Museum of Transology, the largest ever UK exhibition of trans artifacts and portraiture, opens to the public today at the Fashion Space Gallery — a small but impressively programmed exhibition space housed at London College of Fashion in Central London.

The Museum presents film profiles and portraiture alongside over 120 artifacts donated by members of the trans community, objects that chart the modern social, cultural, medical history, and diversity of trans lives. The exhibition brings together a moving collection of first lipsticks, bras, prosthetics, packs of hormone pills, trans pride souvenirs, and even post-operation body parts.

Curator E-J Scott is a dress historian, queer history researcher, and archivist who previously worked on the Biba & Beyond: Barbara Hulanicki exhibition at Brighton Museum and is currently a researcher and archivist for Duckie — the legendary Vauxhall club that gave London its new Night Czar, Amy Lamé.

As the Museum of Transology opens to the public, i-D caught up with E-J to find out more about this groundbreaking exhibition.

How did the idea for the Museum of Transology first come about?

The show grew out of my own collection of artifacts, saved after a surgical procedure that was part of my transition. I kept everything from the towel to my hospital gown, the medical cups I was administered medicine in, my morphine syringe — the lot. The surgeon even pickled my body parts in formaldehyde. I realized, having worked in the heritage sector, that there is a complete dearth of trans narratives, and that even this collection could not find a suitable home. So I started proactively collecting objects and stories that have built what I now call the Museum of Transology. It will be a gift to any heritage institution who wishes to address trans invisibility and the erasure of trancestory in the museum.

What was your brief to the people who donated artifacts?

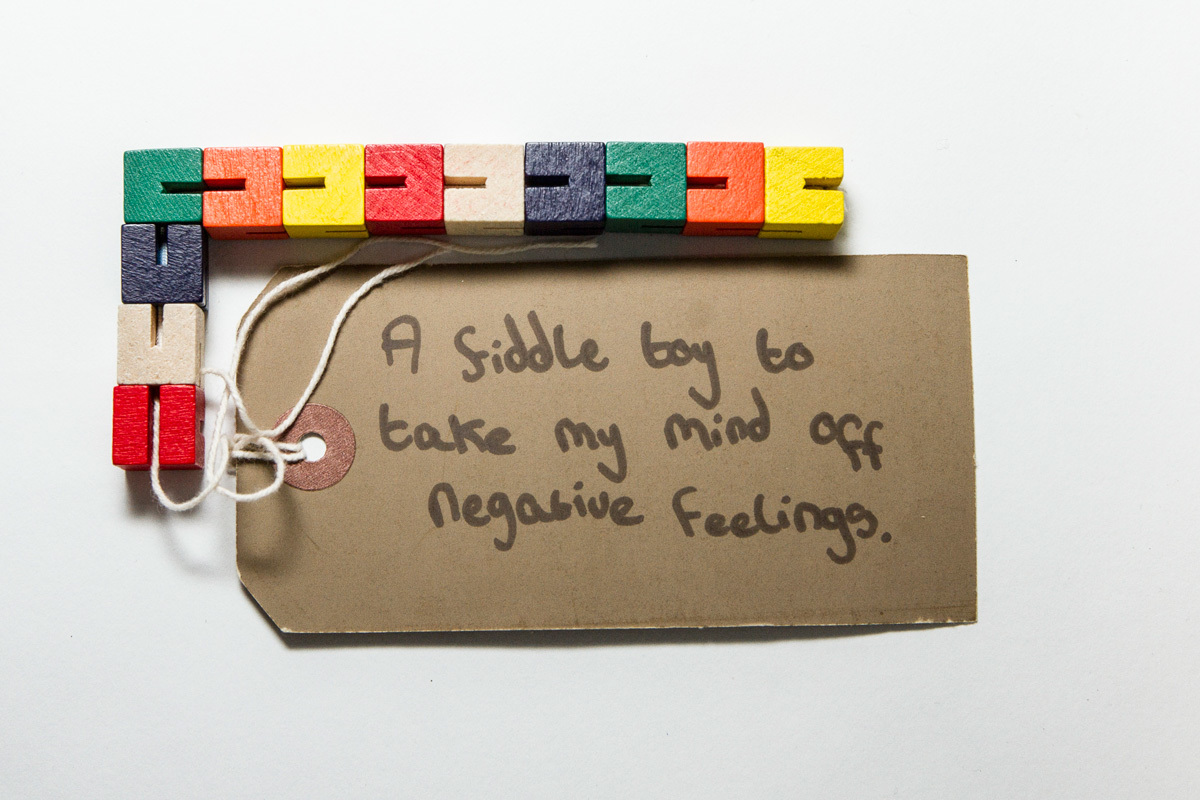

I was clear that people could choose an object personal to them — there was no stipulation as to what that object might be. Donors were also asked to fill out a travel tag in their own handwriting, explaining the significance of the artifact. This protects the object’s story; these are everyday pieces that have genuine, authentic voices attached to them. They cannot be separated, so they cannot be overwritten by a cisgendered curator, should they find a home in a museum. The objects are made extraordinary because of their intimate nature — from ‘first bras’, to a collection of hormone packets, to a pair of ballet shoes, and a My Little Pony. They share themes of hope, despair, ambition, desire and reflect the increasing confidence of the UK’s trans communities and a growing willingness to tell our stories.

What is the importance of collecting and showing these artifacts?

Because trans people rarely work in the museum sector (if you aren’t visible in the museum, why would you want to work there or think that you are welcome to?), nuanced and hidden trans stories have rarely been identified. This means that trancestory has been erased from history — lost, overlooked, frequently neglected. In order to preserve this historically important moment of trans history and the history of a broader social shift in the UK’s understanding of gender being on a spectrum and not biologically determined, it is essential that trans people’s stuff and stories are collected and preserved now, before it is erased again.

It is also essential that these are real stories told by real people, not a hyper-spectacular narration of trans lives by the popular media that generally focuses on ‘Peeping Tom’ exposés or before and after surgical ‘success’ stories. The exhibition is a collection of over 120 everyday objects and stories that are as diverse as the gender journeys they represent.

One criticism of the way trans identities are discussed in mainstream culture is the obsessive focus on body parts. Why did you think it was necessary to include these post-surgery artifacts?

These artifacts do not spectacularize the idea of the trans body trying to achieve some kind of cisgendered sewn-together mannequin type of copy ‘success.’ They are a real person’s body, and they are accompanied by a real story: my story. They started this collection and mark a shift in my own journey. The destructive and clichéd idea of ‘passing’ denotes that others ‘fail’. That’s why the body parts are accompanied by an image by fashion photographer Barat Sikka that exposes the results with scars, and promotes the idea of engaging with trans embodiment — proudly asserting that we have wondrous trans bodies that are unique, our own, and not to be ashamed of, or disappointed in. This is a story of empowerment, not embarrassment, a display of trans entitlement, not cisgendered titillation.

In what ways have trans histories been excluded from museum collections?

Trans voices and lives and identities have historically been read as expressions of alternative sexualities rather than expressions of non-binary or alternative gender, or have been considered to have been employed as a career strategy designed to overcome workplace gender restrictions (i.e. dressing as a man to appear to be a man in order to enter a male dominated field). These singular narratives exclude trans lives. Trans lives themselves historically have been hidden as a matter of survival. In combination, there has been an erasure of trancestory.

And what steps can be taken to make collections more inclusive?

This collection needs to be accessioned by a UK museum with a social history remit, and is a gift to any institution wishing to address the invisibility of trans narratives. It must be protected and preserved and allowed to grow in order to trace this extraordinary ‘theirstory’ that is in the making. Trans lives have a far broader social impact than solely on trans people themselves — they are direct challenge to the idea that gender is fixed and biologically determined, an extension of feminist theory. Trans lives reflect the continued struggle for equality for all, regardless of gender, and as such, are an important contribution to the social history of the UK.

Tell us about an artifact that moved you?

This is a brave and ambitious collection, full of honest and intimate stories. One of my favorites is of a ‘fiddle toy’ that the young person uses to help distract them from negative feelings. Another is a pair of tiny ballet shoes that were the first belonging to a young trans man who still performs pointe and has overcome his fear of gender stereotypes that he initially thought may stop him from being able to dance whilst expressing his masculine identity. He has had a complex and thoughtful gender journey and arrived in a confident and creative space.

What do you hope visitors will take from the exhibition?

My wish would be that this exhibition despectacularizes what it means to be trans, and helps show the world how confident and ambitious the UK’s trans communities are becoming. I hope that it raises awareness surrounding the increasing violence against trans people in the UK, and communicates the importance of understanding trans lives as being part of a fight for gender equality for all. I hope it makes every visitor think about what their own gender really means to them, and helps free us all from any constraints that limit who we are, who we can be, and what we can achieve.

Museum of Transology is open to the public through April 22, 2017 at the Fashion Space Gallery, housed at London College of Fashion.

Credits

Text Charlotte Gush

Photography courtesy Fashion Space Gallery