The Broderip Ward began welcoming patients in January 1987. Housed in Middlesex Hospital, an official opening followed in April, marked by a visit from Princess Diana. As the UK’s first specialist unit caring solely for people affected by HIV/AIDS, the event was highly publicised, and remains widely celebrated. For those in the ward’s care — predominantly young gay men, some of whom weren’t yet out to their families — the fanfare was keenly felt, and many patients chose to move wards for the event. Only one person agreed to be pictured with the royal, photographed from behind to avoid being identified. By the time Gideon Mendel arrived at Broderip in 1993, the plaque commemorating the occasion was covered over.

“I never learned if it was true, but people believed there were photographers from The Sun in the surrounding buildings, attempting to photograph and out people,” the South African photographer tells me. “There was a huge fear of the camera, it felt like the camera was the enemy.” The stigma assigned to HIV/AIDS at the time was immense, routinely upheld by the media and effectively backed by Section 28, the wildly homophobic legislation implemented under Thatcher five years earlier. Writing in 2018, Stephen Mayes, managing editor of Network Photographers between 1989 and 1994 — Gideon’s then-agency — referred to the unfolding crisis as “a medical condition that became a social condition,” describing the narrative in the early 90s as “drowned compassion in a sea of populist cant.”

Under his direction, in 1991 the agency collaborated with the Terrence Higgins Trust to establish Positive Lives, a photographic project documenting social responses to the developing epidemic. Honouring the charity’s tenth anniversary, the work was exhibited in a group show at The Photographers’ Gallery in 1993; one of Gideon’s Broderip images fronted the accompanying book. 25 years later the photographer returned to the series, publishing The Ward with Trolley Books in 2017. Recently reissued, a corresponding exhibition, The Ward Revisited, opened earlier this year at Fitzrovia Chapel (through 5th February). The only building from Middlesex Hospital that still remains, the new installation places Gideon’s images close to the locale they were made.

“It’s minor today, but I went through the hectic experience of having an HIV test in the early 1990s, which involved an hour of counselling before and a three-day wait for the results,” he continues, explaining how he came to be on site and relaying the genesis of his early intrigue. Gideon had just returned from a stint in Somalia, and was ill with hard-to-diagnose symptoms. He spent ten days on a ward for tropical diseases at Middlesex, learning about Broderip and its sister ward, Charles Bell, via one of the doctors. He would go on to spend 15 days over a six-week period on the ward for Positive Lives.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

“It was a delicate situation to negotiate, the staff were very protective of the patients and I was very much on the periphery,” he says. “Patients were curious about me, I spent a lot of time just talking to them. For various personal reasons many couldn’t be photographed, but there were a few who liked the idea of being witnessed.” Four men, John, Ian, Stephen and Andre — as well as their respective families, including John’s mum Patsy and Stephen’s sister-in-law Sarah — agreed to be photographed. “People often don’t recognise what an incredibly brave thing it was for them to do,” Gideon says, alluding to the hostility they faced. “Things have changed so much since then.” As Stephen Mayes recalls in the book, when the images were first published — not long after John had died — Patsy received a brick through the window.

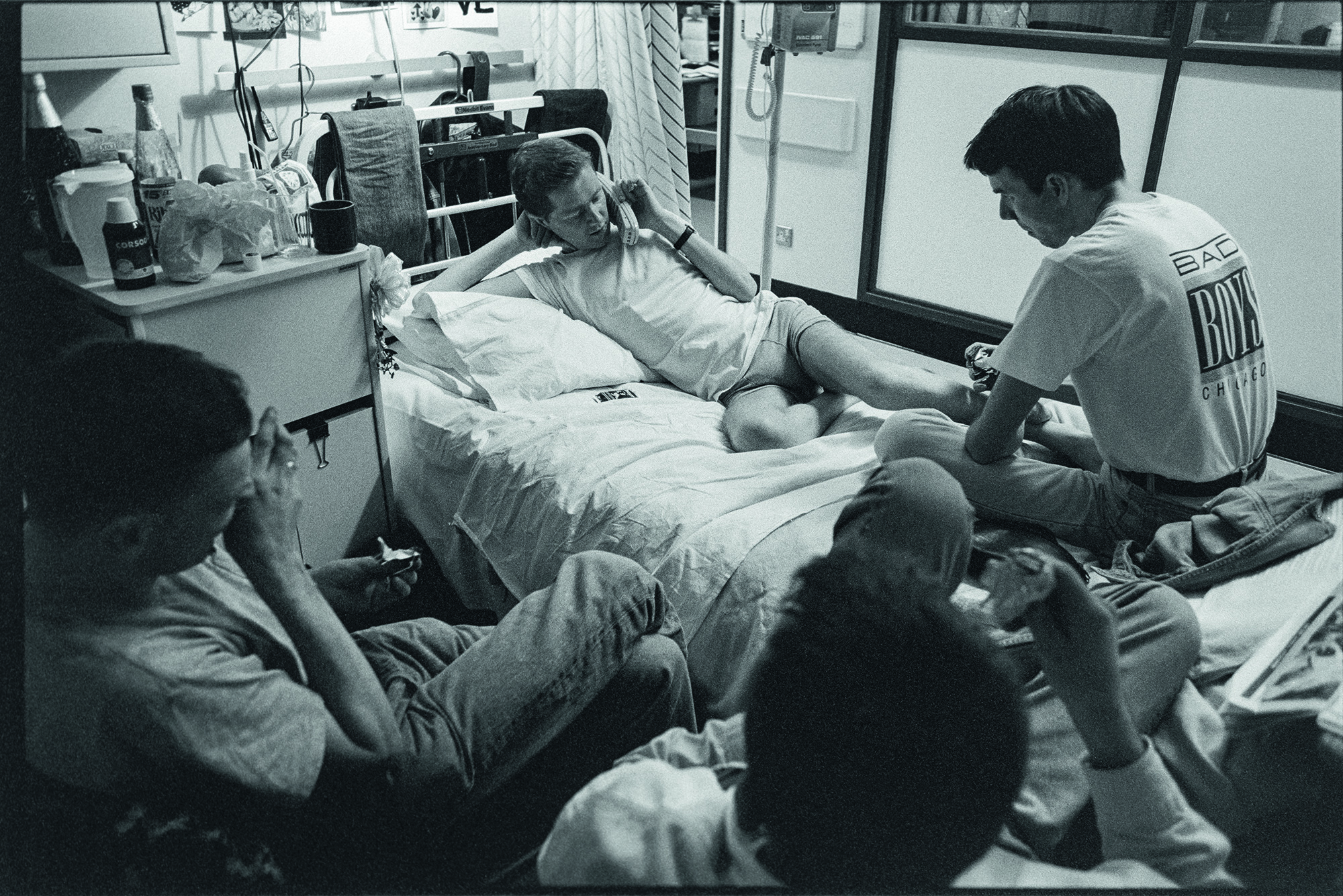

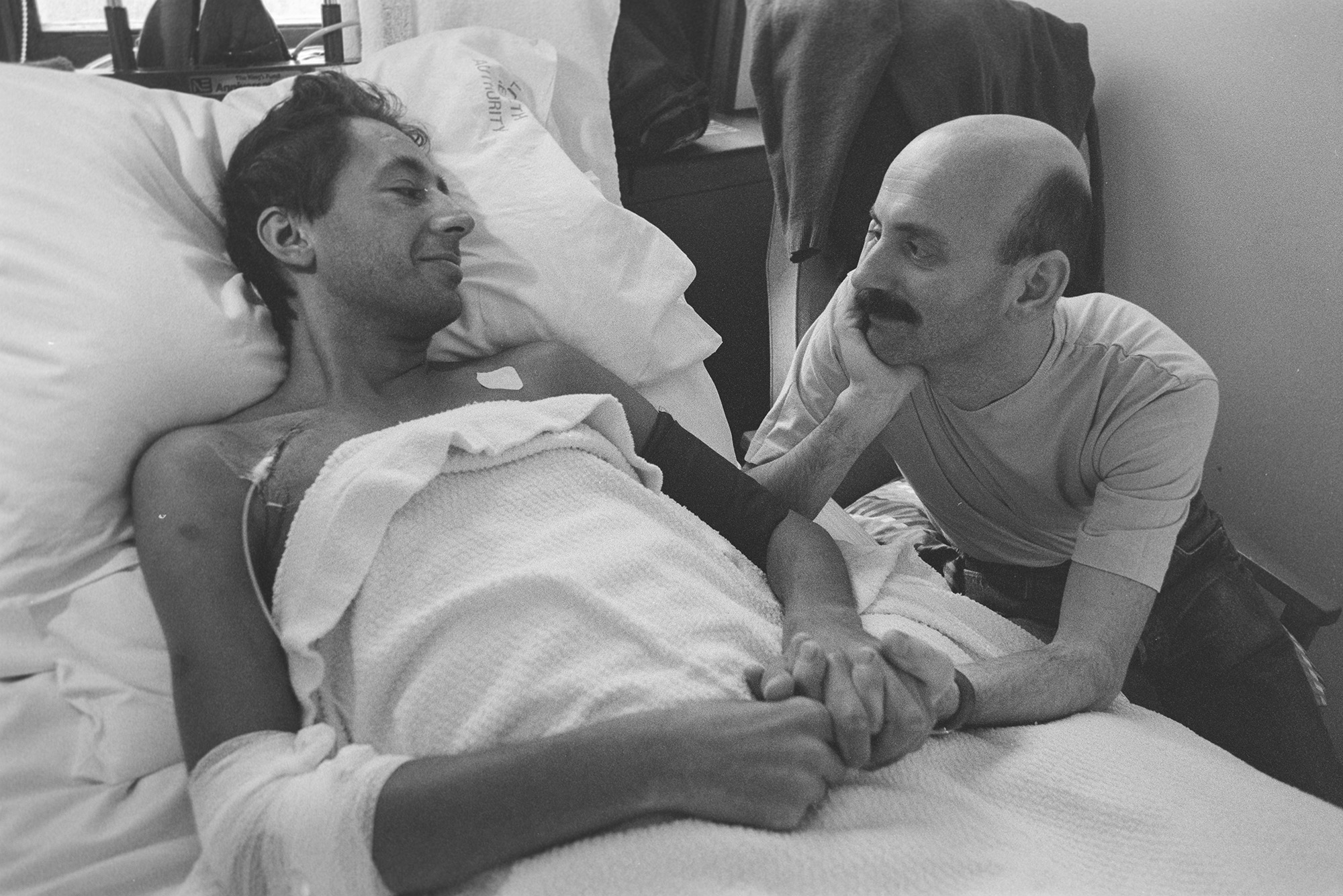

The ward itself, however, went beyond even acceptance in its consideration of care and affection, operating with a unique sensibility that focused on humanity, countering the typically sober surroundings. “There was something special going on, particularly in the kind of physicality,” Gideon says. “I think to almost counter the stigma, they’d decided to make the ward a very warm place; staff were encouraged to touch patients, which was against so many of the principles of nursing. They worked hard, creating a light, happy atmosphere, and you could sense the patients really felt seen and well cared for.”

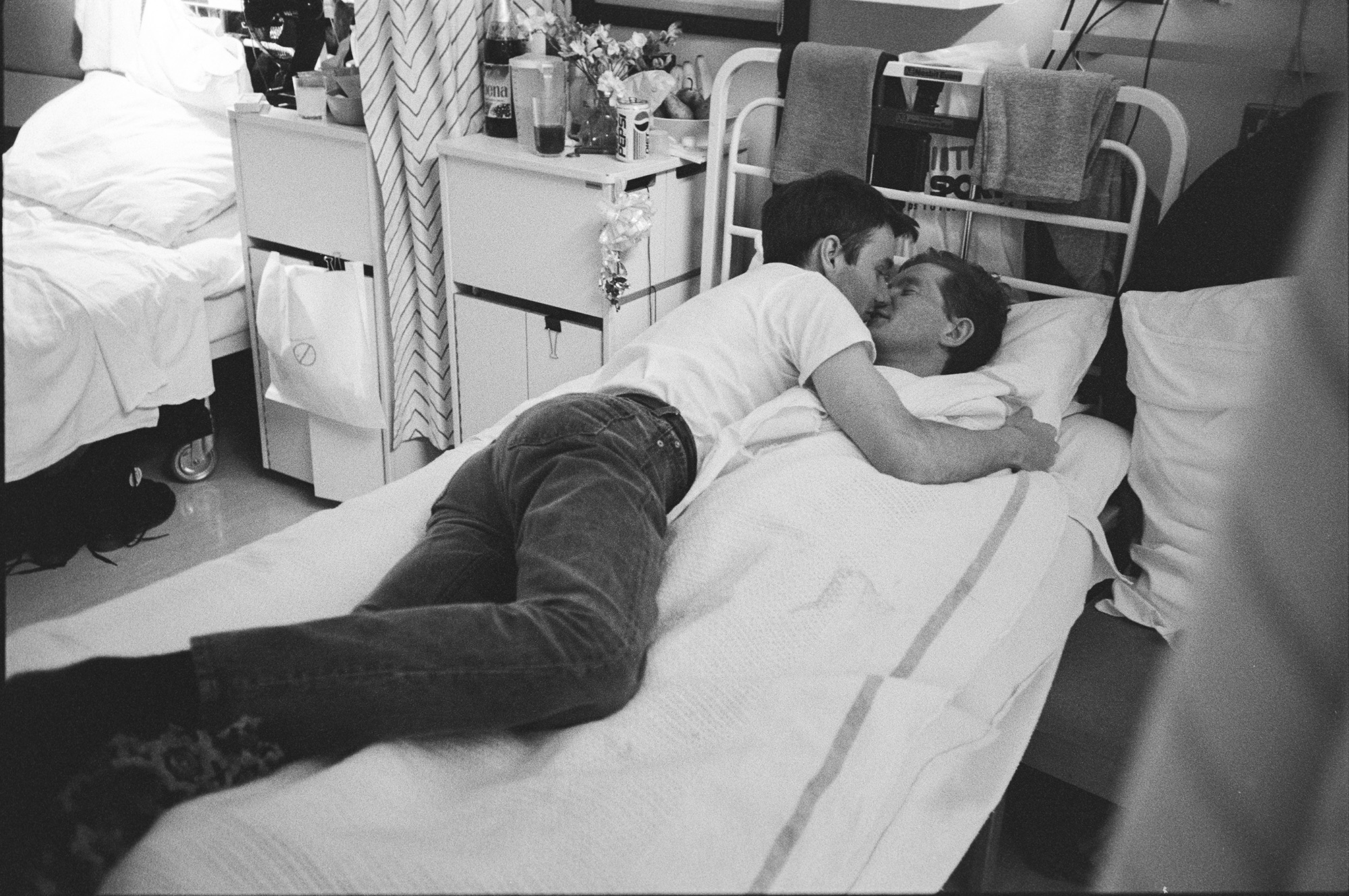

In his images, stolen moments are centred: patients sharing an embrace with a partner, receiving a kiss on the cheek, or simply smiling with their parents. “There is a background of death to the whole thing,” Gideon acknowledges, “but patients had lots of friends coming to see them, creating an amazing atmosphere.” There were parties with drag queens, beds left empty as patients went clubbing, and personal notes like cards, flowers and even fish tanks decorating rooms. “There was a sense of it being a terrifying, monstrous thing [AIDS] and people with the disease being these emaciated monsters. I just wanted to show these four young men in a very normal way, surrounded by a lot of love.”

The ward had a profound effect on the photographer, whose practice has continued to engage with HIV/AIDS, most notably with Through Positive Eyes, a project that gives the camera to those directly affected. Now, more than 30 years after The Ward came into being, there is a strong sense of responsibility. “I feel a stewardship. These photographs are quite emotional, and it’s a complex responsibility to honour the memory of these four men,” he says. “What has surprised me is the way interest in these photographs seems to be growing with time. [Previously] I couldn’t imagine a book like that selling well because my perception, having done a lot of work on the issue, was that people didn’t want to know about HIV and AIDS, but it completely took off.”

The gay community especially has widely embraced the series, and an image of John and his partner, sharing a kiss on a cold hospital bed, has become symbolic within the canon of queer visual storytelling. “David Gere, one of the co-directors of Through Positive Eyes and I had this conversation recently,” Gideon adds. “He’s gay, I’m a relatively conventional, straight heterosexual person, and he said, ‘I don’t know how this has happened, but a boring heterosexual like you has created this iconic gay image’. It is an image of HIV but also, it’s become a very iconic image of gay love. Maybe it was easier because I was an outsider? Certainly it’s had a long life and impact, and I’m really proud of that.”

Gideon’s exhibition ‘The Ward Revisited’ will be showing at Fitzrovia Chapel in London until 5 February 2023. Entry to the exhibition is free. You can also buy a new updated edition of “The Ward” from Trolley Books.

Credits

Photography Gideon Mendel