While en route to the beautiful city of Kigali for the Rwandan Collective Fashion Week, I made a pit stop in Nairobi, Kenya to chase down the Maasai market. The market itself is almost as nomadic as the actual tribe, moving around the capital from day to day with its overwhelming spread of beautiful Kenyan Maasai plaid fabrics. In the eight hours I spent in Nairobi, I motorbiked all over the city, one end to the other, and saw the pattern everywhere. When my eight hours in Nairobi came to an end, I hopped on our 737 out of Jomo Kenyatta Airport and woke up in Rwanda. As we drove around Kigali I noticed I was still seeing plaid — different colors and variations but still plaid, everywhere. I considered how the geographical proximity of the two countries inevitably could have created a trend in both cities. By plane, Nairobi and Kigali were only an hour apart. I then considered the other side of the continent where I was from, and realized West Africa had a history with the print as well. Even with this knowledge, as a Nigerian-American when I thought of plaid I thought of 90s grunge culture in London, not my grandfather’s waist wrap that he’d been wearing since the ‘30s. How did this western print permeate two opposite ends of the African continent at such a traditional level?

One of the earliest traces of plaid in West Africa dates as far back as the 17th century and is a product of British colonialism. The “lungi” or “madras” was a plaid fabric worn in south India that made its way, through trade, to southeastern Nigeria where it became known as “george” to the Igbo tribe and “injiri” to the Kalabari people. It became a prized cultural heirloom to both peoples.

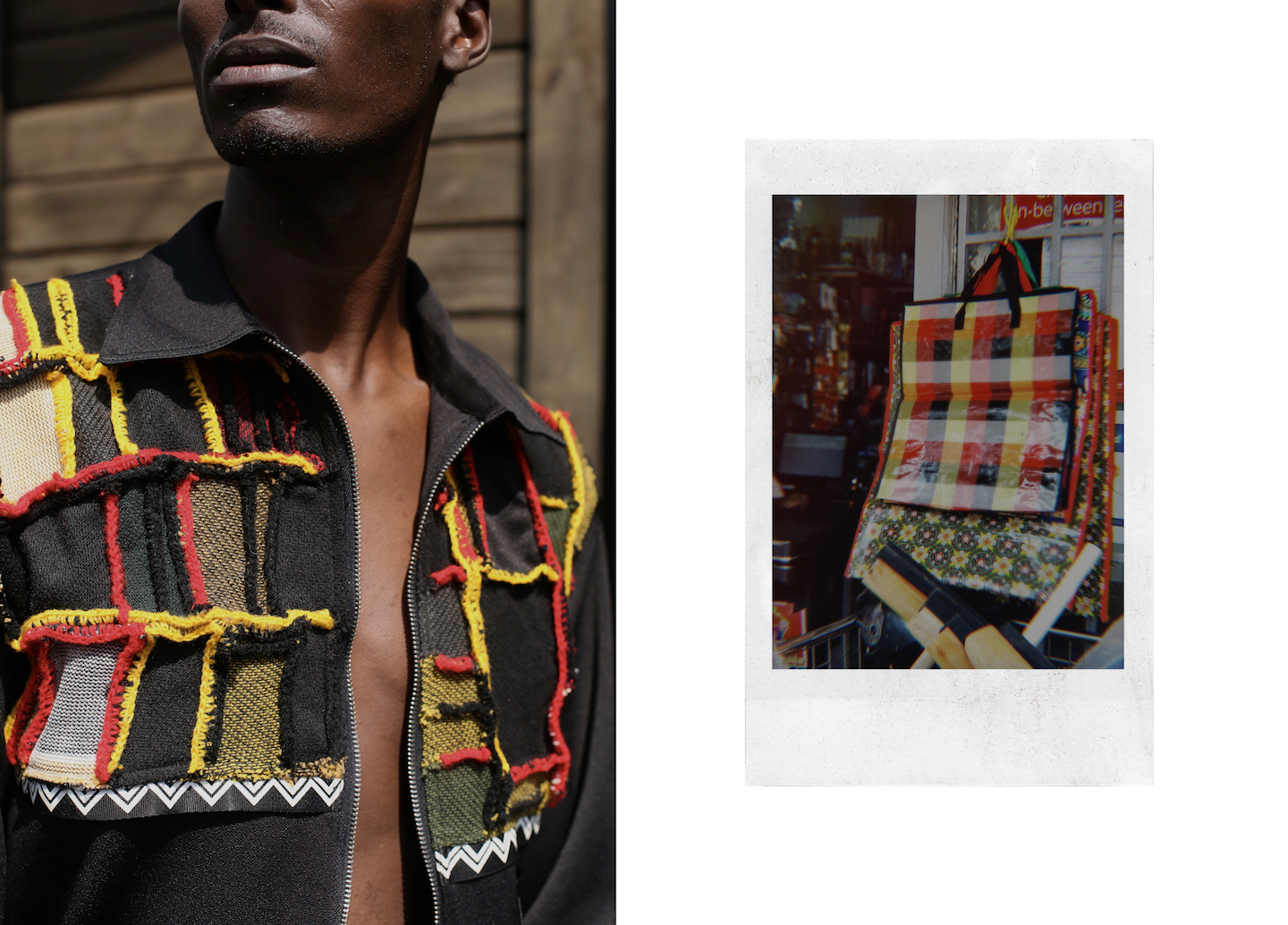

Centuries later on the same side of the continent, strife between Nigeria and Ghana made way for the rise of one of the most popular plaids in sub-Saharan Africa: The “Efiewura Sua Me” or “Ghana Must Go.” “Efiewura Sua Me” literally means “help me carry my bag” as the plaid was famously used for large bags that were perfect for hauling large quantities of lord-knows-what out of local markets. But before it got its comical name it was known as the “Ghana Must Go,” and was a symbol of the estranged relationship between the two countries. In 1983, over 2 million West African immigrants who had fled to oil-rich Nigeria in the ‘70s were expelled from the country after the oil industry crashed. The immigrants were given two weeks to leave, lest they be thrown in jail. Those two million immigrants packed their belongings into red,white, and blue plaid bags and made the journey out of Nigeria, often in brutal conditions. Many of these expelled immigrants were Ghanaian, giving the bag and synonymous plaid fabric its name.

With south India’s “lungi” turned southeast Nigerian “george,” the “Ghana Must Go” pattern that narrates a history of displacement in West Africa, and East Africa’s undying love for Masaai shukas, plaid has crossed cultures and borders alike, redefining what exactly constitutes “African Print.” We got together some of the Africa’s most studied creatives to discuss the history of plaid on the continent and how it’s come into play in the diaspora today.

Moses Turahirwa, Designer of Moshions, Rwanda

“Our plaid pieces draw inspiration from all over the world, but most especially in East Africa. The playful blend of colours and light threads capture our bold creativity, and pays homage to this cultural fabric.”

Adebayo Oke-Lawal, Designer of Orange Culture, Nigeria

“I wanted to create corsets that reminded me of iros and the plaid complemented the prints I worked with nicely. I like infusing things from different parts of Africa as well, and plaid always connected me to my trip to Kenya a few months before the release of my collection. It felt like an amalgamation of Nigerian and Kenyan culture and the beauty of both working together.”

Chiadikobi Nwaubani, Editor of Blog/IG page: @Ukpuru, Nigeria

“The lungi is a plaid material, commonly known as madras, is a textile from India that has become ethnic wear in southeastern Nigeria, known as George (Jịọjị) by the Igbo and injiri by the Kalabari.”

“The Kalabari used injiri to cover ancestral shrines and the cloth is so meaningful that mothers are gifted with a piece after birth. The Igbo tie George on ancestral figures, some masquerades, and wear it for festivals. It is a prized heir loom in both cultures.”

Chioma Obiegu, Designer, Ghana

“I felt the need to bring back a piece of clothing that instilled some kind of emotion or nostalgia, something timeless that told a story; other than trendy clothes that are momentary. I incorporated the history behind this specific plaid called “Ghana-Must-Go” in West Africa and how the name originated. This way, foreigners gain some insight about the plaid while locals are reminded of their history. Ultimately, blending style and fashion with history and storytelling.”

Matthew Rugambar, Designer of House of Tayo, Rwanda

“For this particular collection I was inspired by the nomadic herdsmen tribes across the continent, one of them being the Masaai. This particular plaid piece was inspired by the Masaai. While the Masaai are more concentrated in Kenya and Tanzania, they travel throughout the region almost as if the borders don’t exist.”

Sunny Dolat, Photographer & Creative Director, Kenya

“In Africa, plaid has become undoubtedly synonymous with the Masai. How exactly the previously hide wearing Masai switched over to the ‘shuka’ and how they obtained it is still a topic of rigorous debate; was it via the Scottish missionaries, as some say? Or was it through the daily ins and outs of trade? We can’t however deny that plaid comfortably found a home with the Masai and has over the years become one of Africa’s most recognizable textiles.”