“Art History taught me there’s only two types of women,” said Australian queer comic Hannah Gadbsy, in her poignant Netflix stand-up special Nanette: “a virgin, or a whore.” The Art History graduate-turned-comedian goes on to condemn western society’s unwillingness to recognize that high art has relied on a glorification of the patriarchal gaze, at the expense of other narratives. Maybe it’s time we listen.

In California, the recent group exhibition Everyday Muse at ltd los angeles gathered some 20 contemporary visual artists, invested in the reconfiguration of the artist-subject dynamic. “The muse is such a romantic idea,” says photographer John Edmonds, co-curator of the show, which includes works by Mickalene Thomas, Lyle Ashton Harris, Vaginal Davis, and Elle Pérez. “We wanted to push the idea of how active a muse can be for an artist.” And the title alone says it all. There is, traditionally, nothing mundane about the muse — a goddess-like figure, originating from Greek mythology and inspiring artists to reach divine creative heights. Celebrating our everyday muses becomes somewhat of a political task.

Yet the muse was never exactly passive either, far from it. According to feminist thinker Germaine Greer (recently criticized for her trans-exclusionary views), the muse’s role is “to penetrate the mind rather than to have her body penetrated,” suggesting a reversal of agency, grounded in gender and sexual politics — perhaps even transcending the virgin/whore binary (shock!) But is such reversal sufficient to shift the patriarchal gaze, or does it merely validate the entitlement to spontaneous creativity granted to male artists for centuries?

“The idea of a muse, to me, makes art unintellectual,” LA-based artist Chanel Von Habsburg-Lothringen tells i-D as we walk through the exhibition, in which her work is featured. “It makes it this thing that is divinely inspired. That’s probably why I have such a beef with the muse.”

Working with sophisticated photo collages that speak to the female experience and social-class fantasies, the 29-year-old artist often inserts fictionalized versions of herself into her work — celebrating a recent legacy of self-portraiture shaped by the likes of Cindy Sherman or Linder Sterling.

“I was thinking about the performance of class,” the artist explains of her photo collage, in which she appears amidst a constructed Hollywood scenery, donning a hat at once glamorous and peasant-like (think Courbet’s Stonebreakers, she jokes), while floating hands are serving a surrealist American-West: corn nuts and beef jerky. “We take on certain material possessions in order to announce ourselves as something that we’re not,” she continues, “and how these cracks and fissures in the reality play out.”

Throughout the show, other examples of self-portraiture bring attention to the self as muse. An early work by Mickalene Thomas — known for including family members, friends, and lovers in her paintings and photographs, often elevating the black female form in ways that subvert art historical canons — shows the artist in a blonde wig and campy makeup, inside a cryptic, steel environment, possibly a corporate office elevator.

Meanwhile, a seemingly nostalgic self-portrait of Lyle Ashton Harris shows the photographer at the 1989 San Francisco Gay Parade. “I was experimenting with ways of seeing, in essence, becoming my own muse,” explains the photographer. “In this moment, relaxed, youthful, joyous, among friends,” he continues. Despite that impression of insouciance, the bleakness of the AIDS epidemic lingers in the contextual narrative of the work, creating tension between the personal and the political.

The self as muse continues its dialogue with queer politics in the work of Mexican painter Ana Segovia, with a self-portrait of the artist in a t-shirt that reads FAG in bold letters — addressing her fantasised trans masculinity. Fellow Mexican queer artist Manuel Solano shows two videos separated by 20 years, and radically differing social realities. The first one, a personal archive film from 1994 — the year that NAFTA came into force, profoundly reshaping North American consciousness — shows the artist celebrating their sixth birthday, in a middle-class Mexican home where “Happy Birthday” is sung in English, and Nintendo video games are gifted.

The second, from 2014, shows Solano performing a mock catwalk in front of their computer’s camera. As they slowly take off layers of dark clothing against a domestic backdrop, lesions are revealed across the artist’s body and face, while they start sobbing uncontrollably. The wounds, are the result of an untreated HIV-related infection, which eventually made Solano clinically blind. As opposed to the first video, which renders the Mexican middle-class assimilation to a North American fantasy, the second, reveals the cracks of a broken dream — the country’s inability to comply with basic human rights and healthcare access. It also offers a variation of the paradigm of the muse — in which the wounded, imperfect, queer body is elevated through personal trauma.

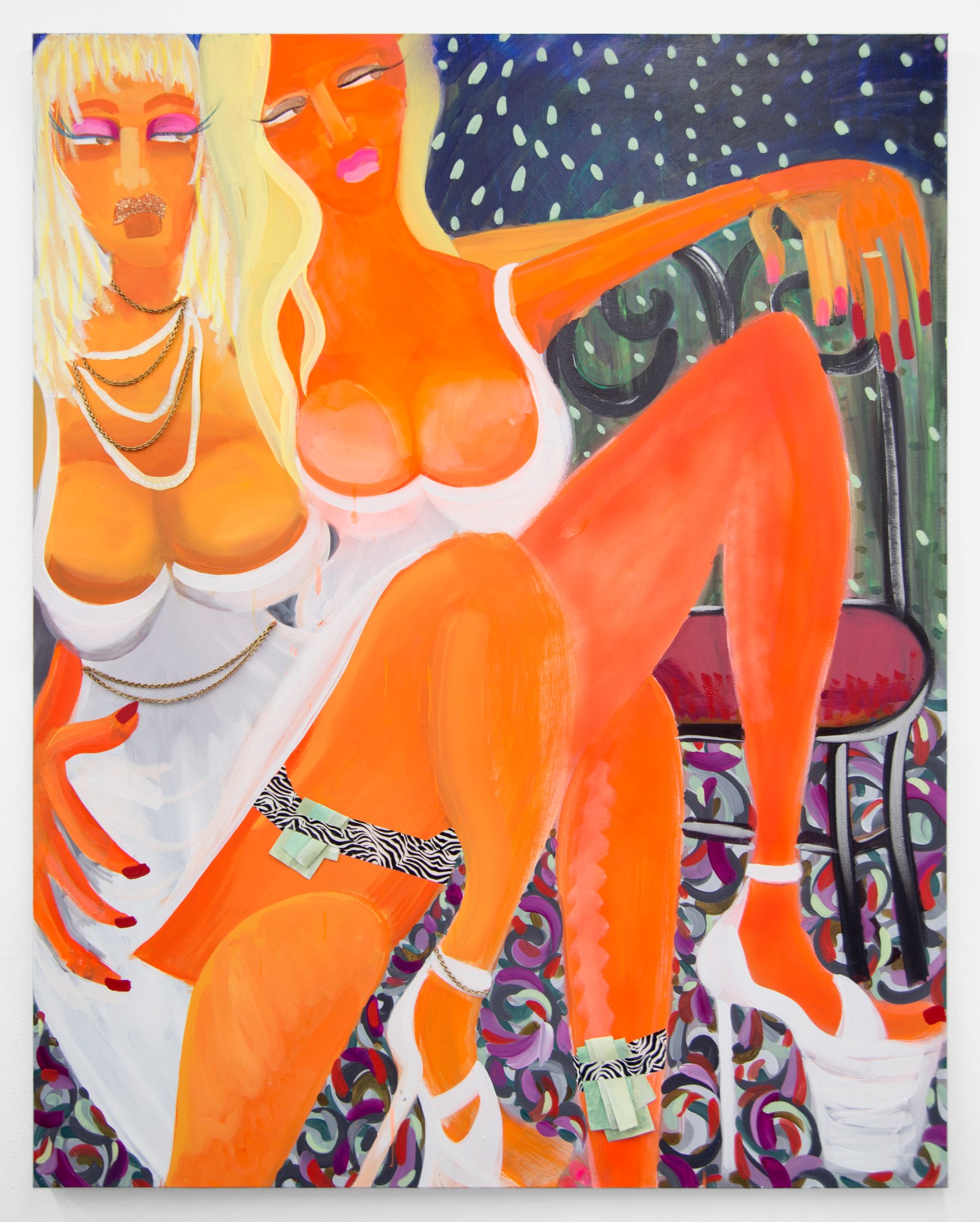

But let’s go back to the virgins and the whores for a minute. In the work of Chicago-born artist Chelsea Culprit, the figure of the fallen woman is reclaimed from the male gaze à la Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Manet’s Olympia, or even Degas’ often misunderstood ballerinas. Herself a former strip-club dancer, Culprit positions sex work as a central narrative in her work, which spans painting and sculpture. In the exhibition, the women in Culprit’s two paintings are her former co-workers, depicted in moments of intimacy, at once comical and profoundly existential. The mode of representation, emerging directly from the subjectivity of the artist’s experience, shambles the historical canon. The dancer, the virgin, the muse, and the whore — perhaps fictitious categories after all, carefully crafted by those who best benefit from them.

How many muses does it take to build the success of an artist, and who gets to dictate the worth of their labor? Coincidentally, the exhibition Everyday Muse finished the same week as a #MeToo-inspired protest group stormed the Warsaw exhibition of Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, in solidarity with his long-time muse Kaori, following claims of emotional abuse. We have centuries of dominant narratives to rectify. Now the conversation burns hot, and requires our full attention. As Gadbsy noted of Picasso, master of misogyny, and his underage model-turned-mistress-turned-wife, Marie-Thérèse Walter: “Our mistake was to invalidate a 17-year-old, because we believed her potential was never going to equal his.