Do you sometimes feel like you’re falling down a rabbit hole when scrolling through your feed? Well, it’s hardly surprising. Over 100 million photos are uploaded on Instagram every single day. It can be overwhelming, but Benjamin Wolbergs — editor of New Queer Photography, the new book empowering queer voices to tell their personal stories — sees it as a purely positive thing. “Today, every artist can present their work on social media and be discovered by a worldwide audience,” he says. “This leads to great diversity regarding many different aesthetics, visual worlds and topics we see today in the field of queer photography.”

From up-and-coming artists like those featured in this piece, to more established filmmakers and photographers like Matt Lambert and Laurence Philomene, New Queer Photography unites over 50 different contemporary perspectives on the lives of the LGBT+ community from all over the world. “It was important for me to present as many photographers and queer imaginary worlds as possible, to trust my intuitions more than overly dogmatic approaches,” Benjamin says about the research process, which took him over four years. Here, we get to know four up-and-coming artists involved.

Lia Clay Miller

Tell us the story behind the photos published in New Queer Photography.

These photos were a combination of personal portraits I took of friends, as well as a few images from editorial stories that I worked on. The image of the person sitting near a window with angel wings was my dear friend Nico, who sadly passed away last year. The idea to put angel wings on him wasn’t something I really thought about much until after.

What makes a photo a good photo for you?

There are a lot of things that make a photo good to me, personally. Not a lot of it has to do with technicality, but I think a remarkable photograph can always be traced back to the photographer in some way. It’s known, rather unplaceable in the sea of media we view on a daily basis.

You want the representation to be less about yourself and more about who’s in your work. Who are the people in front of your lens?

My feelings about representation are more focused towards the level in which I’m working, and other queer and trans creatives are working. Often, we’re given subjects and projects that kind of shut us out of the rest of the industry because we are only taken to be representations of our own marginalisation. It took so long for me to be in the same place and go beyond working predominantly based on representation. The people in front of my lens always change, but my favourite moments are always with people I can find some sort of similar connection with, who understand what I want to portray, and who can have a meaningful dialogue with me to help get to that place. It just happens that the majority of my personal portraiture is with other trans individuals because I feel like communication in that space is something we just understand about each other.

What would you like to say to someone reading this?

Don’t let the industry define you, define yourself in the industry. It’s a small shift in perspective, but it matters the most, I think.

Hao Nguyen

Tell us the story behind the photos published in New Queer Photography.

The images are mostly personal work I’ve captured of my close friends and the people I’ve met through social media.

What do you hope people take away from your work? And what do you personally take away from it?

I hope people can see how everyone’s journey is different, yet recognisable. Viewing my images is an ongoing reminder to keep working towards becoming a healing person instead of a hurt person. I try to see the qualities I admire in each individual I connect with, hoping to see more of those in me.

You have a strong interest in identity and queer expression. What inspires you to create your images?

The demand to see changes in myself inspired me to create work. I’ve only been introduced to a wider spectrum of the LGBT+ community after experiencing the heart of NYC two years ago. Coming from the suburbs outside of Toronto, it required a lot of adapting to unfamiliarity, as well as realisations about the importance of togetherness, and the ability to express one’s self in the truest form.

What does being queer mean to you?

Being queer means to continuously break away from living in normalcy.

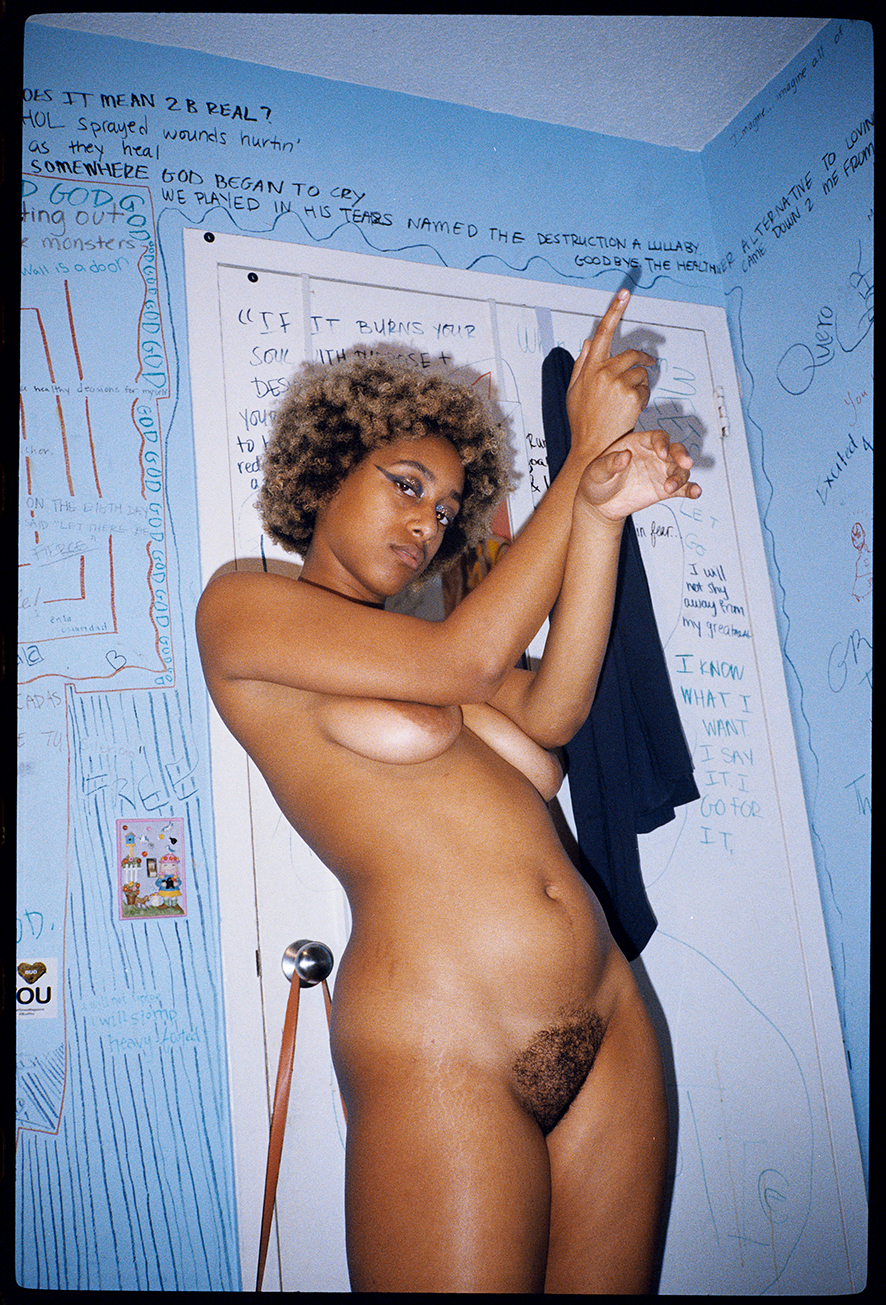

Maria Clara Macrì

Tell us the story behind the photo series published in New Queer Photography.

It’s part of my project In Her Rooms that was shot during my travels across the US and Europe. I never travelled with a precise plan, the only one was to find my subjects. Through them, I portrayed a woman who creates her own culture, world and way of living outside the lines society wants them to stay – constantly in the process of discovering herself.

You’re known for experimenting with empathy, intimacy and female representation. How much are empathy and your work intertwined?

I share empathy with people, especially strangers. It’s part of my way of being, with and without the camera. I think it’s because I’m in a constant process of exploring my emotions without any boundaries. It gives me the privilege to be honest and without any filter when I’m with others. As a reflection, my opposite immediately feels accepted, welcome and understood. Empathy is the energy in which we find each other. Without empathy, In Her Rooms would never exist.

Where do you find the women and who are they?

I contacted some of my first subjects on Instagram, especially when I was in New York, and others wrote to me on Instagram as they really wanted to be part of it. I still found most of them in the streets, and some of them were the connection to others. They are all girls with strong personalities. Creatives who are free and wild. Moon daughters who are brave enough to be themselves, also in their fragilities. Now they are part of my life even if they are far away — my friends and sisters.

Most of them are naked or barely covered in clothes. What does intimacy mean to you?

I don’t connect intimacy with being naked. Nudity is the authentic form of ourselves, intimacy is a world, a feeling, a place. Intimate is our dialogues before and during the shooting, it’s the place we are in both physically and spiritually. Most of the time, intimacy is the direct consequence of empathy. I’m probably more naked than my subjects when I share their photos because I’m talking about my vision and sense of sensuality, my intimate gaze on women, my fantasy, my experiences and my truth.

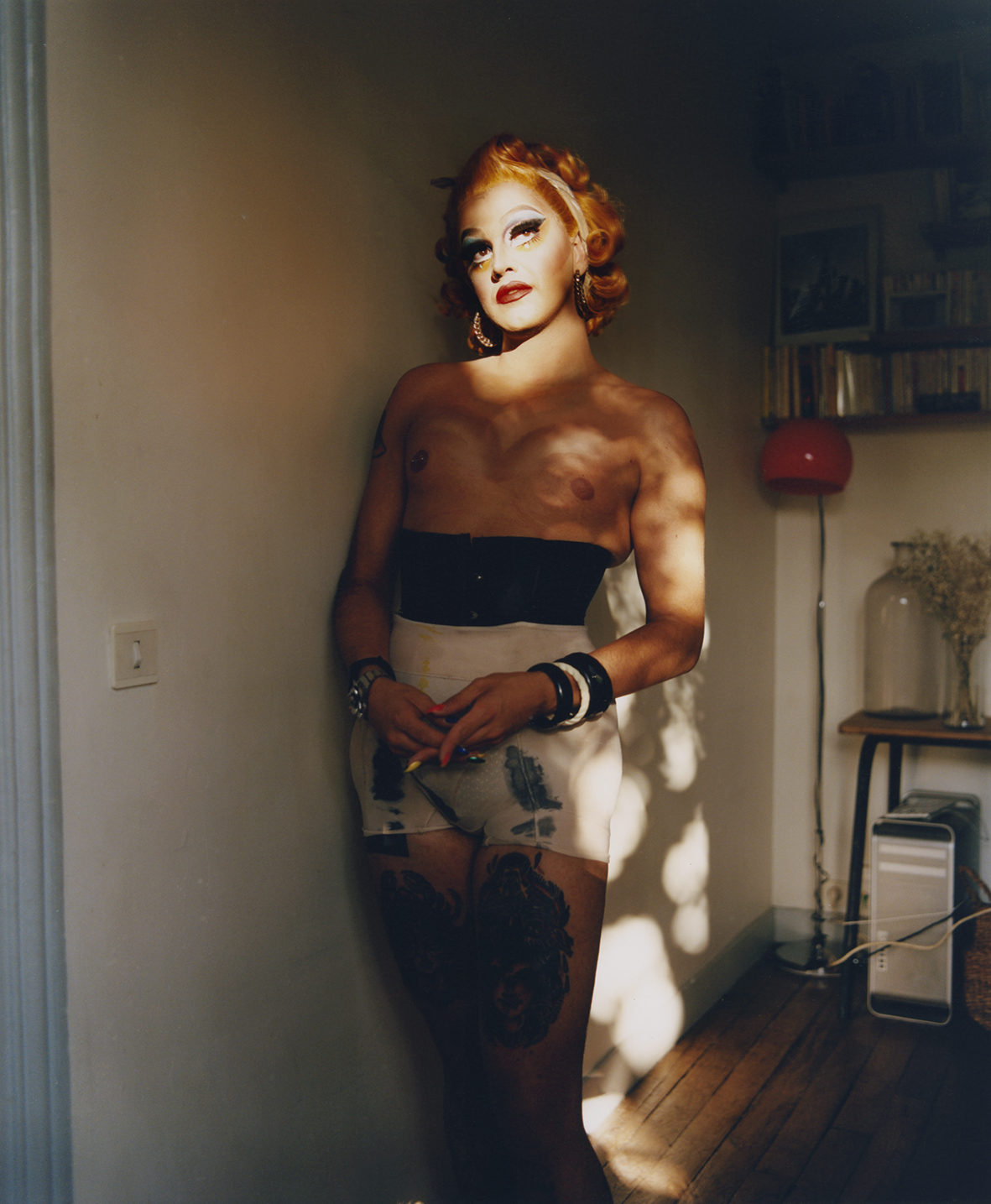

Spyros Rennt

Tell us the story behind the photos published in New Queer Photography.

They are all images taken in different queer events between 2017 and 2019. The locations vary, some were shot in Berlin others in Paris and Athens. Interestingly enough, all but one were taken in clubs and at parties such as Boar in Berlin or Menergy in Paris.

You’re at home in Berlin’s nightlife scene. How has the pandemic impacted your life and work after all clubs shut down?

My work is mostly about documenting my life and experiences. The clubs may have closed, but there’s still a life to be lived outside of them. The fact that the city had one of the mildest lockdowns and a low number of cases overall meant that the social interactions were more low key and intimate (and a bit underground). I have been creating some of my most interesting work after May of this year, in and out of people’s flats. Also making a lot of new friends and rediscovering the city.

What have you learnt about yourself and your work in the last six months?

I have discovered that taking a break, slowing down, studying some references and looking at past work can lead to a new flow of creativity and inspiration.

What makes you hopeful for the future, especially in regards to the LGBT+ community?

The fact that we are creative, resilient, resourceful and have each other’s backs.

You can order ‘New Queer Photography’ published by Verlag Kettler here.

Credits

All images courtesy New Queer Photography