Wes Anderson, the man whose stacked casts and uniform, candied aesthetics are so consistent that his name is now an adjective that has seeped into the real world, is seldom associated with newness. But in The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, his latest movie that just premiered at the Venice Film Festival, the director feels like he’s in experimental territory. He’s riding on a high: earlier this year, his latest feature Asteroid City premiered at this festival’s direct competitor, Cannes, to a sea of strong reviews.

In some ways, Asteroid City crystallised what Wes is so great at. It was a love story, but also a deep thinker’s reflection on grief and responsibility — mixed with a tale of alien-fuelled hysteria. It was a well decorated opera cake, each layer important. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, one part of a soon-to-be-unveiled anthology film made up of Roald Dahl’s short stories. Henry Sugar is the longest of the four; the others, Wes confirmed at a press conference, are The Swan, Ratcatcher and Poison.

We were promised something different a few months ago, when Wes told a journalist that Henry Sugar was “not a movie”. Technically, that’s incorrect, but spiritually, you can see where he’s coming from. Henry Sugar is a neat, zippy package: a film presented with the fluidity of theatre and the dexterity of Roald Dahl’s literary language.

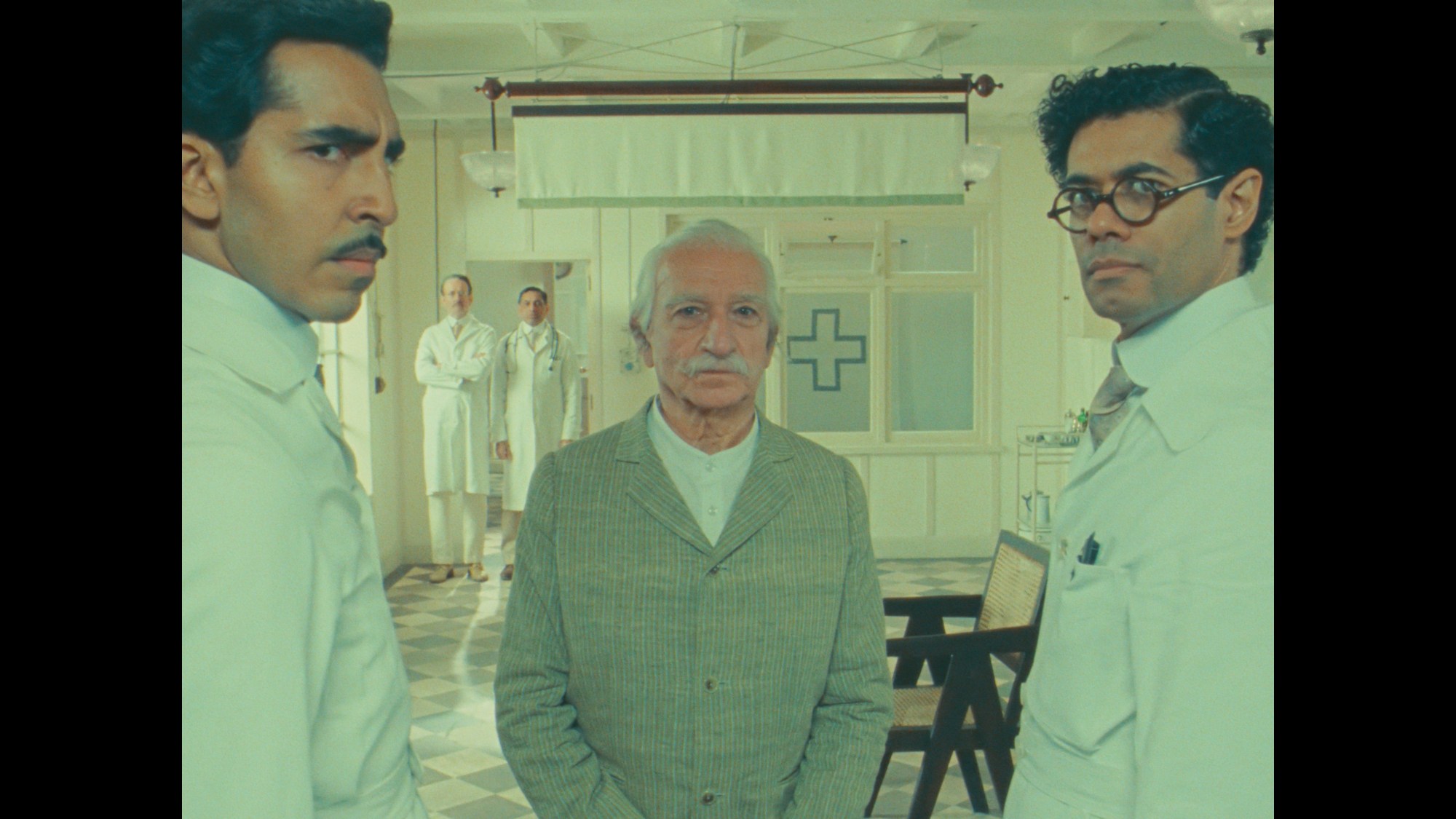

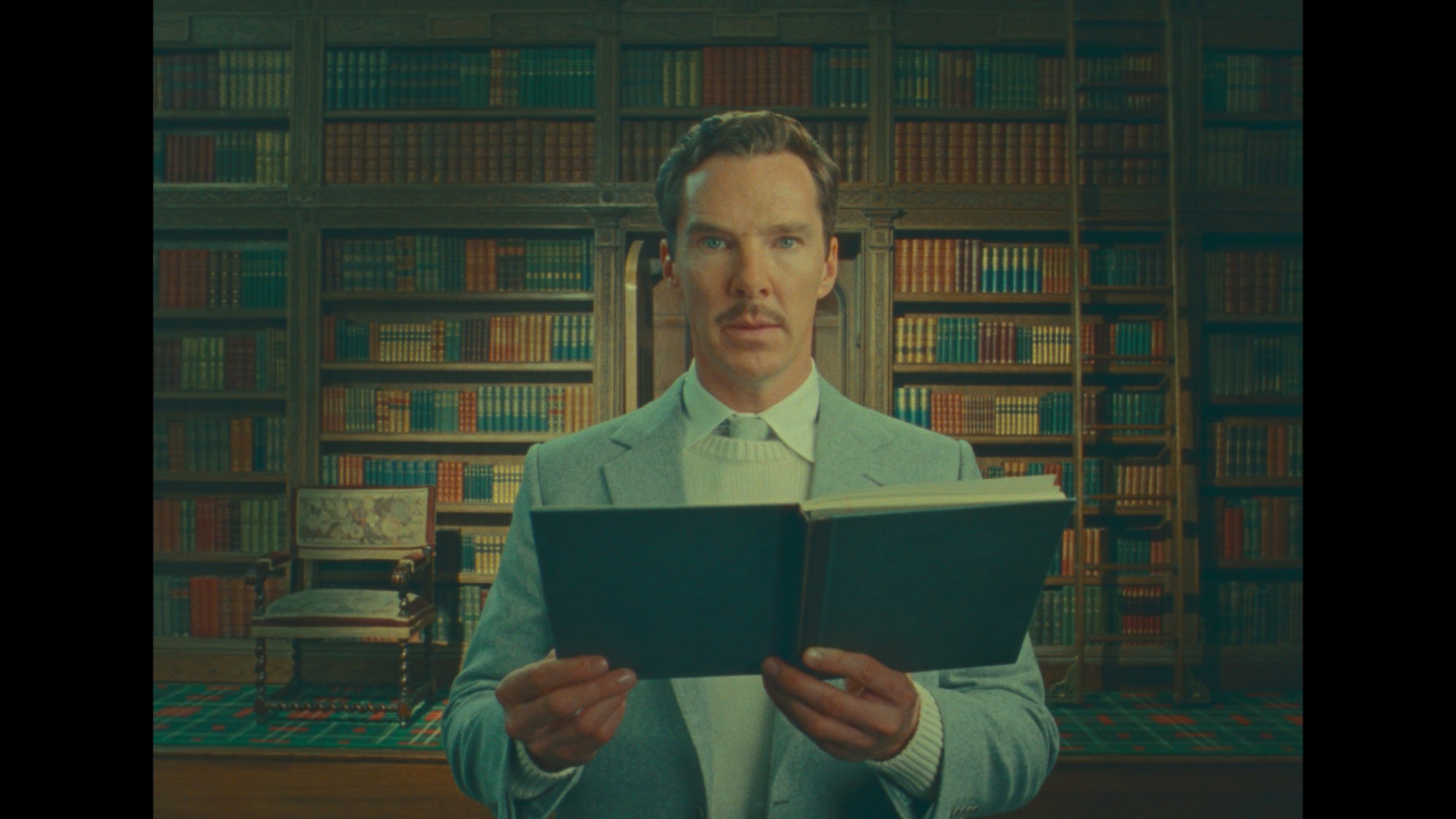

The film makes much use of both: Roald’s Henry Sugar story is a Russian doll tale, with characters almost living inside the voices of others. In the film, as in the book. the titular character (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) is a pompous Englishman who walks through life with the kind of languorous energy reserved for the rich. On a rainy day in a friend’s mansion — with all outdoor activities off limits — he stumbles across a book in the library written by a doctor, Dr Chatterjee (Dev Patel), recounting the story of Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley), a Yogi guru who miraculously claims to be able to see without the use of his eyes. Henry, a sleuth, sees potential in his practise as a moneymaking scheme.

Wes Anderson treats Roald Dahl’s words so sacredly that he is actually in the film: Ralph Fiennes plays the author in the film, sitting in the writing hut at Gipsy House, his home. He has his own dialogue, and he starts the tale’s narration before passing it on from one character to the next.

The film in parts sees its characters recite his writing verbatim, down to the “he said” and “I said”. It feels like a radio play performed on stage: screens fall in front of characters; stage lighting visibly switches from one angle to the next, as if we’re in the stalls watching it unfold in front of us. Special effects are non existent, instead there’s an obvious practical element to these moments. (When one character learns how to concentrate so well he can float above the ground, a box painted to resemble the also painted backdrop props him up.)

It’s a film full of texture and colour, so decadent and alive that you can get swept up in its visual beauty. But that Roald Dahl sense of strangeness, the sense of humour, is baked lovingly into its frames.

‘The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar’ will be released in cinemas on 20 September, before being released on Netflix on 27 September. This review is from the Venice International Film Festival.

Credits

Images courtesy of Netflix