There’s a cautiousness to Nadia Lee Cohen. The photographer-filmmaker is mindful of her words, her associations, her ‘brand’. And with ‘cancelation’ rife for successful creatives (and the executioner’s axe now as menial as a popular tweet), it’s only natural that hyper-consideration become par for the course. But there’s more to it with Cohen. It seems as though she doesn’t fear the fragility of her cultural clout, but that people might uncover she never had any to begin with.

Perhaps that’s the reason the LA-based-Brit sweats self-deprecation. Upon charting her career highlights — which, for the record, include a National Portrait Gallery prize, a high fashion campaign starring Sophia Loren and a music video named among Rolling Stone’s favorites — she responds by comparing herself to her contemporaries. When congratulated on her accomplishments (all by the age of 26, when most are only beginning to tackle credit card debt), Cohen counters, “Have I [done that much]?” While it may be in the Hollywood handbook that transplants exhibit imposter syndrome, Nadia Lee Cohen needn’t. Her work speaks for itself.

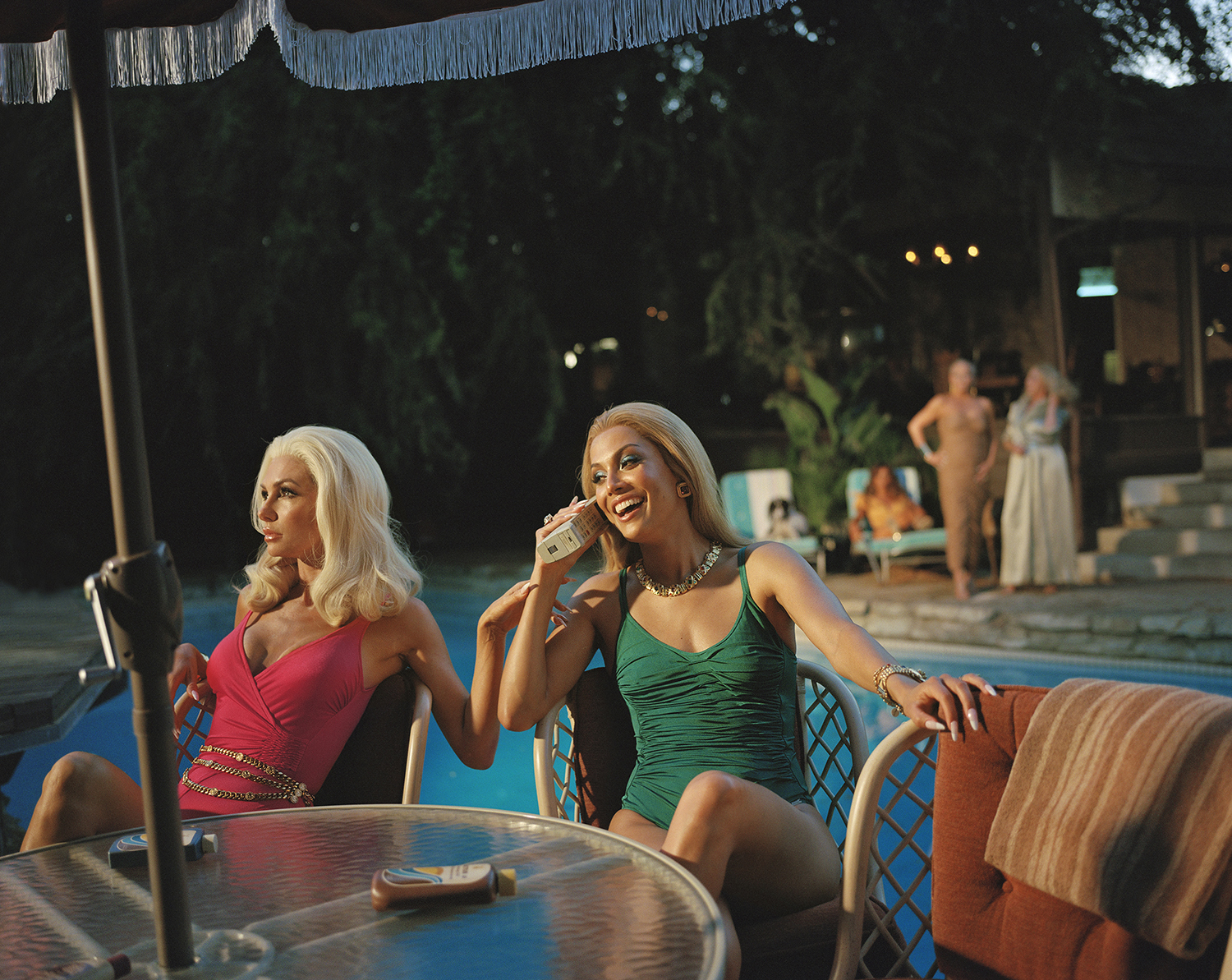

In fact, the only time Cohen isn’t careful is with her creative output. Upon completing her photography degree at the London College of Fashion, she relocated to California not to proximate to the world’s A-list, but to acclimatize to the distinct blend of glitz and grit unique to the state — both elements that distinguish Cohen’s style. Her visuals are low-brow and lush: swampy depictions of relatable scenes staged beyond recognition; hedonistic-hued portraits of the human condition that perspire debauchery, always alluding to all seven deadly sins with unwavering consistency. The result is somehow repulsive and compelling all at once — like a bad wax reproduction of Paris Hilton. And just like Paris, it’s all emphatically ‘Made in America’.

Thus, instead of stargazing, the photographer’s fascination with Americana meant that her early days in LA were spent stalking the city streets at night to shoot without a permit, or taking long road trips with pit stops at gas stations and 99 cent stores to document the ‘American Worker’. One particular expedition saw her enter a meth den and inexplicably kicked out of a moving car, after advertising for subjects on Craigslist — a testament to the lengths she will go to spotlight unseen America, and it’s underbelly.

“I loved street casting,” she explains. “It was, ‘Who can I get to shoot? That person looks interesting…’ I was never really trying to seek out jobs in the entertainment industry, making music videos or shooting anyone famous.”

Citing Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing’s comfort in “comically distorting, or even in some cases altering, images to the point of the grotesque” as primary inspirations, Cohen soon transitioned into self-portraits — transforming into various characters fashioned from the mementos she’d found on the road for one of her most well-known projects, the pointedly probing and monstrously camp, Name Tag.

“The idea was very personal to me as it was my perception of who these people were,” Cohen says. “I thought it would be more interesting to have one person interpret and physically embody these characters — so I did it myself.”

Consequently, everyone knows Nadia Lee Cohen’s face and no one does. The photographer has taken many, many selfies, but she’s rarely without wigs or prosthetics. With a light scroll you can see her cosplay jailbirds, judges and nuns, her work splashed across top-tier publications. It grates Cohen’s modeling agency, Wilhelmina, that the photographer has very few images of her looking, well, normal, but she’s just never found natural headshots as “fun”.

“It’s really flattering when people want me in front of the camera, and it’s important to know what it feels like,” Cohen shares of modeling. “But I also think you have to be comfortable to show yourself, and doing those projects makes me feel more comfortable. Spending time in front of the camera also encourages me to be more sympathetic to subjects when I am behind it.”

With production at a standstill due to coronavirus, Cohen has had little choice but to become her own muse. It’s been frustrating to maintain audience engagement with increasingly personal photos, without flooding out her professional work from her feed. Then there’s the added pressure of her still untitled first book arriving later this year. It’s a compilation of images spanning the course of Cohen’s career, which mandates many of her archival photos go unpublished on social media or news outlets. This marks the first time the project has been officially announced (and some of the photos shared), and while originally slated for a summer release, the book has been indefinitely pushed back due to the pandemic — only limiting the photographer further in what she can share with fans.

“A lot of my friends complain about their work not getting as much attention as a selfie,” laughs Cohen. “I think people tend to feel more of a connection to the person from seeing a low resolution, iPhone image of them — it feels as though they are witnessing reality rather than something curated.”

Nevertheless, quarantine itself has treated the creative well. Despite only recently dipping her toes in filmmaking (the ‘pig police’ theme of A$AP Rocky’s “Babushka Boi,” directed by Cohen, recently recirculated on social media as a symbol for law enforcement ineptitude in the ongoing fight against police brutality) she’s been working on a feature concept for several years. FOMO-free due to mandated social distancing and weeding through years of ideas, Cohen’s script is fast-tracking. Still, a sidestep into the film industry was more “hope” than plan.

“When I first started making videos it was almost a test to prove to myself I could make my photographs move and it’d be enjoyable to watch,” she says, adding that she’s now shifted her process of conceptualizing projects from visual cues. “[Now] I’ve been thinking about the story in a narrative way, not a visual way. It feels unfamiliar, yet exciting.”

Right now, the battle is maintaining focus. Cohen knows too well Instagram can suck you into a vortex of color and self-comparison, and approaches the app with only the utmost trepidation. Nonetheless, her relationship with social media seems relatively healthy. In fact, she finds Instagram’s subtle inauthenticity “comforting” — a stark contrast to the well-documented anxiety most women experience interacting with the platform. To Cohen it’s a casting goldmine: if she requests a “man with a round, hard belly” for a subject, one will be procured through her direct messages in ten minutes flat. She also counts herself lucky that her followers are there for her work first — whether or not it features the photographer in it.

Hence why she so deeply values her leagues of disciples. Subscribing to Nadia Lee Cohen’s universe is to embrace her perversely glamorous alternate reality, with triple-breasted women and satanic television personalities all in technicolor. She might cast a gaggle of middle-aged playmates to actualize the Valley Of The Dolls’ men-less utopia of her dreams (for the last ever winter issue of Playboy) one moment, and make out with Danny Trejo the next. As such, her professional fantasy is not necessarily the praise of Scorsese, but merely the industry’s price of admission: a full cinema, there just for her. When you extract the extraordinary from the American everyday, it’s the reaction of the ‘every man’ that means the most.

“There’s certainly people I admire and their opinion of my work would matter to me,” she concludes thoughtfully. “But I think I’d always imagine showing something to an audience… just a room full of people watching something I’ve made.”