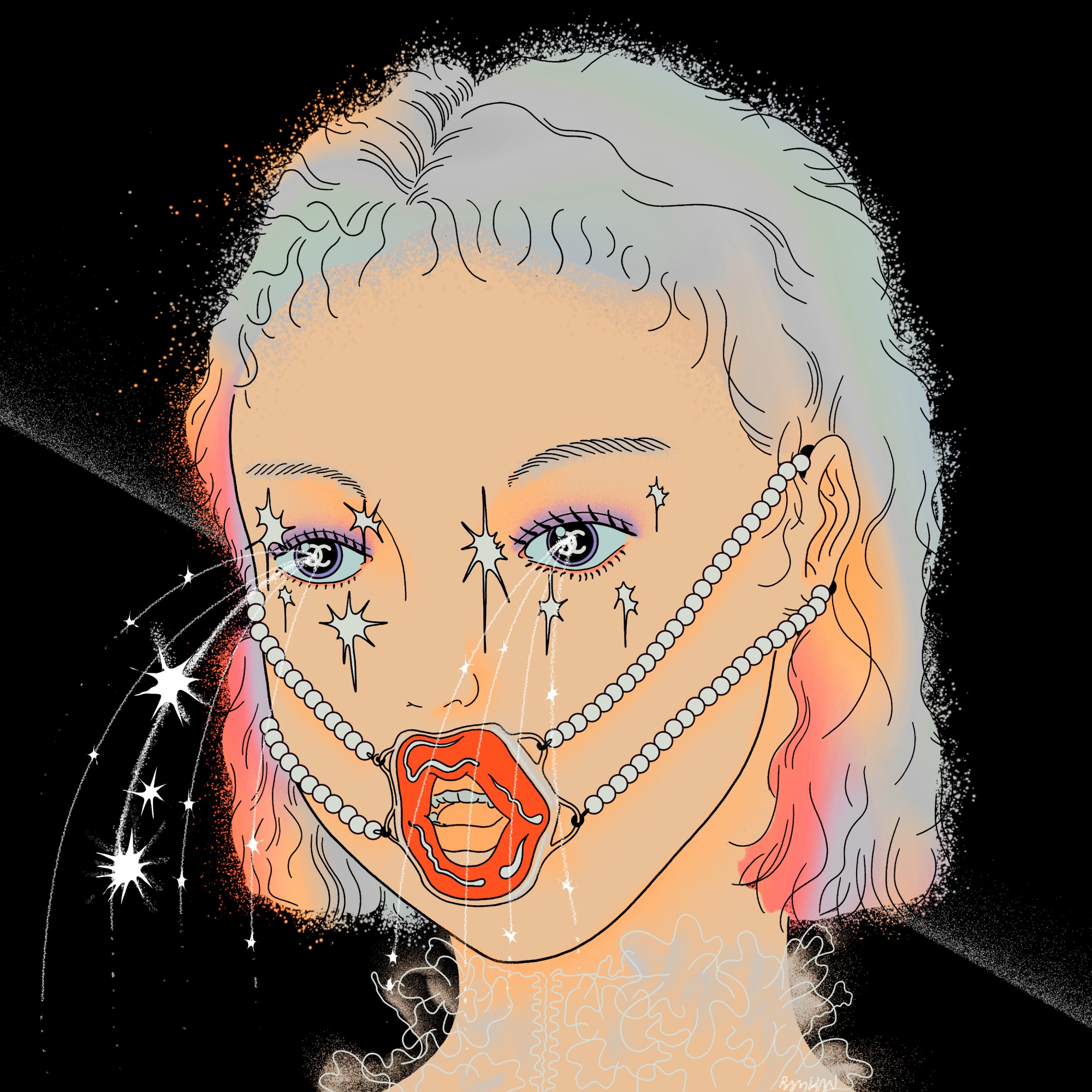

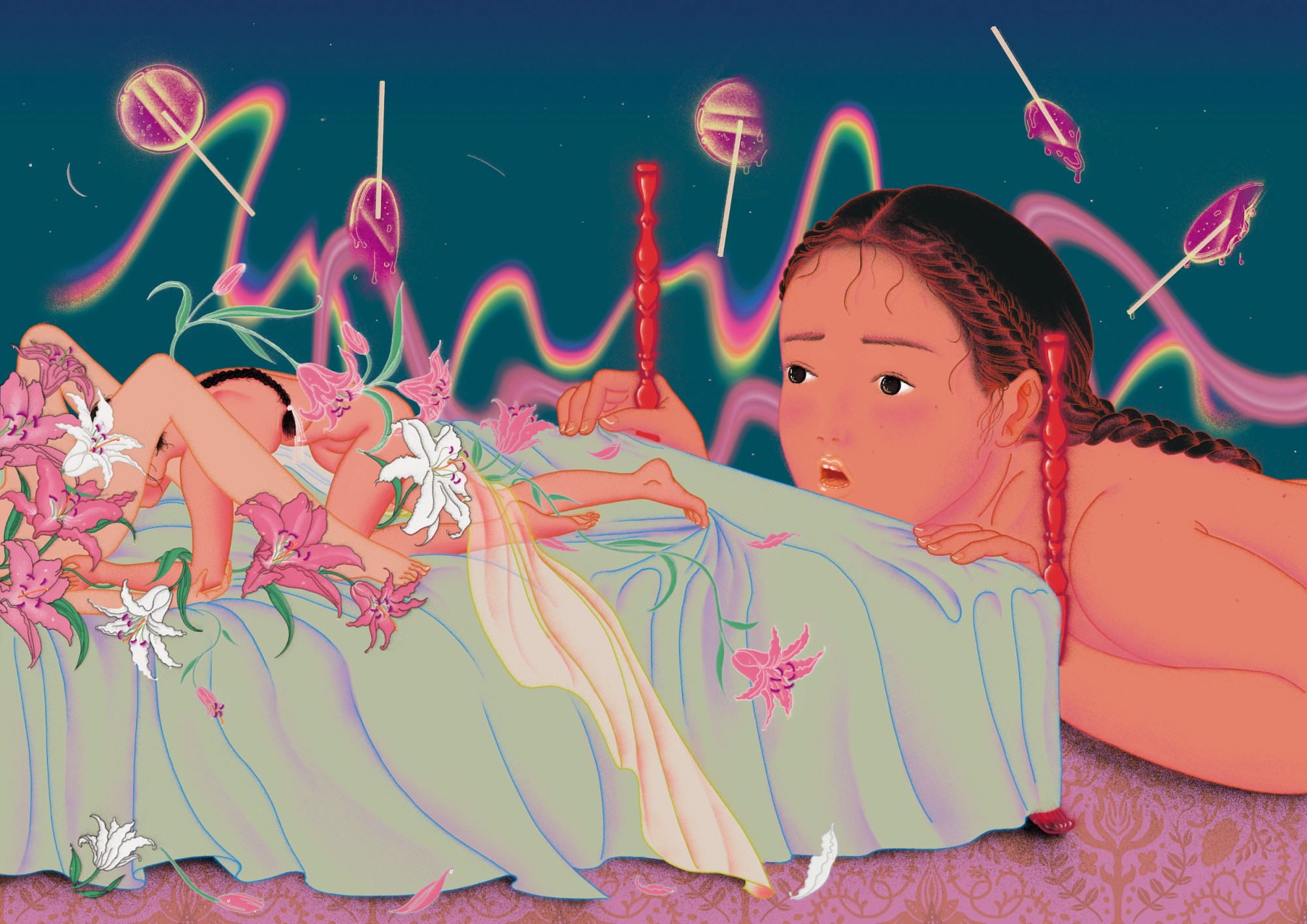

Seoul-based artist Ram Han’s digital drawings are seductive and surreal: In “Flowers,” a giant girl watches two women fool around in bed, as lilies sprout from their flesh and airbrushed rainbows and lollipops swirl in the air. The dreamlike atmosphere of her work is pulled from fragmented memories — such as the colors and textures of cartoons she watched in the 90s. But the sexuality in her work is a reflection of the male gaze; she is appropriating a man’s perspective in order to express her own experiences as a woman. “My sexual fantasies have been male-oriented since I was young because I have been exposed and deeply influenced by male-oriented media such as films, anime and TV commercials,” says the 29-year-old artist. “Even now, it’s still a part of my fantasies.” In addition to exploring her desires, her work captures complex emotions, such as nostalgia or self-doubt, which are visible in her provocative characters and lavish bedroom scenes. “My paintings are sort of like writing in a diary,” Han says in the following interview, “but instead of writing sentences that start with ‘I,’ I am exploring my emotions through art.”

How have the 1980s and 90s informed your style?

The style of my work comes from fragmented memories; from the colors and textures I saw in cartoons and commercials on TV. I was also inspired from illustration books from the 80s and 90s, mostly of Japan’s realistic airbrush style. When I was young, I was often at my aunt’s house, who was a graphic designer, and I remember leafing through all kinds of airbrush books on her shelf, and wondering how the paintings were that realistic. Maybe if someone lived in a similar time or area as me, they can see the nostalgia in my work. But even on the other side of the globe, people who have seen similar-style TV ads in the 90s can feel the nostalgia too.

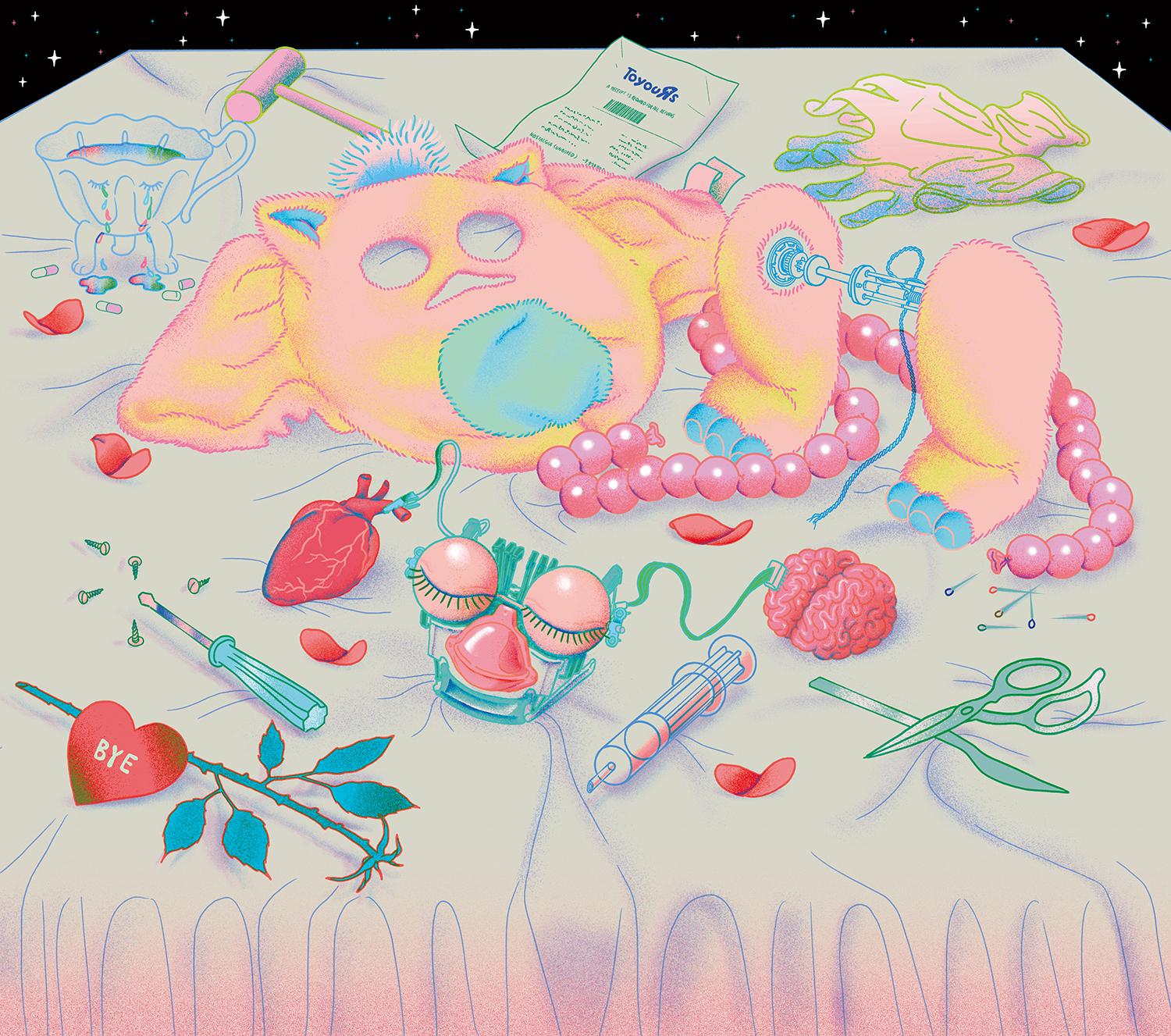

Why are women, and sometimes cats, your main subjects?

Choosing women’s bodies and cats as subjects was as natural to me as breathing. I spend most of my daily life with cats, and I am a woman — a complicated yet delicate being. My early works were closely related to emotion (most of the female figures represented one of my feelings), but now, with a more feminist perspective, I want to portray women’s bodies slightly differently, and show how women feel on a deeper level.

Speaking of feminism, when did it first start to take hold in Korea? Was there a specific event that happened that started the movement?

At least in the field of art, it was the result of a specific case, and the impact slowly spread to society. About two years ago, it started with a movement of sexual assault accusations in universities. I was one of the accusers, even though I had already graduated. But even before the accusations, all the girls knew which professors and boys committed sexual abuse. As a result, some of the faculty members were disciplined or suspended, and some students were expelled. As it started to become publicized, similar kinds of issues were pouring out, and both female artists and art students began to realize that their silence could have caused secondary victims.Now, there have been changes in the attitudes towards discrimination and institutional misogyny, and women as a group often raise their voice towards these discriminations.

What are the main issues women are still fighting for in Korea? Is it equal rights, equal pay or something else?

All of the above are being actively addressed in Korea. But recently, digital sex crimes became a big issue. In Korea, many women committed suicide or suffer permanent psychological damage due to illegal footage taken of them in hotels, public restrooms, schools or subway stations. Korean women are concerned about hidden cameras; this is a common fear that most Korean women have had for quite some time. And although it is changing rapidly, Korea is still a very conservative country. Until a generation ago, mothers had abortions on girl fetuses, as they only wanted sons. And when it comes to abortion, which is still illegal, only the hospital and the woman is punished. The men are never punished. Similarly, men’s perception of women’s activism is extremely negative, and a pretty large group of Korean men believe that feminism is just about hating men.

How do you think men’s perceptions shaped your art? Sometimes it seems as if you draw from the male gaze.

The way I approach images is directly influenced through the media. Imagine the media is a mirror — what happens when I (a woman) see my reflection and draw my face? I will draw it through the lens of the male-oriented media. I think my work can be explained, in some part, that way.