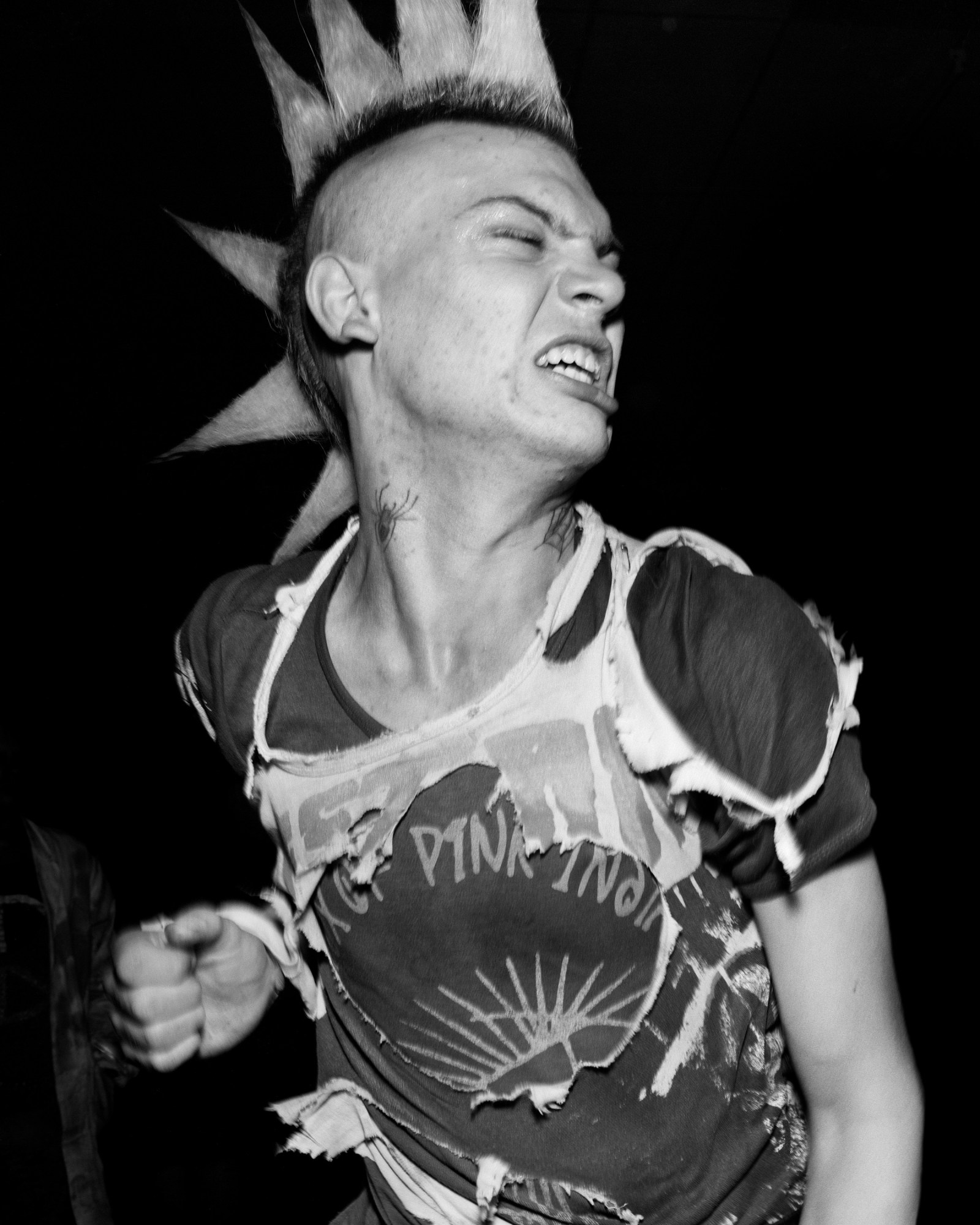

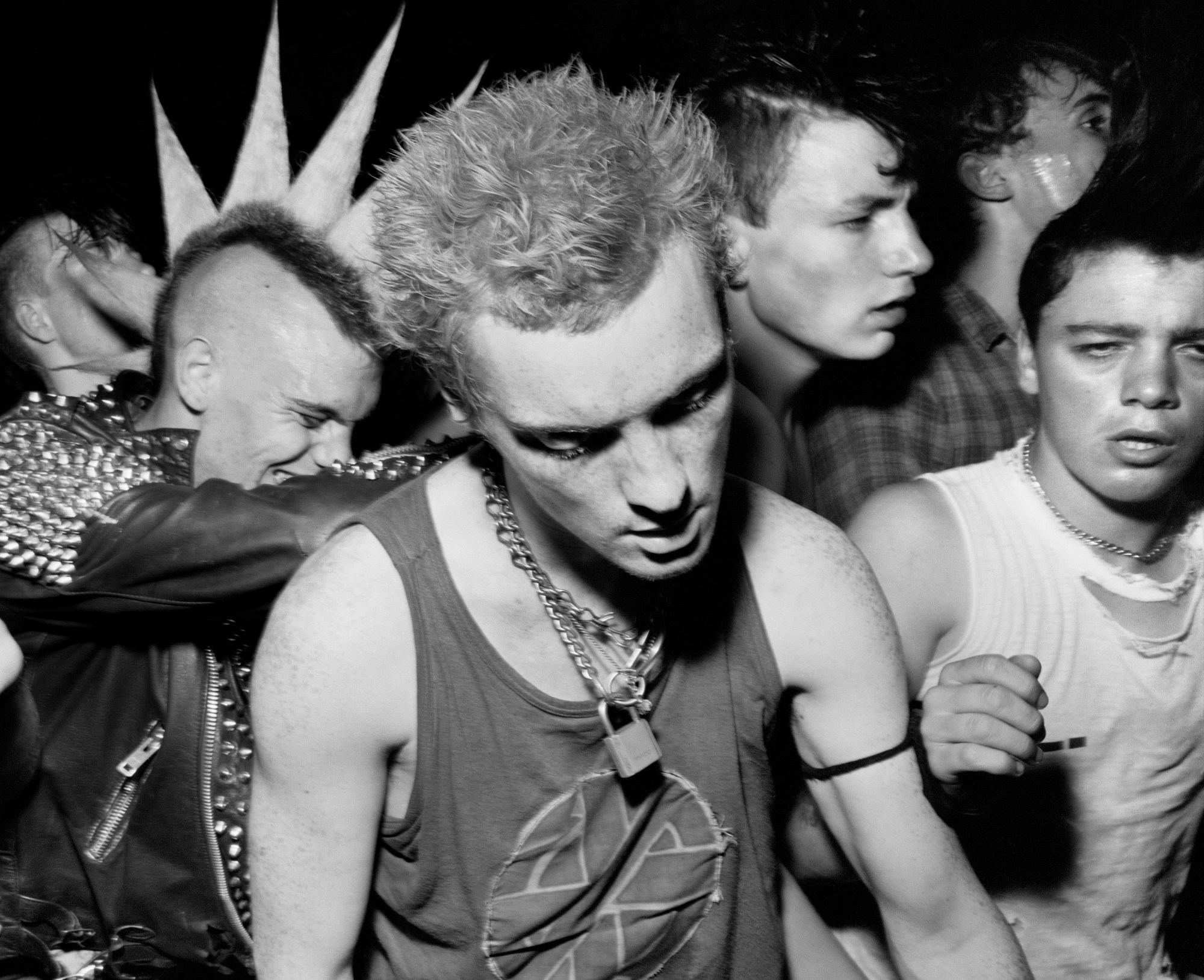

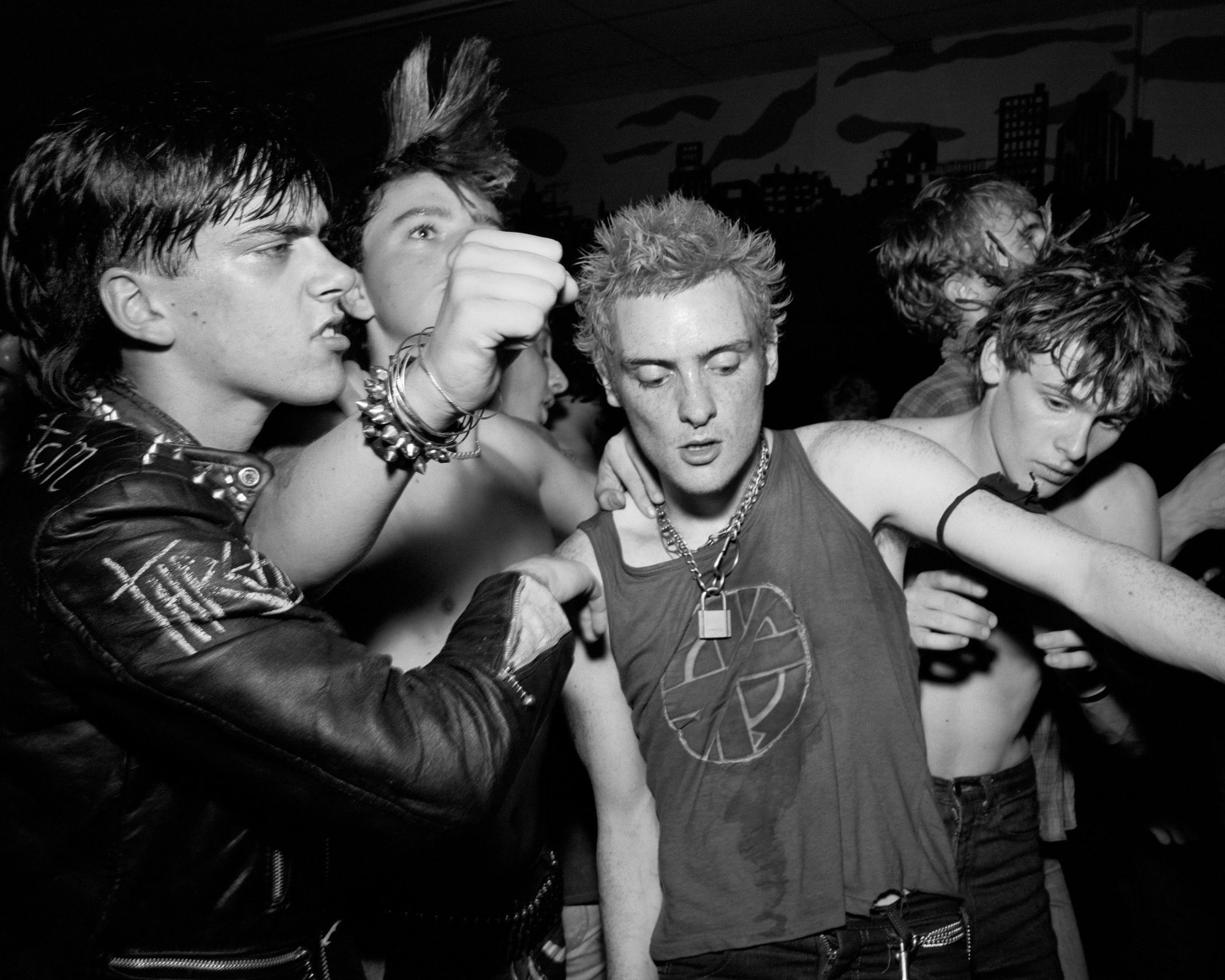

There’s a sequence of photographs from Chris Killip’s new book The Station that feature a young blonde man with spiky hair, wearing an anarchist punk tank top and a chunky chain necklace locked together with a padlock. The series has been designed to look like a film strip, as if the photographs were all taken on the same night, but from the slight nuances of his hairstyle — more gel, a little crimping — Killip knows they were actually shot on three separate evenings at the legendary northern club in Gateshead, where he spent many a Saturday night in 1985.

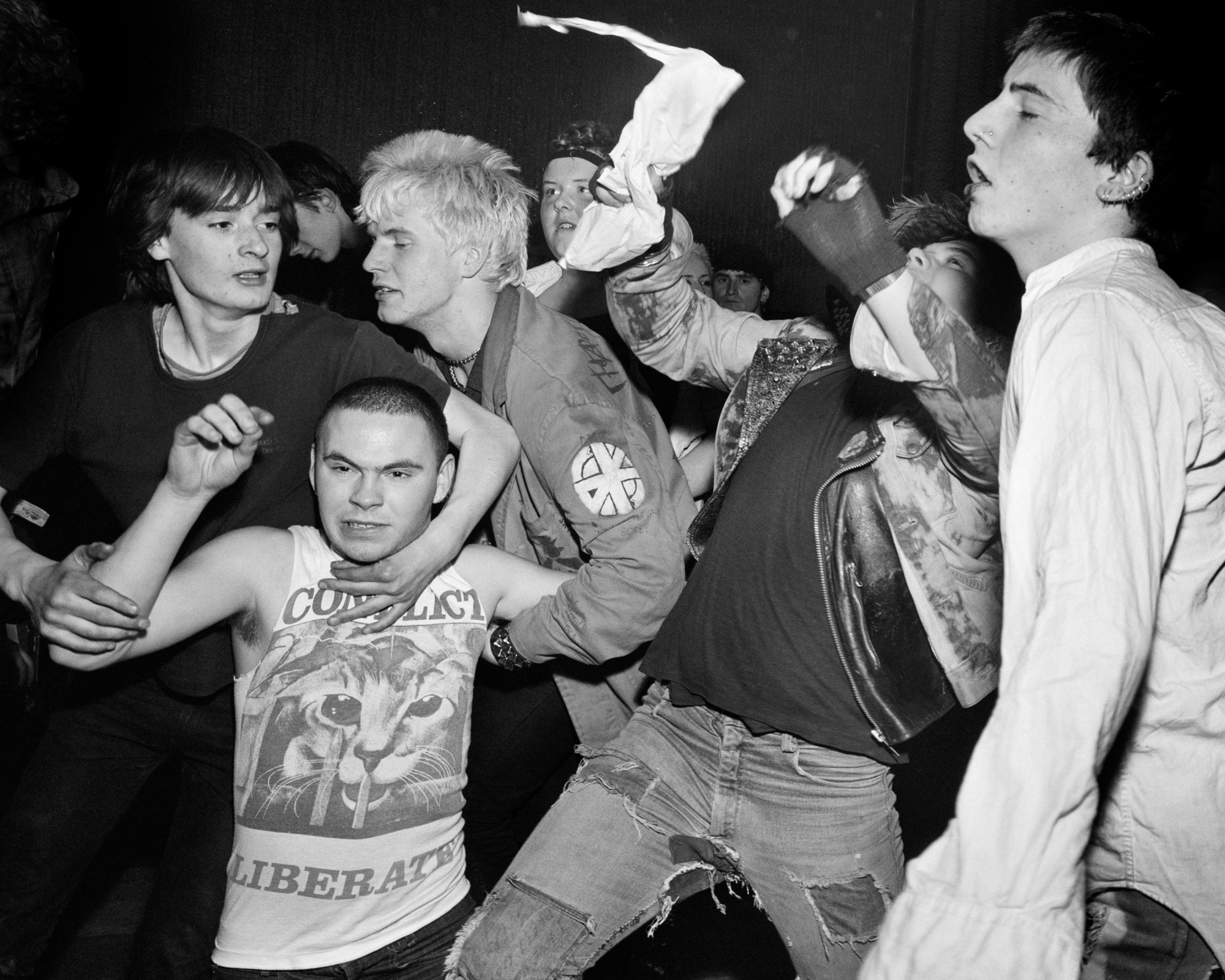

“They would come in exactly the same outfit week after week,” the photographer explains. “It didn’t vary because they didn’t have the money to perfect another outfit.” This was Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, after all, and youth unemployment was at an all-time high. The northeast of England was deindustrializing rapidly and mining, shipbuilding and steelwork industries had put a freeze on hiring, leaving working class communities without jobs. Many of the local punks who partied at The Station were at the miners’ strikes during the day, battling truncheon-wielding policemen, recruited from the south, on the picket lines.

Between March and October 1985, Killip visited The Station almost 20 times. Armed with a large Linhoff flatbed plate camera, a big American Norman flash head and a jacket with pockets large enough to carry his 4×5 inch slides. Killip describes his look as that of a newspaper man from the 50s or “a poor man’s imitation of Weegee the Famous.” Yet no one seemed to bat an eyelid at his eccentric attire. “I think that my oddness and my seriousness about it was enough somehow,” he says.

Inside, everything was painted matte black from the floors to the ceiling and walls. There was almost no light except for the one directed at the stage, and the music of bands like Sleep Creature and the Vampires, Hellbastard, Blasphemy, Conflict and Toxic Waste blasting from the speakers made it almost impossible for Killip to see and focus. “It was a phenomenal venue,” he says. Although Killip would leave exhausted with his ears ringing as he lay in his bed, the wild energy and strong sense of community that the club fostered made The Station so much more interesting than the other nightclubs in Newcastle at the time.

One that to its devoted pilgrims meant even more: “People felt the place belonged to them, it was their space… a celebration of their identity as punks,” Killip says. “[It] had a terrific importance, which I didn’t understand at the time as much as I do now.”

The Station was run by the left-leaning and politically active Gateshead Musicians Collective, who received money from The Prince’s Trust with the help of a man named Patrick Conway at the local library. It’s aim was to support new talent by giving them a space to rehearse in, and bring bands from around the world to play in Britain. In May 1985, they hosted The Clash — who were, of course, the original punk rock pioneers — for an impromptu gig, a bootleg recording of which still exists today. Tickets cost between 50p and £1.50, but for those that couldn’t afford it, an enduring passion for punk music would get you in the door.

The Station wasn’t a money-grabbing venture, but rather an arts collective with a core of 12 to 16 local creatives who met every Wednesday. “It was a place for outsiders, a place where weirdos could gather and no one would think you were weird. In that, it was a place where people could share like-minded ideas, share a vision and share a message,” says Malcolm Lewty, whose band Hellbastard emerged from The Station. “It was very unified; it was a very special place in many people’s hearts and it still is today.” That’s just the way his big brother Nigel Lewty had hoped it would be, when he founded the club in 1976 before the UK’s punk rock explosion.

By the time Chris Killip walked into the venue in the 80s, they were a highly organised institution rejecting any form of sexism, racism and bigotry. The anarcho-punk bands that played in the venue sang about the underdogs, the horrors of war, environmental damage, animal abuse and the dangers of capitalism. For punks aged between 18 and 24 in the Gateshead area, who embraced the idea of rebellion and anarchy but also wanted a community to latch onto while the outside world chewed theirs up — The Station became their escape.

One in which they could guzzle down cheap cider out of plastic flasks as they danced rowdily — skinheads, hippies, punks, Mods, rockers and the few teddy boys merging as one. Although there were no official bouncers on the door to throw people out, and a little bit of glue sniffing did take place, “people didn’t create much trouble because it was their place,” Killip says. “If someone was misbehaving someone would have had a word with them, but they wouldn’t have just thrown them out. They would treat people with respect.”

Killip’s documentary snapshots might have been lost forever, if it wasn’t for his son Matthew, a filmmaker and editor based in Brooklyn, New York. He discovered the photographs one afternoon, while looking through some old boxes in his father’s archive at Harvard University, where Killip taught for 30 years. One of Matthew’s favourite images from his father’s seminal book In Flagrante (1988), which captured communities in North East England suffering from de-industrialisation, was an image of a skinhead at The Station. He’s wearing a T-shirt that says “Conflict Liberate” above a caged tiger and looks like he’s falling down. “I love that picture, so to suddenly see more outtakes from that was pretty incredible,” Matthew says.

“I’m always interested in youth culture,” he adds. “So while my dad might be looking for the individual picture, more broadly the pictures are [about an] interesting scene that took place.” A lot of the photographs depict violent tussles, but for Matthew, the images that really stand out are the ones “where people just look like they’re in a completely different place,” he says. “There’s almost a meditative quality to their facial expressions, an ecstatic quality that really resonates with me and that sense of escapism. I’m interested in ways that people try to navigate or escape from the reality that they find themselves in. I feel like youth culture often has good solutions to that.”

Killip captures the energy and culture at The Station particularly well: “there’s a real clarity to how he photographs,” says Matthew. “A sort of hardness, and then if you look at them more there’s a tenderness underneath that.” It’s something that stems from the time and energy he devotes to the people, places and communities he shoots. When you live somewhere for a long time, you’re able to accept ambiguities that as a stranger you wouldn’t be able to see, Killip explains. “If you’re just around and part of the furniture, it becomes more interesting,” he adds. “You get closer to the subject, but it does take time and perseverance and it’s not always easy. You’ve got to persevere a little bit and also tell the truth.”

Originally from the rural town of Peele on the Isle of Man, Killip has always been surrounded by tight-knit communities. He grew up in the pubs his parents ran, which would bring locals together in the evenings. On Saturday nights, everyone from the greengrocer to the baker would sing and tell him all kinds of stories. “That affected my childhood, the sort of complications of life and how interesting it actually could be,” he says.

Since then, Killip’s worked as an apprentice to fashion photographer Adrian Flowers in London, returned to the Isle of Man to photograph the colourful characters of his hometown and spent 15 years living in Newcastle, during which time he photographed The Station and its raucous crowd. He resided in a caravan on Lynemouth Beach for over a year documenting the coal miners in Northumberland and at the Pirelli tyre factory at Burton-on-Trent — all these places have now disappeared. “I photographed what was around me and I became an historian by default, by just being there,” he says.

“In a sense, with photography you’re an historian because every time you take a photo that moment is gone. It will never come back. That’s always at the back of your brain, that this is history,” Killip explains. As a result, the photographs he takes are not really his at all, he says. But rather, they belong to the people in them. That’s why it feels so nice to be able to show photographs from The Station to those that were there in 1985, Killip says, to reaffirm their worth and that moment in time.

‘The Station’ will be on display at the Martin Parr Foundation in summer 2020.