“When I first went to university It really was a culture shock. I met some incredible people but I’d also never met so many people who were wealthy or attended private school,” says Seren Metcalfe, a Yorkshire-born artist currently in her final year at London’s Slade School of Fine Art. “At the beginning I didn’t think It affected me but looking back my first two years at university were spent adjusting,” she recalls. “I felt like I was the only one in my subject area with a Northern accent, or constantly worrying about money.”

Metcalfe’s experience of feeling outnumbered by the middle and upper classes is sadly not something she’s likely to leave behind after she graduates. Against a backdrop of austerity and a culture of classism and unpaid internships, it’s increasingly hard for anyone not from a wealthy background to break into the arts world. In 2018 in fact, it was reported that only 12.4% of those currently employed in the creative industries come from a low income background.

In order to help correct this, Seren has formed her own collective: the Working Class Creatives Database. Currently existing as a digital platform and Instagram page, the project’s aim is to highlight the talents of working class individuals across different artistic fields as well as create a network for curators, programmers and gallerists to refer to. With 51 creatives working across poetry, visual art, acting and publishing currently listed, it’s at the beginning of its journey to becoming a much-needed port of call for individuals looking to nudge the arts into a more diverse direction.

Seren hopes that one of the ways her database will disrupt the art world is in the industry’s insidious nepotism problem. “One thing I really learned from moving to London is that it really is about who you know,” she says. “Nepotism is an important part of the creative world, as shit as that is. It’s partially dominated by middle and upper class people because they’re all so well connected with one another and it’s all so centralised around the capital.”

It’s not just instances of nepotism and erasure that impact working class artists, though. A more blatant, unapologetic classism still exists as well. As Tommy Sissons, a London-based poet, political writer and playwright listed in the Working Class Creatives Database, explains, there can be pressure to obscure a working class background within certain professional contexts. “I am still in the conscious habit of putting on a ‘standard English’ telephone voice when I am talking to a high-end arts organisation, as I would do if I were going for a job interview in a hotel,” Tommy says. “This is purely because regional and working class dialects are still considered somewhat grotesque to those who benefit the most from the arts industry.”

Working class creatives also have to contend with fewer opportunities at an early age thanks to slashed budgets in an age of Conservative austerity. “The numerous cuts to arts grants and the closure of youth centres and libraries in recent years have greatly limited the access of working class youth to creative spaces in their local communities,” Tommy continues. “Similarly, the cuts made to subjects such as art, drama and music in British schools has taken the opportunity to engage in creative expression away from many working class children and further isolated them from the arts industry.”

For some individuals from low-income backgrounds that make it into a career within the arts, the focus can fall on beginning to shrug off middle and upper class hegemony in order to make room for other working class people and the class and regional aesthetics they might subscribe to. This is the case for Lolly Adams, another creative listed on the database, who works as an artist, a teacher and the curator for The Other MA project space in Southend-on-Sea. “To be honest I think the classism that I experience is probably happening without me even realising. Who knows how many opportunities I’ve missed out on because of my accent or etiquette, but I don’t care!” she says. “I’m up for being part of a different art world that’s void of those kinds of structures or judgements.”

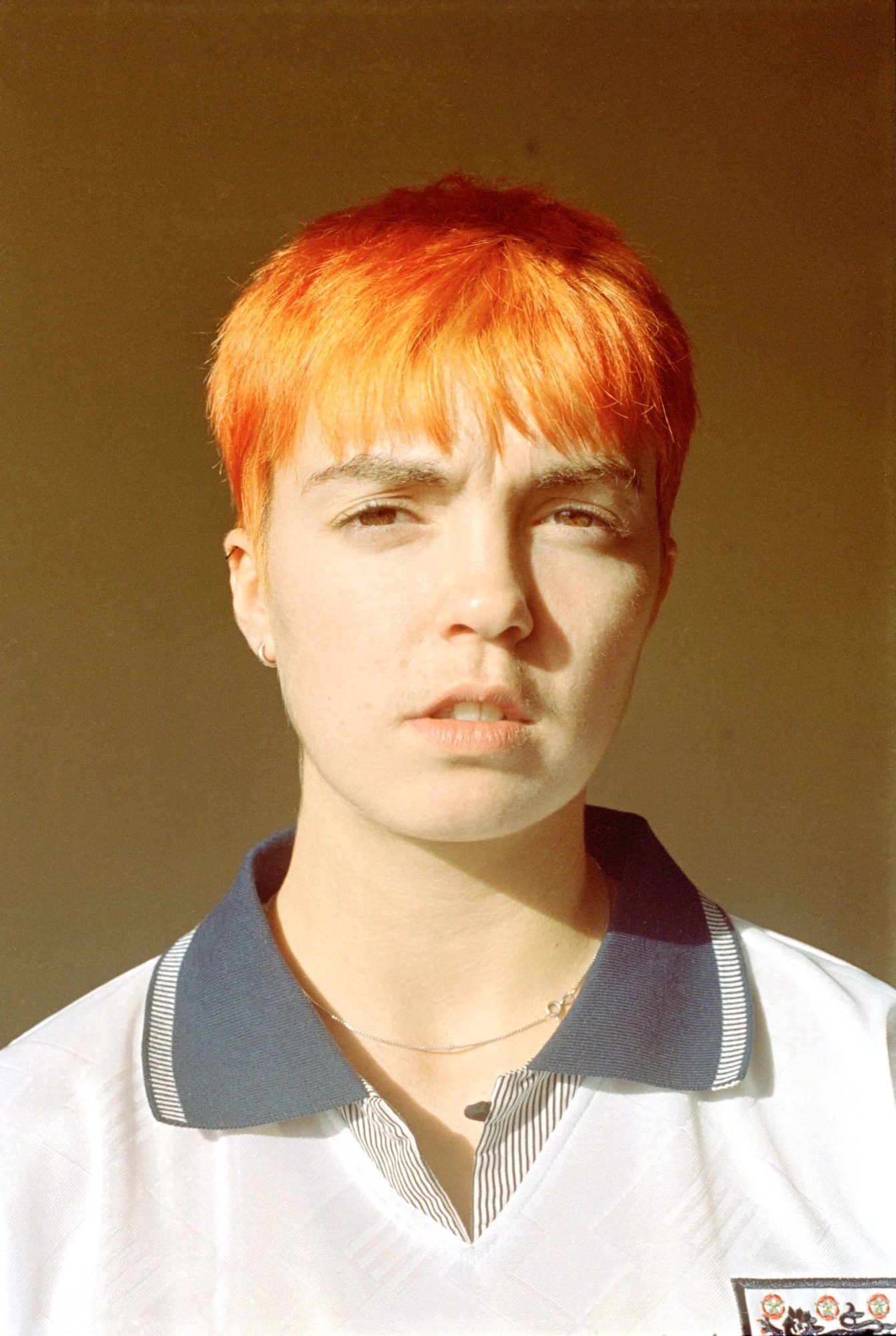

Similarly, photographer Heather Glazzard is another Working Class Creatives Database artist that wants to push back against bourgeois assimilation. “There’s definitely more of an appeal to try and make your work fit into a middle class world because of the attraction of money,” they explain. “But for me, personally, recently I’ve felt that I need to speak more openly about my class through my work.” Whilst platforming class issues can be a form of catharsis for working class artists like Glazzard, Adams explains that more well-off artists are also prone to appropriating and coopting these narratives. “I’ve been part of WANK, the Working Class Artists Network, which embodies the taste and demeanour which I feel more at home in,” she says. “But I’ve noticed that middle and upper class artists use this aesthetic too. Even a year into art school I realised that my working class cultural capital was something that [middle and upper class peers] wanted to assimilate but could never have.”

It’s still a work in progress but Seren’s database is doing important work by recognising the power of this kind of perspective and by helping working class artists organise to resist the reigning middle and upper class mediocrity. But beyond these solid foundations, what does the future hold for the project? Ultimately, Metcalfe hopes to find ways to expand the database into the IRL realm. “I see the database becoming much more than a list on the internet,” she says. “This is the beginning of something great but it still feels contained within a bubble; I’m looking for ways the database can reach communities that need it.”