When I visit Stephen Ostrowski’s Chinatown studio, I sit on a couch by the window. Bright green and slightly oblong, the sofa looks as though it was plucked from one of Ostrowski’s active and colorful artworks. Some of his pieces are exercises in abstract mark-making. Others are representational, and tend to feature crosses, flames, or flowers — iconography the artist was exposed to growing up in an evangelical missionary community in Thailand.

Ostrowski eats breakfast and tacks up drawings while telling me about his time in Southeast Asia. His parents are originally from the midwest. His dad was born in Wisconsin, his mom in Iowa. The family moved to Bangkok when he was in elementary school. “People like me are called third-culture kids,” he explains. “You have a home country, dirt you’re technically from. But you grow up in a completely different culture. So your existence becomes this synthesis of two things that creates this third thing. It’s sort of relative to both, but also isn’t either of them. It makes ‘home’ more a bodily concept for me. My roots are very abeyant.”

As a teenager, Ostrowski was able to explore Bangkok with relative freedom. His parents weren’t as overbearing or rigid as others in the evangelical community. (Besides, he was their fourth child — the rules his sisters lived by had loosened over the years). He rode motorcycles around the city, skateboarded, copped cheap weed. “The first time I got drunk was underneath a huge trans cabaret,” he says.

Despite living in a culture known for its relaxed, fluid attitudes towards gender and sexuality, Ostrowski’s parents sent him to conversion therapy. This inhumane, ineffective practice uses methods of psychological and physical torture to “cure” queer people of their “homosexual disorder.” At 16-years-old, Ostrowski was encouraged to violently alienate himself from his sexuality, “a fundamental component of our being,” he says.

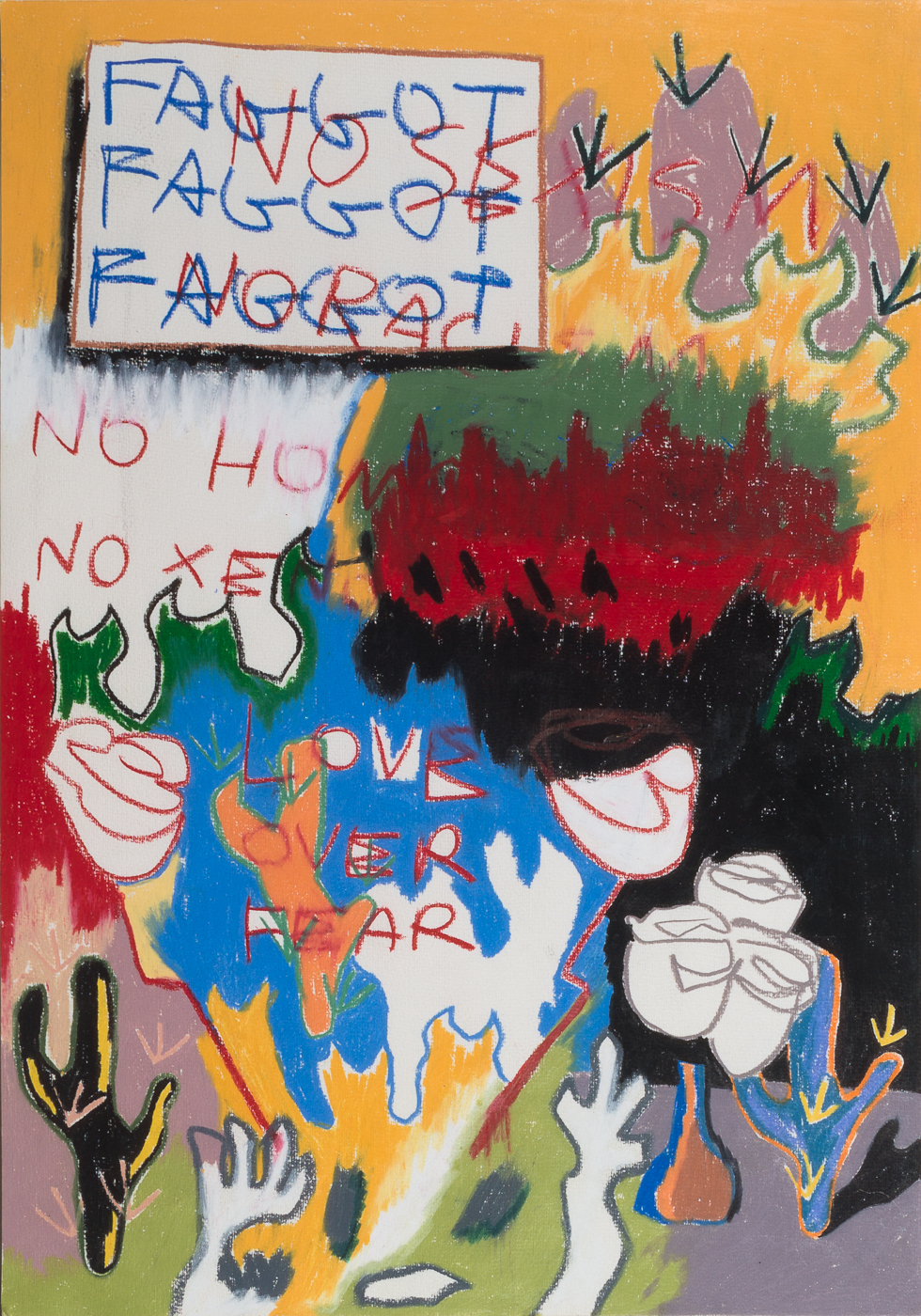

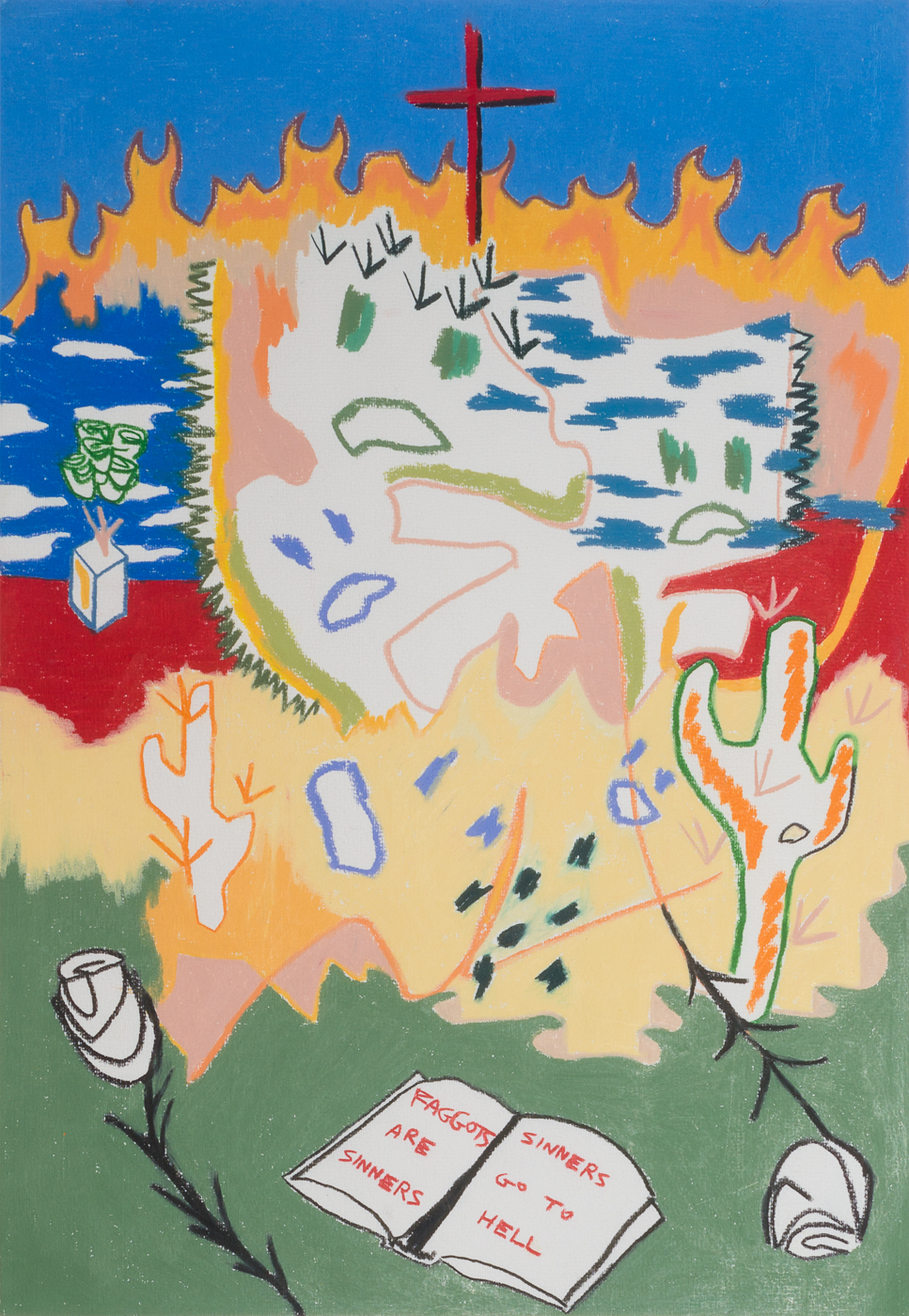

Ostrowski began making expressive artworks four years ago as a way of processing his experiences, and his survival. Earlier this month, he opened Side effects include: hope, nausea — an arresting exhibition of interdisciplinary works curated by Vivian Chui — at the Spring/Break Art Show.

“The public nature of my conversation about conversion therapy was reactionary,” Ostrowski explains. “I’ve only seen one documentary about it. Then, pre-election, all that shit came out about Mike Pence funding Christian organizations that perform conversion therapy with Indiana tax dollars. I thought, ‘No fucking way am I not talking about this.’ It’s the important, vulnerable, real, grit life experience that if you don’t talk about it, it crushes you. I told myself that it wasn’t going to crush me.”

What was it like growing up in Thailand?

I think what is the most difficult about my history, and the history of others like me, is that throughout your childhood and adolescence, you are told you’re “from” somewhere else. I grew identifying as someone from the U.S. because that was where I was born, that’s where my the paperwork says I’m “from.” But culture is learned, so when you’re seven years old and living somewhere, you are that culture. It was more culturally shocking moving back to the United States at 18 than it was living in Thailand at all. I felt like more a foreigner moving back than I ever did growing up in there. Bangkok is wild though, and I was allowed to run amok. We all rode around on little 50cc motorcycles, I skated every day.

Is there a skate scene in Bangkok?

Definitely. I started skating when I was young. I have three sisters — one is five years older than me; two are twins, and they’re nine years older than me. They had friends who skated in high school. One of my sisters had a board, and she kind of tricked me into buying it. Once I learned how to skate, it was all I wanted to do, all I cared about.

It sounds like you were able to experience so much of the city.

The insane public transportation makes every crevice of Bangkok accessible, so we’d go wherever we wanted. The kids that I was the closest to — who I hung out and partied with — were all from the church I went to. In Thailand, the drinking age is 18, but alcohol is more or less available at any age. Kids would get fucked up at the park I skated at, Queens Park, which was sort of like Tompkins Park [in NYC]. The first time I got drunk was underneath a huge trans cabaret down the street from it. My last memory of that night is being surrounded by beautiful Thai trans women in extravagant rainbow feather dresses pinching my cheeks, telling me how cute I was, laughing at how drunk I was. We would go downtown to these mega malls that are like, seven stories tall or take trains to markets all around the city. I’d buy defective Vans that came from the factories out there. We used to go to this one guy’s shop every weekend who sold pirated albums. He had such an eclectic selection. He introduced me to so many things. He had Minor Threat to Madonna. Whole discographies of New Order, Placebo, Aphex Twin. I bought my first Daft Punk album from him. My first Brian Eno album, too. I had a Lou Reed shirt he made that said “Rock n Roll Animal” on the back and had that album cover on the front. Bootleg shit that doesn’t exist anywhere else.

Tell me about your experiences with church and conversion therapy.

I feel there is a toxicity to fundamentalist attitudes generally, in any place. Institutionalized Christian religion seems to prey on the basic human instincts of desire and fear. The desire to belong to something, to be visible, to feel like you exist. The fear of loneliness, of dying, of the unknown. Instead of coming to terms with the temporary nature of existence, people cling to ideology. The only thing they feel they can do is convince themselves that they know what’s going to happen after death, but the truth is, no one knows. And anyone that is claiming they do with certainty is doing so falsely. It’s all so conditional — submit to an ideology, this box of what’s allowed. But the moment we contain and label something, we immediately limit its possibilities. Conversion therapy is all of that compounded. ‘God loves you, but not like this. God could love you, but he doesn’t, because you’re gay.’ As a minor, they penetrate your psyche and plant a seed that your sexuality — a fundamental component to your genetics and your existence — makes you flawed and fundamentally unlovable. Being non-heteronormative is an abomination, it means you’re hell-bound. The only way out is to extricate it, like it’s a demon. Its purpose is to make sure someone like me doesn’t positively integrate their sexuality, the way they intuitively show love, into their life.

That’s barbaric.

It destroys people. What is life without love? I call it intellectual rape. My parents are not malicious people. They were trying to navigate murky waters as best as they could within a community that was very hostile towards a person like me. After I went, I said anything to not go back. ‘I’m good, I talked it out, I don’t need to go again.’ I was scared, but I didn’t let them know that. People get electroshock therapy performed on them. They’re shown erotic images of men while hot coils are put on their hands. It becomes torture. Adults, fuck yourselves up however you want. That’s on you. But the fact that conversion therapy happens predominantly with minors is unacceptable. There are only three states where it’s illegal to perform conversion therapy on minors. As of January, bills to ban it are pending in the legislatures of 18 states. But that’s pending, and literally two months ago. It’s a miracle that people make it out and they’re okay. The whole point is to convince yourself that you’re not an acceptable person. And the danger of it, especially with minors, is that you don’t know any differently. They tell kids, ‘If you don’t change, you will burn in hell forever.’ That stuck with me. I would always paint hell, and draw flames on shit. I use that sort of iconography in my pieces now, because that’s how I rendered them as a child.

What motivated you to make artwork about conversion therapy?

When I was maybe 25, I had already come out, but I something was so wrong in how I was feeling. I had dislocated my elbow, so I couldn’t paint, couldn’t skate, couldn’t work. I couldn’t do anything but sit and think. I found myself wondering why I hated myself so much. I realized that I had really repressed what that experience was, and what it did to me. It was like I was looking around a dark room with a flashlight. ‘I don’t know what I’m looking for, but where the fuck is it?’ Then I pointed at it. ‘There it is. That’s it. It’s so tiny, dense, heavy. This is why I feel this way.’ That’s when I started repairing, and when I started painting about it. Shame and acceptance were already being discussed heavily in my practice but after that, I didn’t want to talk about anything else. There was nothing else for me to talk about.

How did your practice develop?

Before I moved here, a friend and I had renovated a building in Detroit, where we lived. I was starting to outwardly process things in a physical sense, so I began painting on the walls. Another friend of mine, a graffiti writer, needed money to buy a bus ticket to Chicago. He’d stolen a huge amount of oil paints, and told me I could take whatever I wanted if I gave him $20 for the ticket. So I just picked the colors I liked, and went from there. Because skating is such a big part of my life, injuries have always lead me to other things that I needed to be doing creatively. I injured my knee the day before I moved to New York, and painting became an important way for me to process things. It has a similar quality of mindless physicality that skating does. Kind of like a meditation. There’s an immediacy to the gratification of what’s happening, but also, there’s continuous movement which helps me to be present.

At first, making art just felt like a good expressive outlet. But once I figured out how to put my feelings onto something blank, it took on this ethereal power. Now anything that I want to communicate, there’s a way for me to manifest it, and put it into the physical world. Writing is an important part of my practice, too. Since I use a lot of recurring images to represent things — to develop a visual language — the writing and iconography build into each other. They’re constantly in conversation for me.

How did the Spring/Break show come about?

I had pieces at a friend’s apartment and a curator, Vivian Chui, was doing a studio visit with him. She liked my pieces, and emailed him about them later. He put us in contact, and she came over for a visit. I didn’t know much about Spring/ Break when she told me she wanted to do it. The theme of this year’s theme was “A Stranger Comes to Town.” After reading the prompt, I started thinking about what it means to be a stranger versus what it means to belong. The whole idea of conversion therapy is to make a person a stranger in their body. Make them a stranger to who they are. Make them estranged to a fundamental component of their existence. Last year, I made a zine of poems and writings about conversion therapy — writings I’d originally done in 2013 — under the same title, Side effects include hope, nausea. So I knew what I wanted to communicate with the show, and I’d already made most of the works.

As a viewer, the fair experience can sometimes be overwhelming. What was it like as an artist?

Especially considering the nature of the show for me, very overwhelming. I had to do a lot of emotional preparation. Luckily, I have the most amazing support system in the world. At least one or two friends came every day. I was kind of scared, but everyone I love just showed the fuck up for me. Just to hold my hand.

A few days after our conversation, Ostrowski emailed me this afterthought:

All things we experience here — pleasure and pain, loss and gain — can feel mundane and yet be so profound. This world is in opposition to people like us, so I share my truth in hope. Hope that people will change, that we can change each other for the better. We are here for such a brief moment in time, to teach and learn and grow and show what we’ve been through so that it may help those who are drowning like we once were, like I once was. After your visit, I reread journals from that time, describing this crushing shame. An oppressive weight on my soul. Reading it now, it feels almost unfamiliar. To have found beauty in such devastation has been liberating. I feel the power of honesty, of openness, of truth. I realize what was once my shame has become my greatest treasure.