On 4 December 2017, 20 teenage boys from the extreme-security unit of a Juvenile Hall in California staged a fashion show. Taking place in the exercise yard of their detention facility in Orange County, the boys took turns walking designs of their own creation while watched by a 150-strong crowd of judges, family members, officers and volunteers. It was an event that could have ramifications beyond the confines of this unit, in a country whose correction system has long been focused more on retribution than rehabilitation.

Crystal Anthony is a therapist at the centre. “You have to be very real talk, to the point and authentic,” she explains. “My kids can tell when people care and when they don’t.”

Focusing on compassion-based therapy, she began working with Extreme Security Risk (XSR) youth — those that are considered the ‘most dangerous, highest risk or highest level of criminal sophistication’. Many are being charged as adults due to the severity or violent nature of their crimes and some are facing life imprisonment. They range in age from late teens to as young as 14, and come mostly from communities in the Orange County area.

Crystal explains it’s all about providing space that allows people to see themselves as ‘someone of worth’. “We started bringing in artists, speakers and community organisations that were experts in gang prevention and had lived in that life,” she says. “It’s nothing new in itself, it’s just about doing it.”

Richard Cabral, an actor in the biker television series Mayans MC, and a former gang member, came in to read his poetry. “He understood, and didn’t just come in one time,” she says. “He has continuously dedicated time to help them with their poetry. My kids love him and he’s been a true inspiration to a lot of them.”

Little by little, she and the others around her kept trying to think of new things they could do. Around this time, the photographer James Mooney, who had been introduced to Crystal by Richard, then introduced her to Mari Tibbetts, a clothing designer for sportswear company ASICS. “We ended up meeting for coffee and I was like, ‘A lot of my kids want to be designers. It’d be fun if we could do a little fashion show’,” says Crystal.

Mari came to the US from Japan hoping to be a tennis player but became a designer instead. “It’s a different road,” she says, “but I can’t complain.”

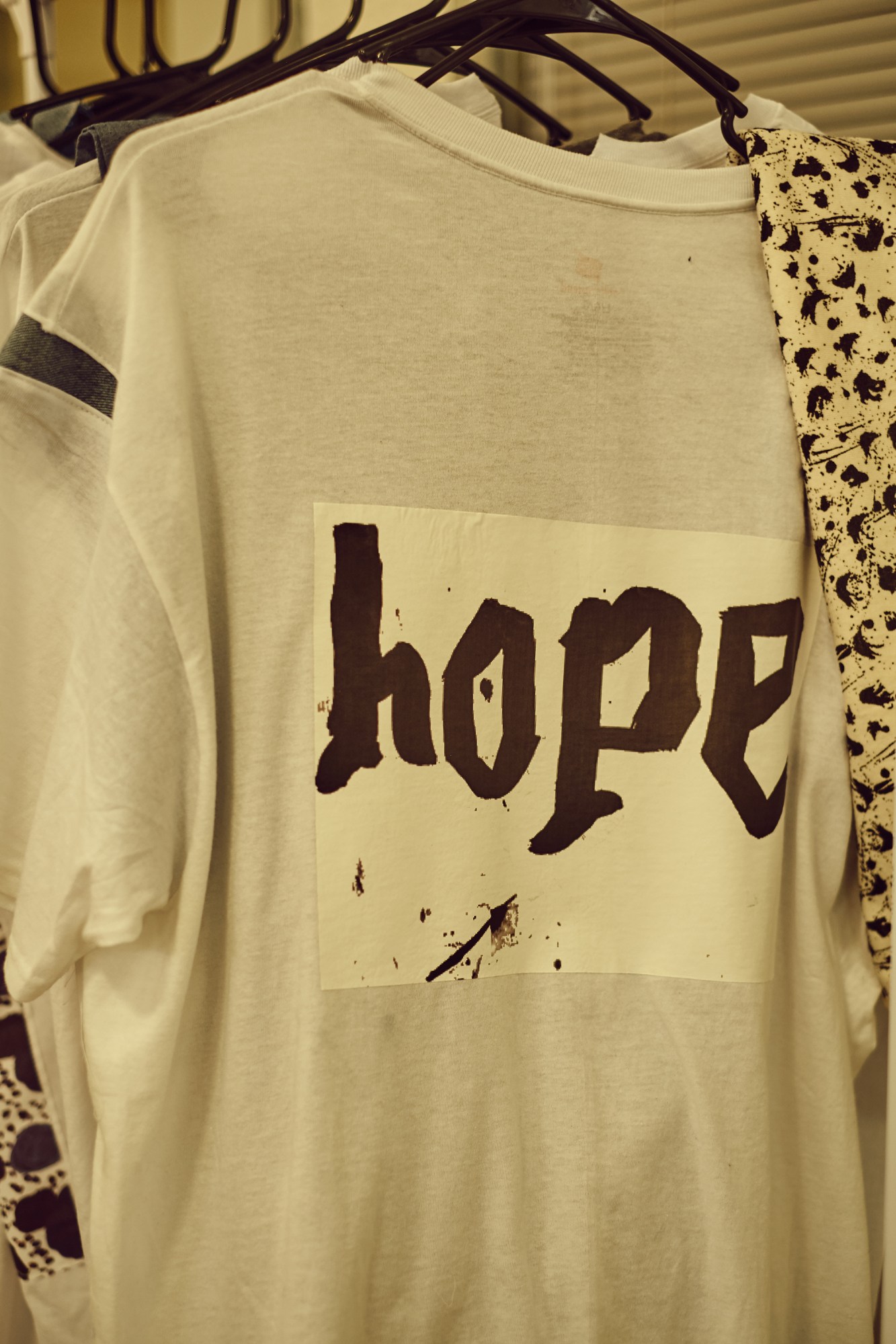

She started to get to know the boys at Orange County and trying out different techniques. “I went in with all those tools,” she says. “When I showed Japanese calligraphy with ink and brush, they gravitated toward that right away.” They created hundreds of artworks, while Mari taught them how to make traditional sumi ink from scratch, scraping from a black rock and adding water.

The young people started to trust her and told their stories. “I believe kids are not born as murderers,” she says. “Somehow, our society failed them and they’re in the situation they’re in. One kid opened up to me about losing his mum, how he was evicted from their apartment, and nobody picked him up. He wasn’t put into a home or anything — he was literally evicted to the street. 13 years old. He had nowhere to go. No food. No place. And he ended up with a gang member. They became family to him.”

After two weeks of talking, painting, printing and sewing, the day itself came. “Taking these 20 boys’ artwork and putting it on to 20 outfits was a very emotional process,” she says. “It was such an emotional roller-coaster, and I think it’s because I could feel every artwork representing each kid’s story. Once I had the outfits in a suitcase, bringing it to California, it was like I was carrying a newborn baby. I didn’t want anybody to touch it. When I brought it into the Hall, I was literally shaking. I didn’t know how they were going to react, I was very scared and nervous.”

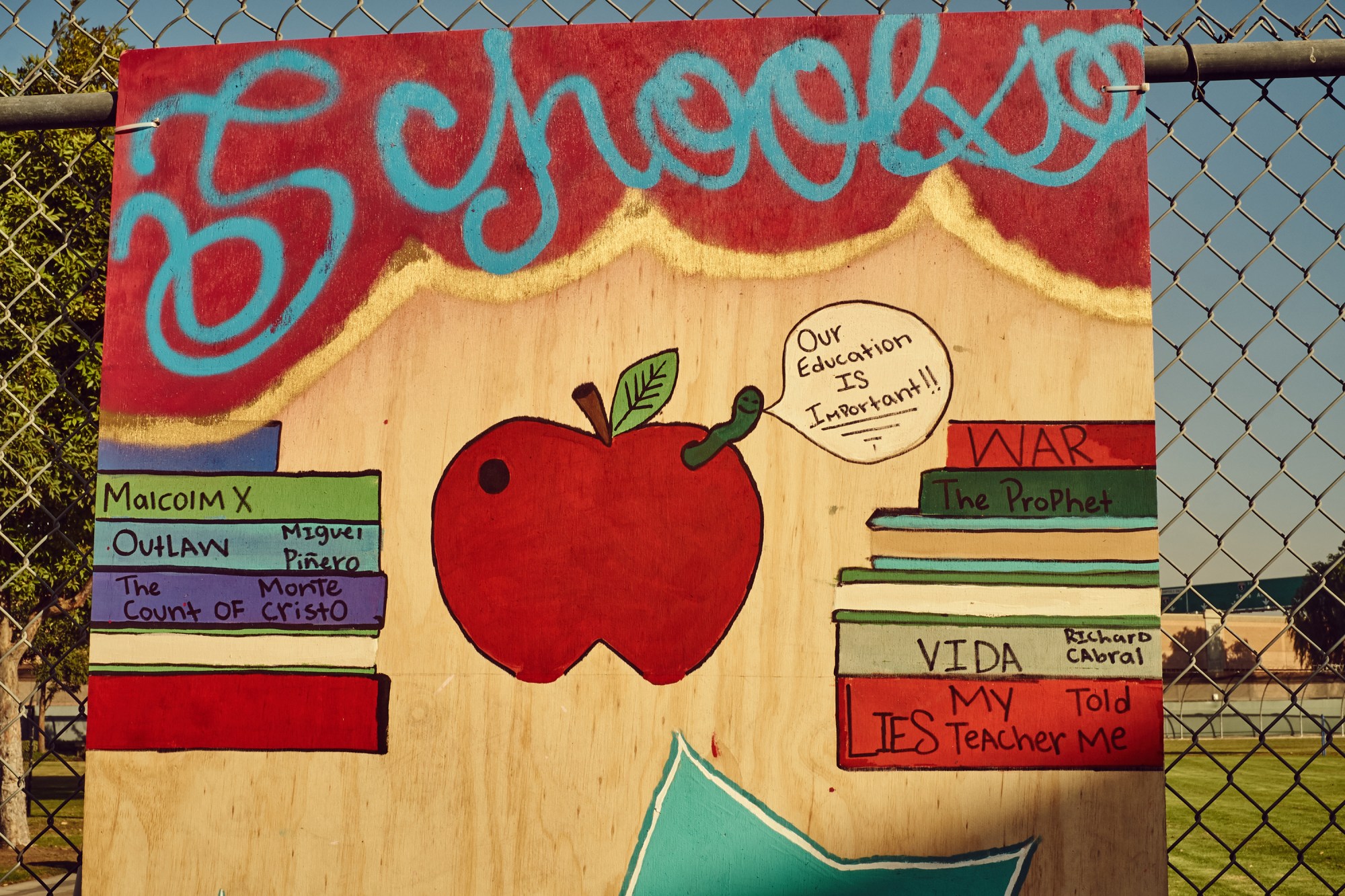

The boys weren’t comfortable at first, refusing to wear v-necks, scarves or anything with pink. “It was hard for me to get them out their comfort zone,” she says. “Then, I noticed their demeanour change, and they were just nervous. We had about 150 people in the audience… Family members, visitors, judges, directors.” Big murals of artwork painted on wood and portraits of the young people hung on the walls, so they could be seen by everyone walking into the unit.

“The mood was dark, at first,” continues Mari. “Having a show within the Hall was unusual. Even family don’t get to come into their kids’ territory. People were also scared, you know. The boys were free and walking around. Anything could happen.”

The young man who was set to go first had an attack of nerves, and said he couldn’t do it. “But the moment he stood on the beginning of the runway, and saw everybody in standing ovation and clapping, I couldn’t stop him,” says Mari. “He walked out on the runway so fast, so proud and was over the moon. And from there, the show was not long, but it was really amazing. Goosebumps. People standing up and cheering and screaming. And each one of the boys felt that to their heart.”

Among the audience were supervisors handling the boys’ cases. “They were so impressed,” Mari says. “The Director of Juvenile Hall was there with the judge, who was also amazed. They couldn’t believe how good they looked, and what they had put together.”

“One of our main goals here in Juvenile Hall is to restore the humanity of our youth,” says Erick Bieger, Supervising Juvenile Correctional Officer of Orange County. “Throughout the process of the fashion show, our youth were able to tap into their creative potential and discover they’re so much more than they previously thought. They were able to see past assigned labels of ‘criminal’, ‘gang member’, and ‘worthless’, and began to write their own labels — ‘intelligent’, ‘dreamer’, ‘redeemed’.”

Crystal believes it’s important to see the fashion show in the context of the work they have done to shift the culture towards one of trust and compassion. “At the end of the day, how does change continue to happen after the fashion show’s done? Rapport-building and relationships. We have many groups in the unit from rival gangs that worked together… Those changes were all happening before the fashion show.”

And Mari says there have already been lasting effects from the event. “One of the kids from that show is now on house arrest, so he’s out,” she says. “He has a little daughter and gets to see her. One of the kids was going to be sent to adult jail but now his case is being re-visited.”

The day following the show, Crystal walked into the unit and it was silent. “The kids were quiet, and I was like ‘What’s going on?’” she says. “I don’t know how many times I told them I was proud of them, like, ‘You guys are so freaking rad!’ And their eyes perked up, and they were like, ‘We had so much fun! This was the best day of my life.’ How cool is that?”

Other Juvenile Halls have got in touch to see if the success can be replicated and Mari and Crystal are already putting plans together for a follow-up: “Bigger scale and more elevated,” Mari says. “Hopefully, we can include girls, too.”

Things will take time, of course — an entire correctional system does not change its hardline approach overnight towards one of compassion and rehabilitation. “As we eradicate this antiquated and harmful mindset and replace it with programs steeped in restorative justice we’re finding our youth regain their sense of self-worth and are at a much lower risk of recidivism after release,” says Erick. “In the end, isn’t that what we want?”

“One of my kids started doing college courses and had to pick somebody who’d inspired him, and he happened to pick me,” adds Crystal. “He said, ‘I wish I’d met you before I came in here, because maybe I wouldn’t have come here.’ I think that’s the thing. People forget: it only takes one person to believe in somebody for change to happen. All it takes is one person to say, ‘You are somebody. You are worthy. You are lovable.’ That’s all it takes. Can you imagine if each of us was a person for somebody? How different this world would be.”

Roderick Stanley is founder of Good Trouble, a publication about the intersection of arts and activism. You can read more about Orange County Juvenile Hall here.

Credits

Photography James Mooney