” For those that knew my penchant for modernist texts and classic Hollywood films, the question was always, “Why are you watching that?” as though it was out of character or beneath my interests. It seemed simple: I had been more than disappointed with the last decade of romantic comedies, and was grasping for anything that could elicit warm feelings, if any feeling at all. Depicting romance onscreen is not only measured successfully by the hope it inspires, but how it argues that any hurt incurred could very well be worthwhile.

The feeling that struck me first with The Summer I Turned Pretty was regret. I had the same sensation watching the previous Jenny Han adaptation, 2018’s To All the Boys I Loved Before. In both instances, it felt like living through a regular teenage life—something that I had skipped past too eagerly. I had spent my underaged years in Toronto being snuck into clubs and kissing boys with a questionable age gap between us. Watching the show made me understand the lesson adults tried to peddle of “not growing up too fast.” Things could have been so innocent and sweet! In another life, I could have stayed put in the lush, heady mess of being a teenager. Why would anyone want to grow up when the problems at hand were crushes in a Nancy Meyers-esque beach house, and an entire world coloured with Farrow and Ball paint swatches? Each week, I found it intoxicatingly quaint to be invited into the fantasy of The Summer I Turned Pretty.

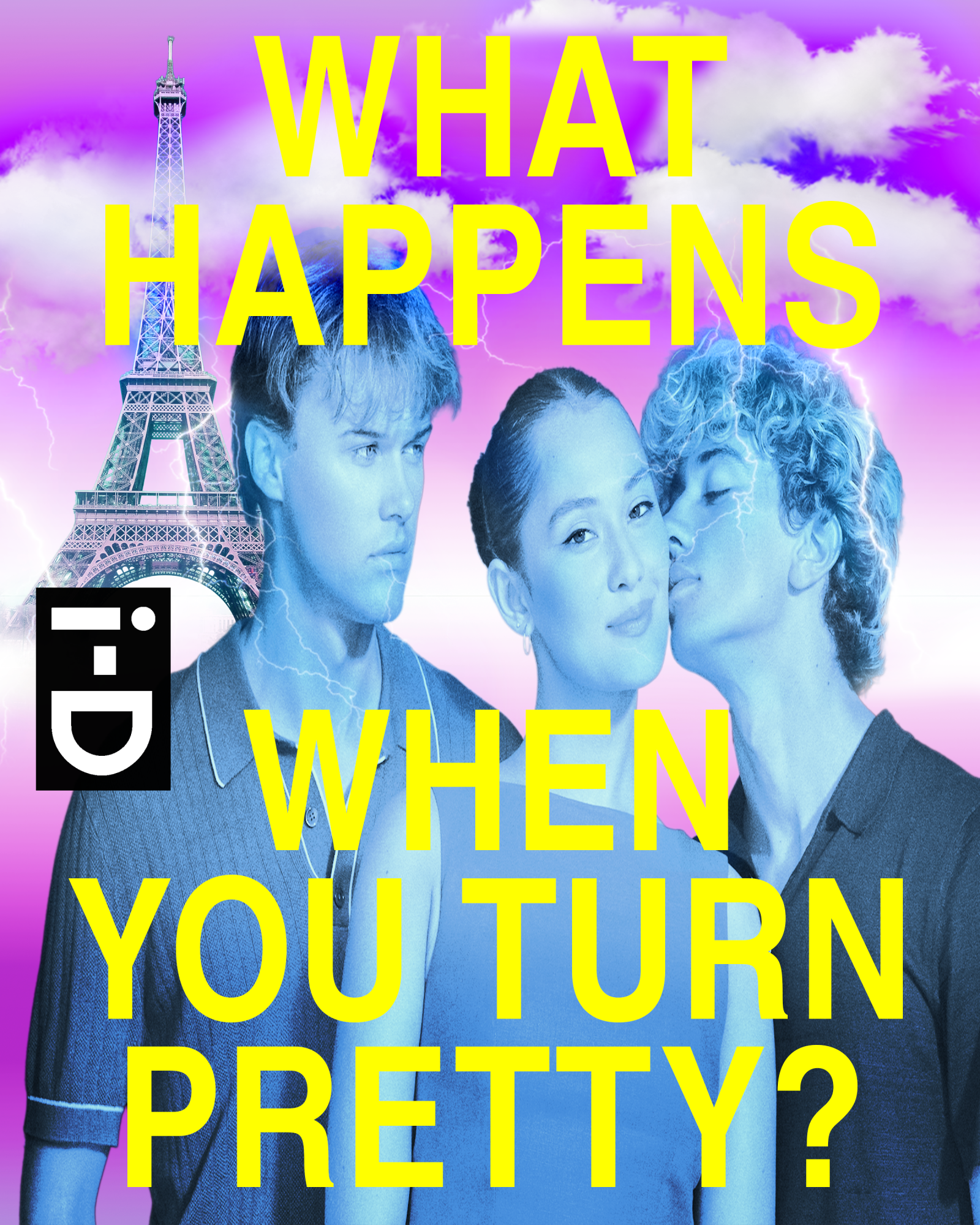

For a narrative to begin right when the duckling has found herself a swan is an unconventional start. Our heroine, Belly, spends three seasons not only grappling with the competing desires of two brothers, but finding herself thrust into young womanhood as someone who is suddenly found beautiful. The actors are all perfectly youthful, elastic, and have the kind of beauty you’d find walking between classes.

“They try to catch her before she realizes her beauty surpasses the borders of Cousins and a dating pool made of two brothers.”

Marlowe Granados

A love triangle has success as a story because it activates the audience and separates us into who we’d root for. As the dueling pair for Belly’s heart, the brothers Conrad and Jeremiah, symbolize two distinct paths for Belly (and us as their audience) to go down. Younger brother Jeremiah moves under the shadow of Conrad with the impish charm of a lion not yet old enough to break out on his own. By the third season, the brooding Conrad has the slumped posture of someone who knows they’re butting in. Who we choose to root for clearly defines our priorities and where we draw the line, and it speaks to how we moralize and what we value. The irresistible chemistry within this particular love triangle is enough to make you sigh and wish, “If only this happened to me.” It’s more believable and has more heat than most current films and tv shows for adults.

With films like The Materialists, the leading narrative we are being fed is how modernity complicates connection. Our romantic lives are calcified by separating us through several channels of communication, class, technology. Most of these stories are distracted with trying to be “signs of the times,” and forget that people fall in love with or without a thesis. The Summer I Turned Pretty cuts all that out by using the house in Cousins as its anchor, containing them for the most part, under one roof. As Greta Rainbow writes for The Atlantic, “The show offers a fantasy of a culture not so plagued by toxicity, allowing the creators to exchange the politics of the day for the nuances of growing up.” We can pare back and stay close to the feelings of our characters because there’s no other competing noise. The best part about being a teenager is that the stakes are so low, but the feelings are too large.

The series borrows heavily from Sabrina (1954) starring Audrey Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart, a progenitor of the brothers in love with the same girl genre. Like Hepburn’s Sabrina, Belly arrives in Paris to escape from heartbreak. Set against this new backdrop, Belly is cloyingly, painfully provincial. As I watch what I feel are my children growing up, it has become clear that the conflict has never been the choice between one brother or another. What takes us through has been Belly discovering the power of her beauty. The choice between the brothers, while yes, makes us swoon and wish we were the object of such unrequited and impassioned feelings, but we are no longer in Cousins.This final season has been a race against time for the brothers. The rush engagement to Jeremiah and its downfall, tied with Conrad making a break for Paris to confess his undying love no longer feels romantic. It is their last-ditch effort to keep Belly for themselves. For the first two seasons, Belly’s newfound beauty existed only for the brothers as her audience. Paris opens a third path, that these boys can no longer compete with. They try to catch her before she realizes her beauty surpasses the borders of Cousins and a dating pool made of two brothers. It is no longer the question of Conrad or Jeremiah, but how big or small does she see her life? If, as creator Jenny Han alluded to, there’s more beyond this last season I’d advise Belly exactly what Bogart tells Hepburn after she adjusts his hat: “Never resist an impulse, especially if it’s terrible.”