“Turning 17 was amazing,” says Taofeek Abijako. On a rainy afternoon in the designer’s Tribeca showroom, we both reflect on what that age brought us. Me: a 2001 Toyota Corolla with crank-up windows and a tape deck. Him: an email from United Arrows — one of Japan’s leading luxury retailers — inquiring about his nascent menswear brand, Head of State+. The ink was barely dry on his Albany High School diploma when the shop picked up his entire collection.

Next week, Abijako will debut Head of State+’s fall/winter 18 offering at New York Fashion Week: Men’s. It’s his second season on the schedule even though not yet out of his teens.

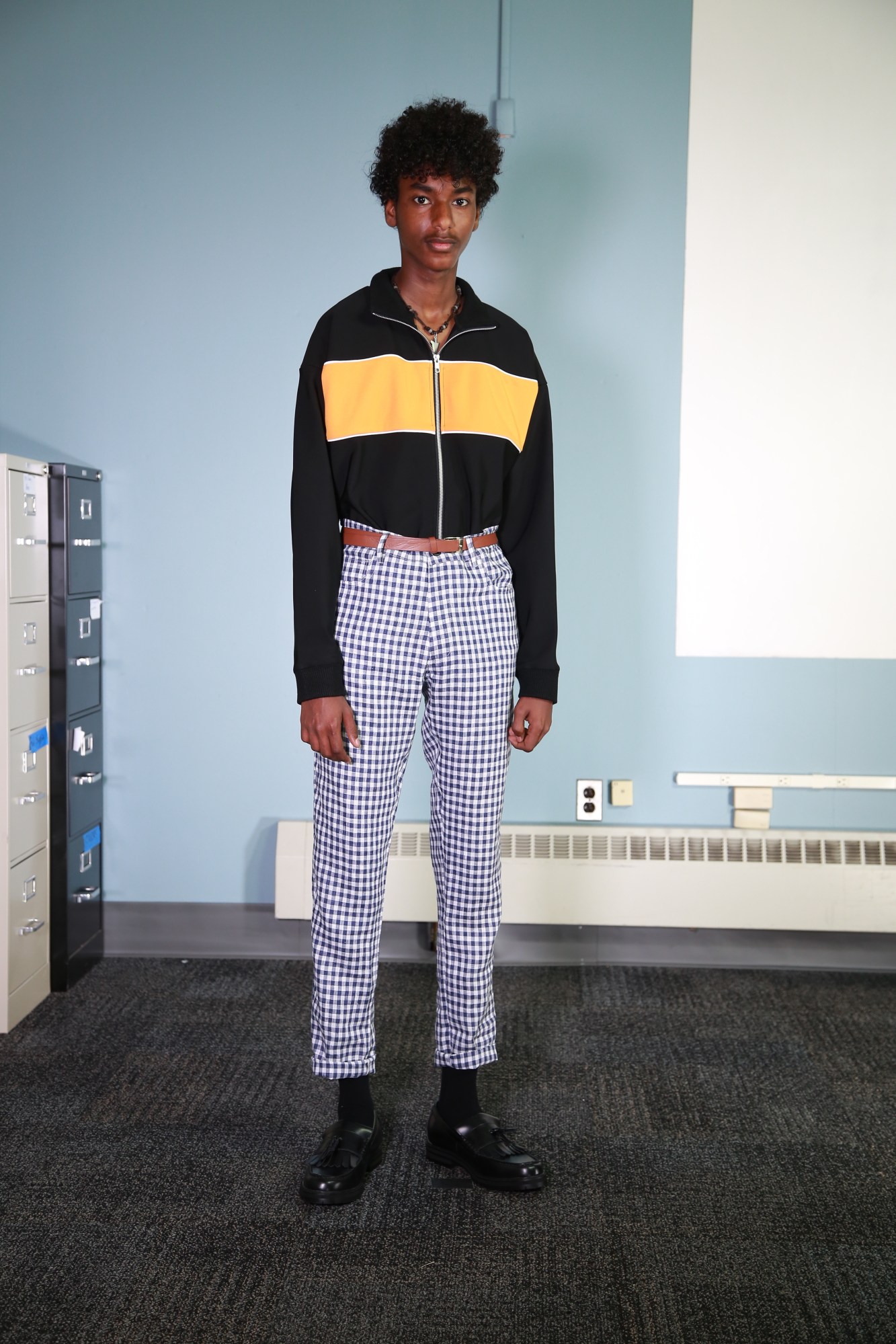

Like Abijako’s previous collections, “Brotherhood” is inspired by West African creativity and culture. The elegantly utilitarian range (think work jackets, slim-cut sweats) is shaped by Malick Sidibé and Sory Sanlé, photographers who chronicled the youth of Mali and Burkina Faso throughout the 1960s.

“I’m inspired by the sense of confidence,” Abijako says, scrolling through pages of black-and-white studio snaps. His favorite portrait features a teen in sharply tailored trousers and crisp white socks. “You’d think he owns the world,” Abijako beams. “In West Africa, regardless of financial difficulties and complicated social life, there’s a sense of joy in everything. You wake up in the morning fully ready to conquer the day. This image captures that feeling.”

Abijako was born in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. His father — also a fashion designer — won a U.S. Visa lottery in 2004. Before joining his father in Albany six years later, Abijako had never been to America. “It was extreme culture shock,” he explains. “Back in Nigeria, seven of us lived in one room. At night, when everyone wanted to go to bed, we lifted the table and laid a mat on the floor where we all slept. Imagine going from that to having your own bedroom, 24/7 electricity, and water. It made me appreciate things more.”

In that bedroom, Head of State+ was born. Abijako began raising funds for the project by hand-painting sneakers and selling them online. When Amandla Stenberg posted her pair of Abijako’s custom Vans on Instagram, sales picked up steadily. The two had met through As You Are, a film Abijako assisted on as a stylist. The film’s director, Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, is an alum of Youth FX, a creative empowerment program founded by Abijako’s high school pal Aden Suchak’s father. Suchak shoots Head of State+’s lookbooks.

Ahead of his NYFW: Men’s presentation, Abijako sounds off on connectivity, creativity, and confidence.

Your dad was a designer, too. What’s your earliest memory of fashion?

Visiting his studio on weekends, when I didn’t have school. I tagged along with him just to get out of the house; fashion wasn’t something I really wanted to learn about — yet. My dad had a huge photo album of all of the pieces he made, and the things he wore. It’s very similar to the inspirations that inform my collection. Even before my dad was a designer, he and his friends were super-fashionable. They were wearing some next-level pieces, and making the clothing their own. As I got older and began gravitating more towards fashion, looking through his photo album lead me to pursue more research. I got a library membership at the Met last year. I’m always there, digging into contemporary African photographers. The moment I saw these [Sidibé and Sanlé] images, they reminded me so much of my dad’s album. Back in Nigeria, studio photography is so popular. People do it mostly around Christmas or Ramadan, when everyone is all dressed up in their best attire. It’s something that repeats itself in every generation in Africa.

I’ve always loved Sidibé’s pictures of people dancing at parties, too. Does music inform your approach to design?

Completely. I think it’s a very Nigerian thing. Regardless of whether you are Nigerian and born in another country, or you’ve never been to Nigeria, you still gravitate towards Nigerian music. Growing up, I listened to genres like Fuji, which is from the Yoruba, Jùjú, and Afrobeat, originated by Fela Kuti. Out of everything, I gravitated towards Fela the most.

What about his music drew you so strongly?

The energy. It’s just amazing. Fela’s songs go on for 40 minutes. Mostly instrumental, but there are unexpected moments where his voice comes in, and it’s just so powerful. He’s known for his political activism, too. There’s a song that inspired the name of the brand, called “Coffins for Head of State.” It’s about political corruption in Nigeria. The government invaded Fela’s house and threw his mother from the roof to her death. He channeled that emotion, that aggression, into such a powerful song. He talks about bringing his mother’s coffin to the doorstep of the president. Coming across Fela changed my whole perception of things. Growing up in Nigeria, I had to be socially and politically aware very early on. I knew corruption was very rampant, and there are different layers of it. Getting exposed to this so young, it was normalized in a way. I see a lot of Fela’s songs as prophecy. He predicts the future — the direction — of the country. And pretty much all his predictions have been on-point!

I can’t imagine what it must have been like moving here.

It was very eye-opening. “Brotherhood” is a balance of my culture, and my assimilation of American culture. I think design plays such a huge part in the idea of a utopian society. There’s a reason for everything in design — the way the New York City subway system is run, how water pipes work. That’s one of the biggest things I’ve learned moving to America. I ask myself: How do I design with intent? How do I make something make sense with reason and emotion?

Early on, the ideas for Head of State+ were there, but the funding wasn’t. It really is like school: the more you study, the better you’ll have an understanding, and you’re more likely to pass the class. The more research, effort, and money that went into the collections, the better the story was told. I still have small budgets, but now I know how to better apply them. In the future, I’d like to work on furniture, installations, product design. It’s like I’m writing a book, and now I’m on the third paragraph of the first chapter.

You’ve also worked in film.

Youth FX is the coolest thing ever! Films made through the program have screened, and won awards, at the L.A. Film Festival and Tribeca. It shows what happens when you give underprivileged people opportunities to express themselves without expectation. I used to download bootlegged architecture software because I was really curious in learning more about it. What if I had access to the real thing? I mean, these kids are making movies that could easily get them into NYU.

Speaking of school, did you ever consider studying fashion?

You know, I applied to FIT, Parsons, and Pratt, but I have no idea if I got in. As soon as I got my first email from [United Arrows], I never read my admissions letters. I still have them, somewhere. Someday, I’ll check!

All images courtesy of brand.