The prevailing images from the AIDs epidemic are grim; scenes of concave stomachs, snaking IVs, and restrictive wheelchairs permeate our public conscious. They capture the dark realities of the plague — when doctors were still scrambling to understand the virus and presidents refused to even utter its name — but they don’t capture the lives shattered by it. We only see twig-thin victims walking towards a death sentence, not people.

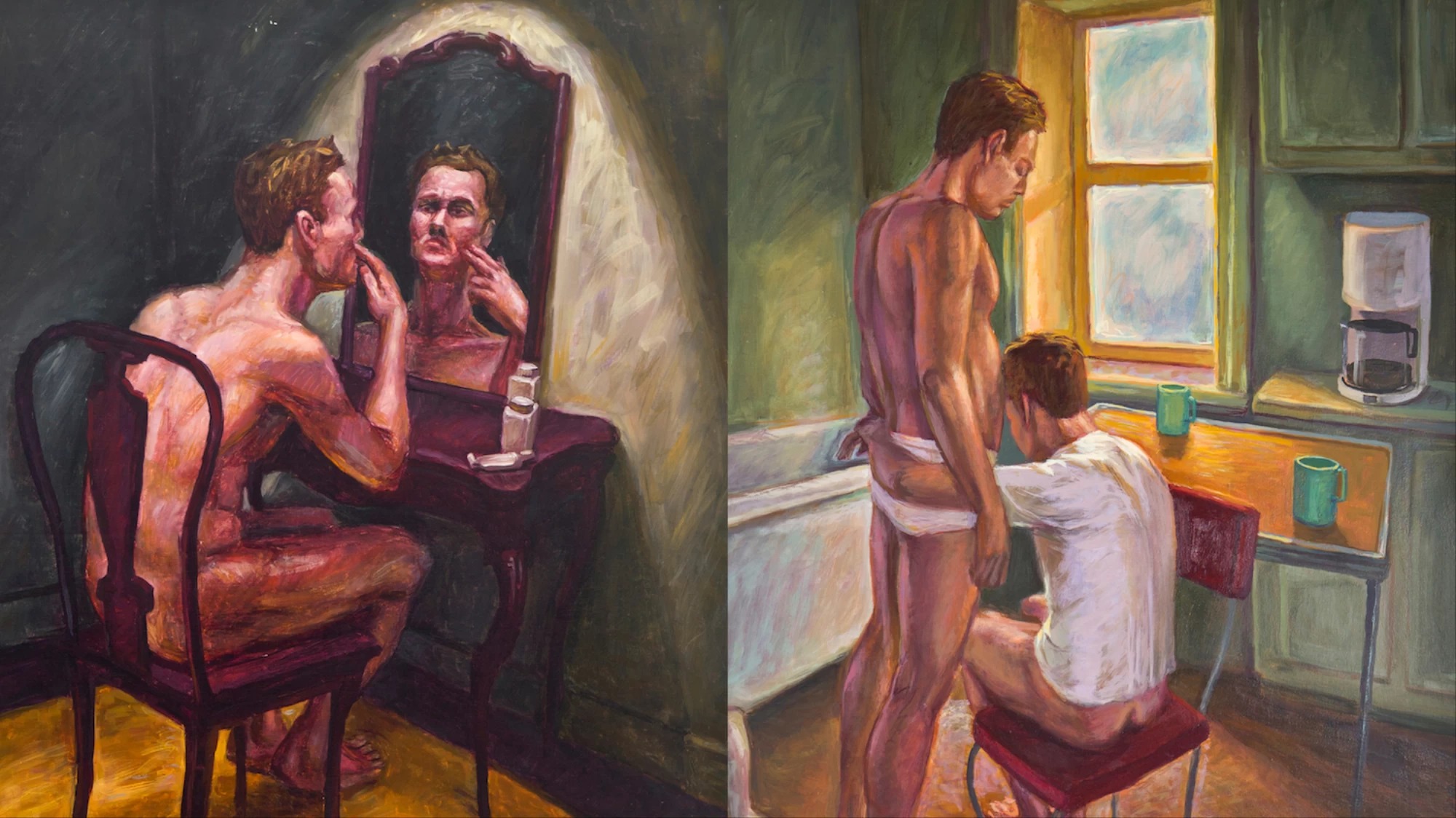

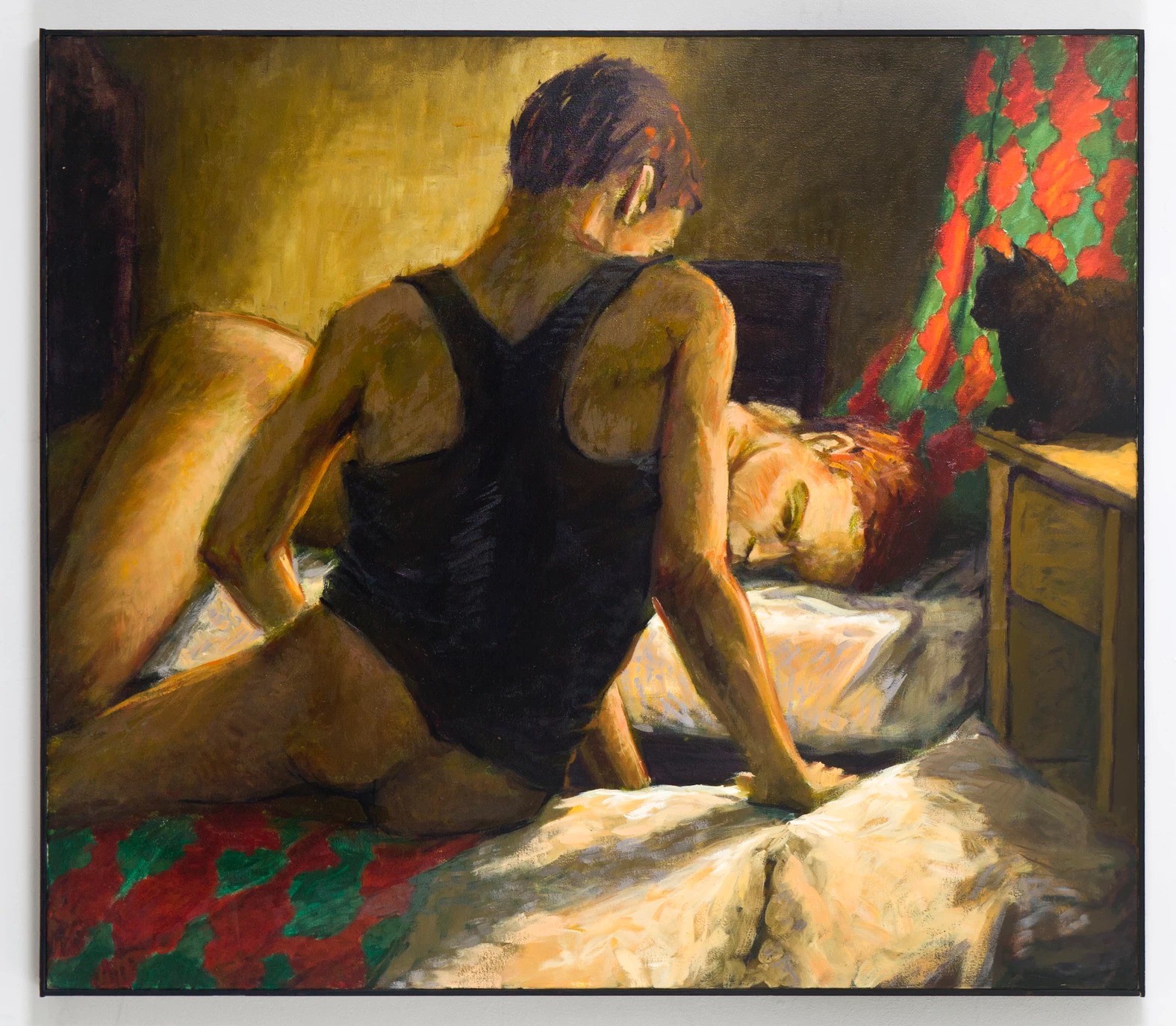

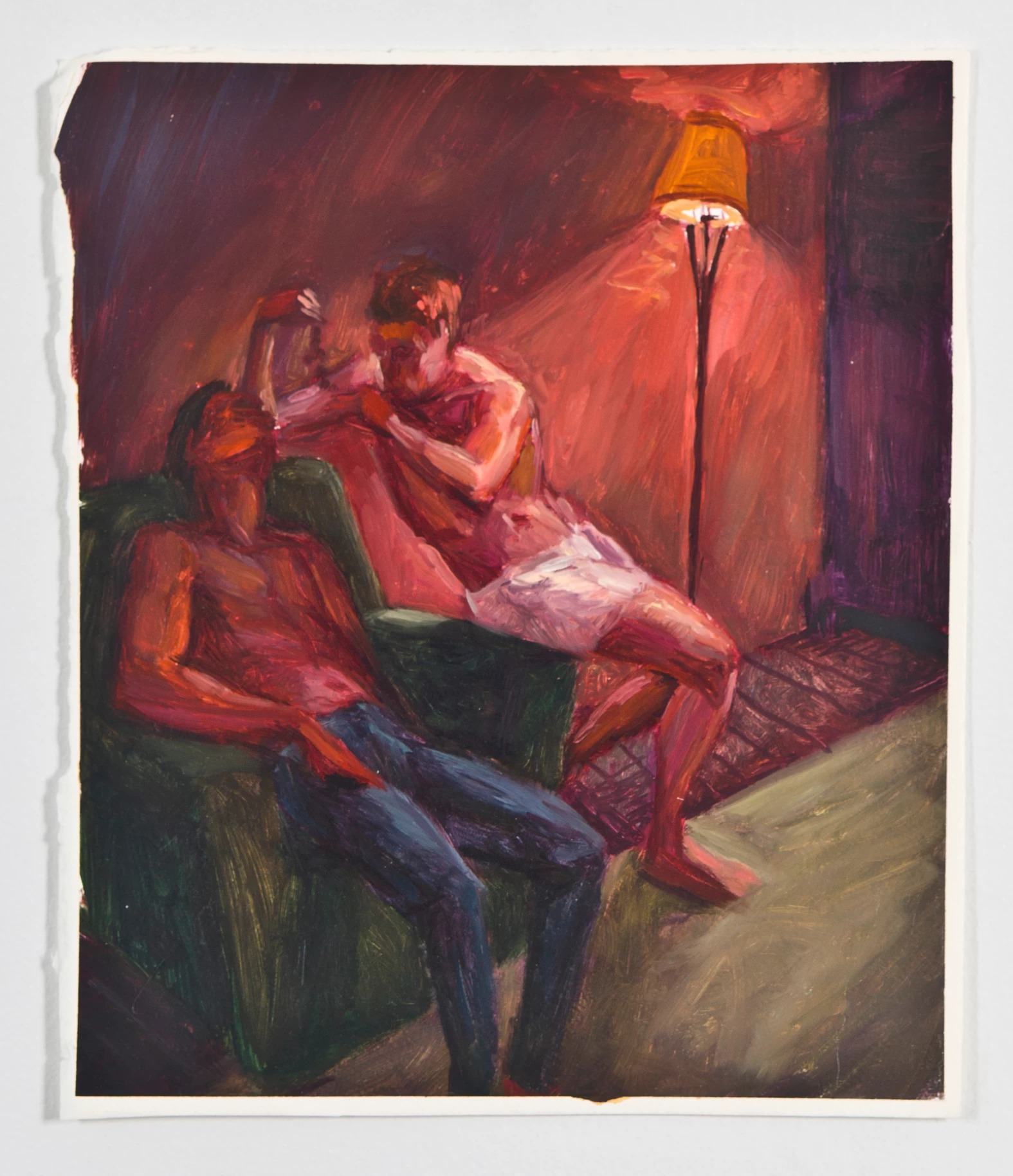

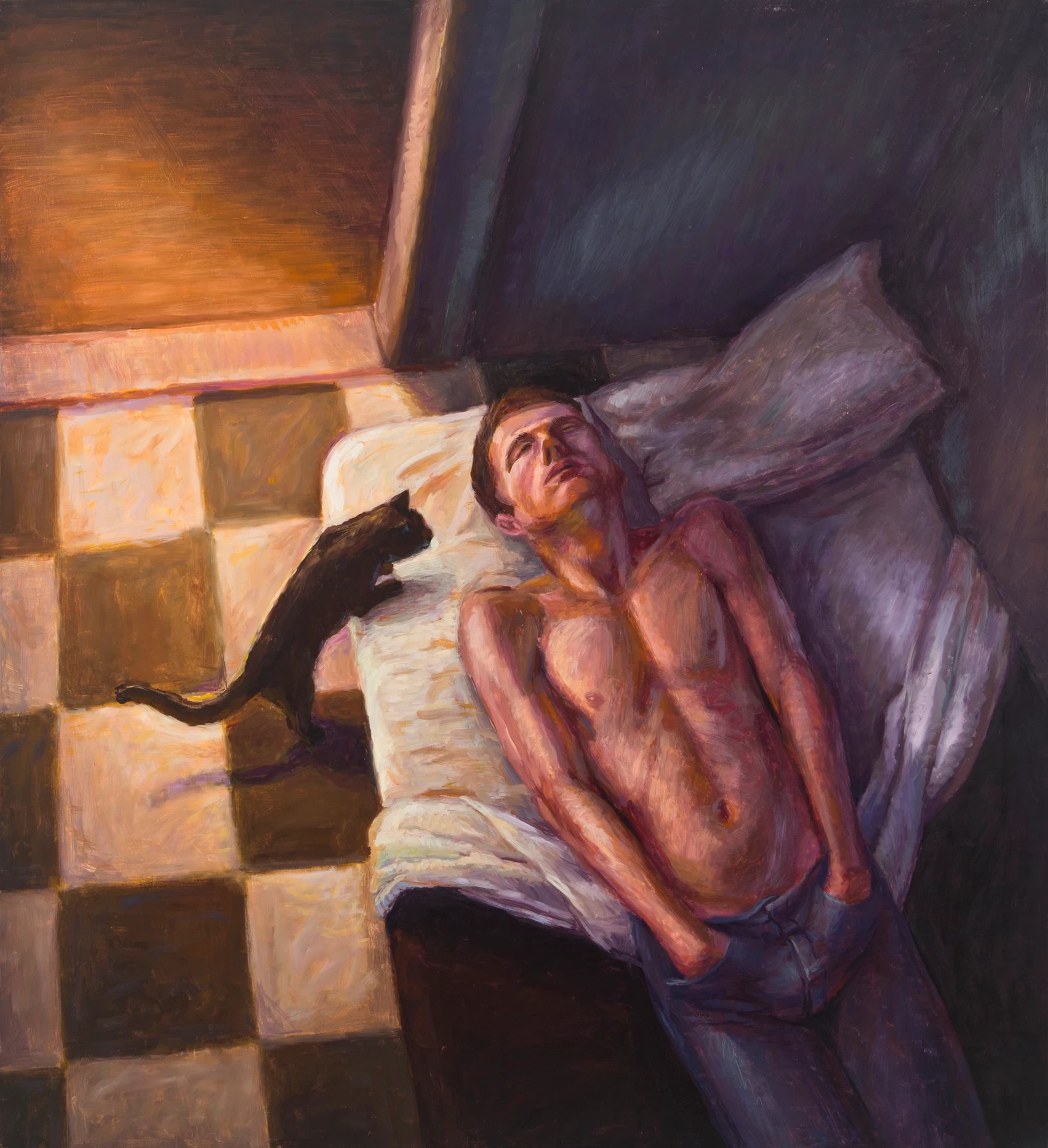

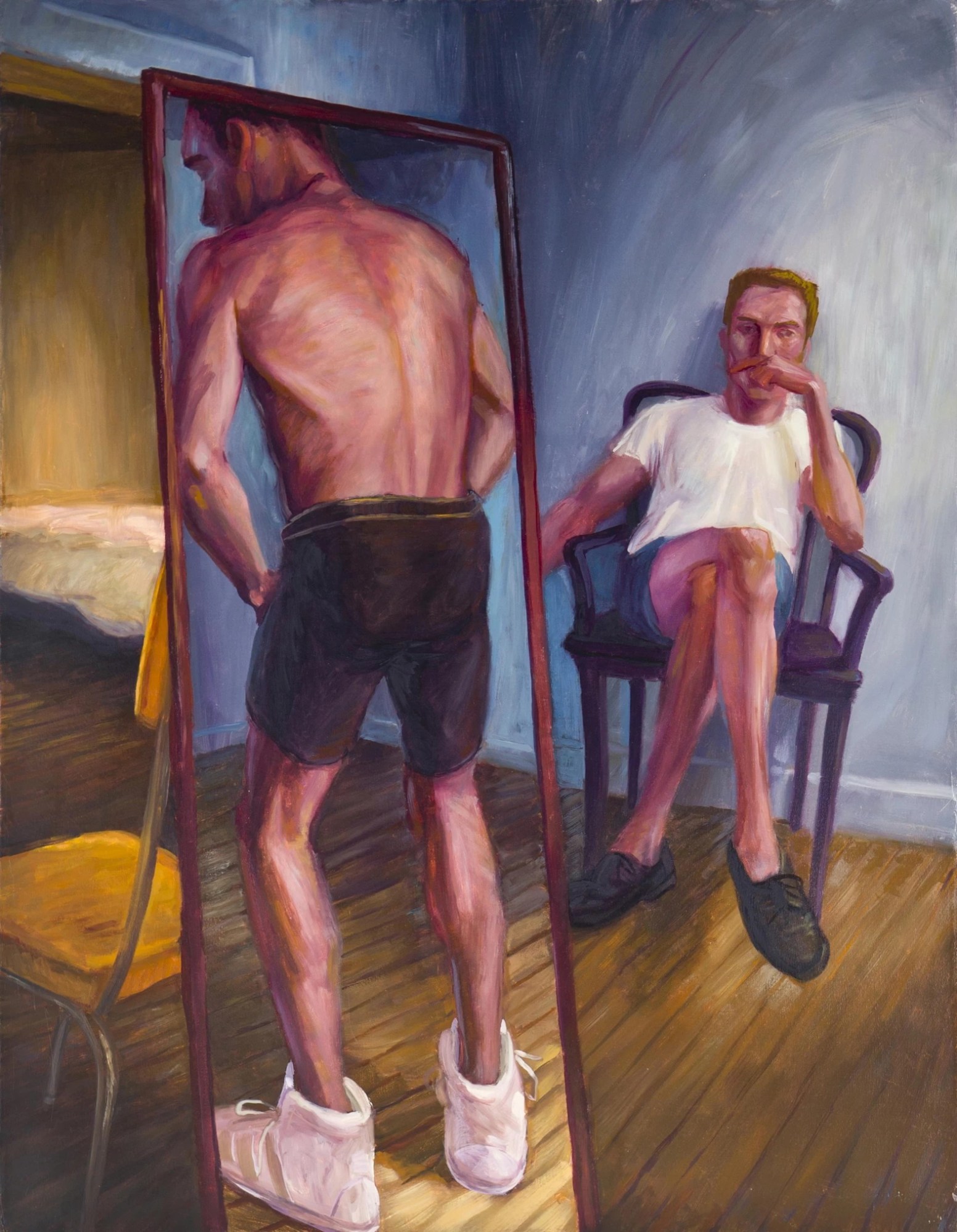

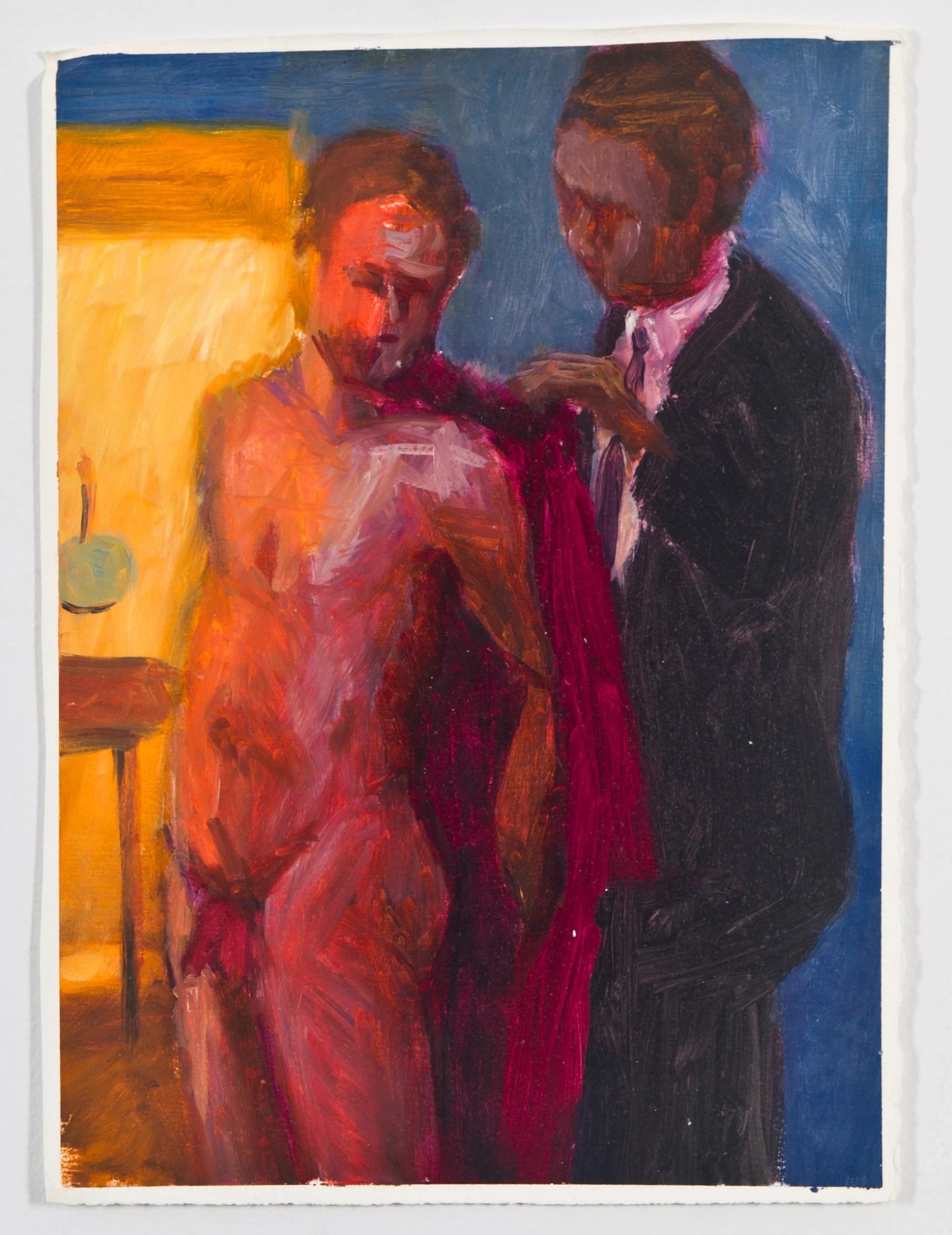

The late Hugh Steers painted queer men living with HIV/AIDs during the 80s and 90s through a humanist prism. In his hushed oil paintings, suffering intermingles with passion. A man wearing an adult diaper holds his partner near and dear. A patient makes room on his deathbed so he can cuddle with his lover. The scenes all take place in small city apartments, the domestic settings subtly touching on how HIV and queerness, both laden with stigma during Steers’s lifetime, were forced into private spaces. For example, in the 80s, numerous doctors flat-out refused to treat people with HIV/AIDs. (“I’ve got to think about myself; I’ve got to think about my family,” a Milwaukee doctor once told the New York Times.)

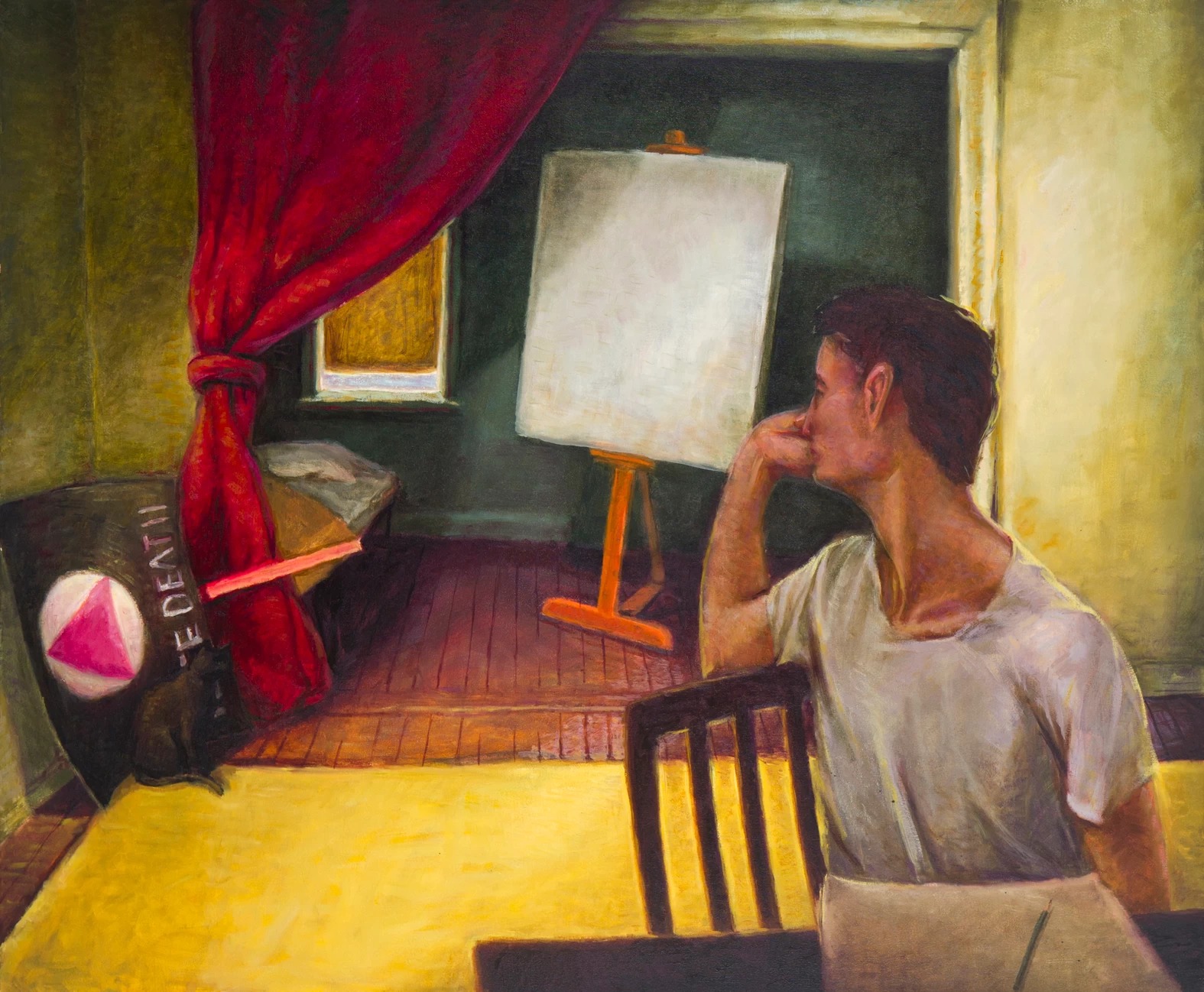

Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe created works centered on HIV/AIDs that still hang in major museums across the nation (and sometimes get plastered on Coach bags and Raf Simons button-downs). Hugh Steers, however, is far from being a household name. This might be because his work existed out of the reigning landscape of 90s art. He opted for figurative art — scenes planted squarely in the real world — rather than the popular abstractionism of artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Haring. Actually, Steers fits more neatly into our contemporary landscape. The radically soft elegance of his portraits could easily exist alongside paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Toyin Ojih Odulta.

A selection of Steers’s work is currently on display at Chelsea’s Alexander Gray Associates. The Nulities of Life is the third exhibition the gallery has staged focussing on the artist’s work. Walking through the exhibition, it is impossible not to imagine the kind of artist Steers would be today if his life was not tragically cut short at the age of 32, by the very disease he made the subject of his work. Much like queer relationships today, it is hard to discern the boundaries of what these male subjects mean to each other. Are they friends? Boyfriends? Husbands? It doesn’t really matter. What is clear is that, in a world filled with homophobic vitriol, they have no one to rely on but each other. This kind of queer solidarity has been largely lost in a era where you can pop PrEP in the morning and endlessly scroll through potential hookups.

A lone video of Hugh Steers discussing his work with an audience exists on YouTube. He is frail and bald and it feels like just talking is exhausting for the artist. Near the end of the clip, he shares why a painting of a man in a bathtub, dying in his mother’s arms, touches him so much — the work harkening Virgin Mary and Jesus in paintings, works depicting the scene commonly being called pietàs. “Michelangelo’s pietà, or any pietà, they’re not profoundly moving because it’s Mary and Jesus,” he says. “It’s because here is a mother whose son has been crucified hideously. That’s why they’re important.”

Steers’s words here feels like a retroactive message. A reminder to not let the sheer trauma and lost embedded the history of the HIV/AIDs epidemic get forgotten amidst the rainbow bracelets that get handed out by banks and brands at Pride. Queerness may be available for purchase in stores today, but, as Hugh Steers paintings poignantly remind us, not too long ago, queer men had no other choice but to die in each other’s arms.

This article originally appeared on i-D US.