This article was originally published by i-D UK.

Set in 2001, to the backdrop of Israeli/Palestinian political tension and violence, Queerhana was a way to party the protest — and a way to politicize the party — at a time when the rave scene was apolitical. Co-founder and resident DJ Bosque Utopiko started the spontaneous free party movement to combat the otherwise dogmatic and uninspiring political activist scene. Now, the collective has released a retrospective book and documentary film, Queerhana: Utopia Now!, that documents this important chapter in the history of queer subculture in the Middle East.

Initial inspiration for the party came from the emergence of Black Laundry, an LGBTQ protest group who connected sexual oppression, social justice, and solidarity with other minority groups (especially Palestinians) and first appeared as a fresh political activist voice during Tel Aviv’s Pride Parade in 2001. Queerhana took that message one step further, deciding to organize events outside of state approved zones (like the Pride Parade), emerging as self-organized, non-commercial events that materialized outdoors, in squats and public places where every and anyone was welcome to join the party.

“There was a backdrop of violence that you’d see all around you and in the media that created a lot of tension,” Utopiko explains. “There was very strong oppression of the Palestinian population by the Israeli government. It was a kind of a point of depression because in the 90s there was hope for peace and for change. It was the time of the Second Intifada [the second Palestinian uprising against Israel] so we had buses exploding in our neighborhoods, next to cafes we used to sit in, it was not something you watched on TV, people you know might be there. We had this insane violence in our neighborhoods and we felt the political situation was getting crazy.”

Incorporating the philosopher Hakim Bey’s notion of Temporary Autonomous Zones, with a nod to the Reclaim the Streets movement and the 90s New York club kid scene and their flashmob parties in locales like McDonald’s, Queerhana began to create improvised islands of anarchy in public spaces. Empty fountains in parks became dancefloors, underpasses morphed into rave tunnels, closed highways with their roadwork decor, and giant sandbags became post-apocalyptic free party zones.

“Back then, in the center of Tel Aviv, you had a bunch underpasses, people used them as toilets mostly. We’d come and wash them and have parties there or we’d make parties on the highway and when the law came and kicked us out we’d go underground,” Utopiko remembers. “People would help us carry the sound system and it was like everyone was taking part and nobody stole anything even though it was expensive equipment.”

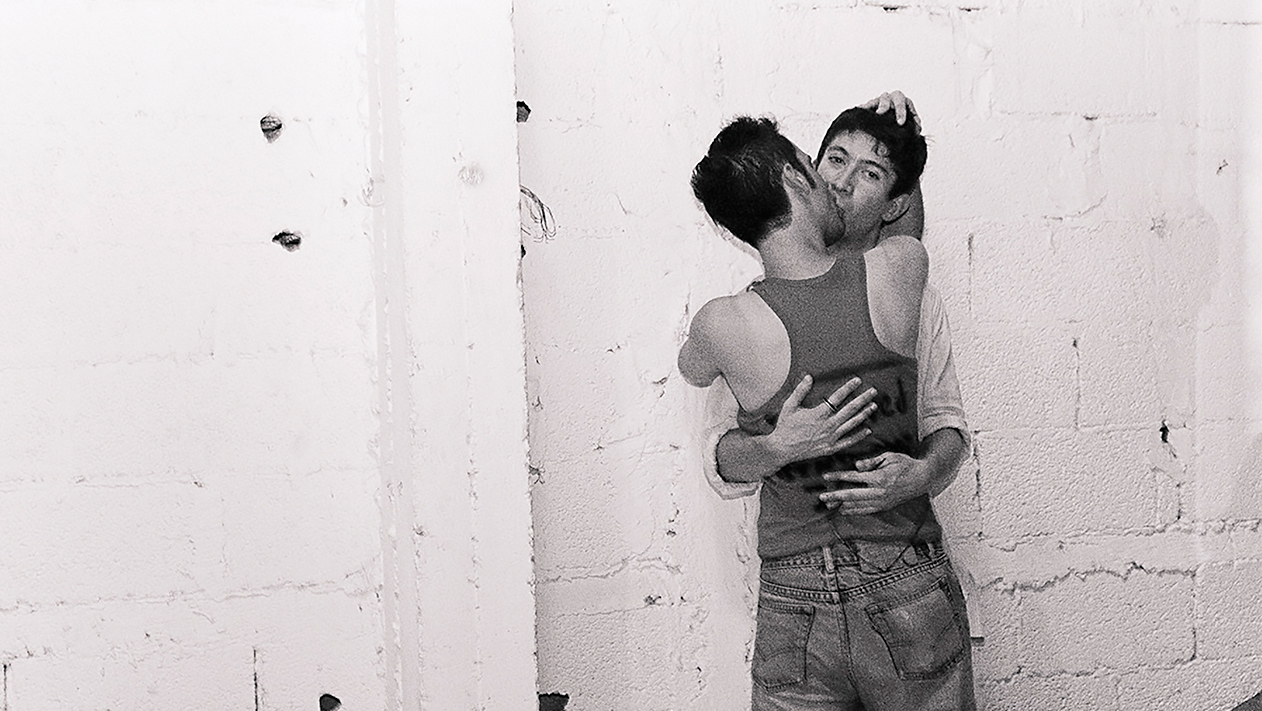

The result was an unlikely mix of what Utopiko describes as “queers, punks, activists, and homeless people” coming together to party purposefully. “Once there is no security and no hierarchy in a space, people act differently,” Utopiko muses, “they feel differently and they take more responsibility, it promotes community, when you open up a party in the street anything can happen.”

Utopiko describes his defining memory of Queerhana as a moment during the second Lebanon War in 2006, when the atmosphere in Israel was polarized. “It felt very us and them, Jews against Arabs,” he says. At the height of Queerhana’s popularity, in front of a huge crowd, a group of Palestinian drag queens did a performance that expressed their feelings of loss, personal and national mourning from their own Palestinian perspective.

“Many people that were there were not necessarily very political and suddenly all these people, during war time, were exposed to this voice with no filter. I remember standing there with shivers and I really felt that we were doing something special and making a change. There was only one narrative and one energy in the city at that time, hatred, revenge and I felt we made a connection in that moment between two so-called enemies. Some people in the crowd were like, ‘Hey what the fuck!?’, they couldn’t believe this performance that was in Arabic, but many people made a connection. It really touched me and empowered me as a spectator and a contributor to the event. It felt spiritual.”

Although there were fines, noise complaints, and a few notable clashes with police during Queerhana’s life span — along with the odd passerby calling them “communists” — for the most part the parties seemed to truly transcend their illegal occupation of spaces, temporarily existing in lawless alternate rave realities.

“It was like an explosion that affected people really strongly. I saw the after-effects of that when I edited the book. I didn’t know if people would want to contribute and then when I started asking people I received all these essays about how it affected their lives and their art and identity. To say Queerhana succeeded doesn’t mean Queerhana saved Israel at all. This was not our goal, we were humble, we didn’t think we were going to save the Middle East. A lot of people ask why it ended, but I think it had a natural cycle. If it had continued it would have lost its spark.”

The Queerhana: Utopia Now! book and exhibition were produced as part of a project with the nGBk gallery in Berlin. The book can be ordered at Verlag.

Credits

Text Russell Dean Stone