Having your identity casually put under the microscope is a common source of anxiety for people who are visibly “other.” For those with faces and voices that don’t fit the prescribed “Australian identity,” it only takes a passing comment from a stranger, friend, or even a lover to suddenly feel displaced. Migrating to Australia from Malaysia in his teens, photographer Bryan Tang‘s experience echoes migrant stories of past and present.

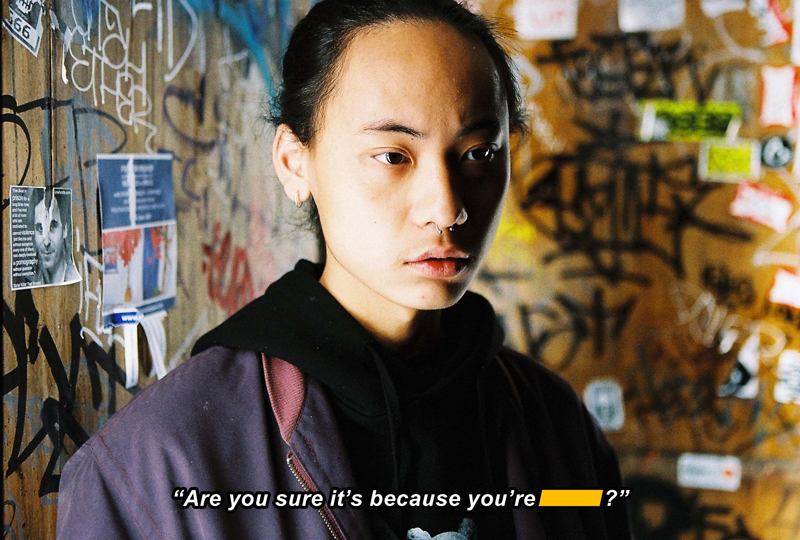

Recently, Bryan was invited to create a set of photos around the theme “Asia and Australia.” As a young fashion photographer, his body of work had mostly steered clear of politics, but after he was given the explicit go-ahead and chance to present with a group of other Asian photographers, he decided to create a series that would confront racism head on. In Color Correction, Bryan re-stages the moment when his subjects were the target of microaggressions. Here, Bryan talks about untangling internalized racism in his own life and work and why shooting Asian faces is relatively new to him.

How did you have the idea for your photo series?

My friend Mike Souvanthalisith was curating a photo exhibition at the restaurant Burma Lane and asked me to take part. Most of my work was fashion-based, so I thought I could do something more personal with a message I have not been able to express in fashion. In the creative world, Asians are mainly sidelined to be behind the scenes — not so much in front of the camera — whether that’s in fashion or film. I thought it would be cool to shoot a series in a cinematic way so Asians would be the protagonists.

You mentioned in our past conversations that you haven’t shot many Asian models in your fashion work. Why has that been the case?

I think there aren’t many male Asian models compared to females. Thomas, one of the guys in the photos, is one of the very few Asian male models in Melbourne. But to be really honest, I think I still need to take that step forward of choosing to shoot more non-white faces and trying to push that harder with the people I work with. Sometimes when an agency forwards me a list of models to shoot, there’s only one Asian face. Recently I had a chance to do a paid shoot for a publication in Asia. They straight up told me they wanted a Caucasian model because that is what’s seen as luxurious and prestigious, even though the photos would only be seen in Asia.

How did you feel to do a project where you only shot Asian faces?

It felt refreshing and true. It felt like something I’ve always wanted to do but didn’t realize.

How did your subjects feel about re-staging moments where they experienced racism and various microaggressions?

I think they were very open. A common response to these microaggressions is shock, or not saying anything because it’s happened so many times you can’t be bothered. You just know that sometimes — no matter how much you try to explain to a person why something they said is wrong — they may not get the point. It’s educational labor. So there was a general sense from everyone I shot like, “We’ve always had these things bothering us internally and now we have a place to express it.”

Tell me about the people in the photos. How did you link up with them?

The portraits feature Jenny Wang, Lei Lei K., Thomas Chow, Nick Teng, and Charmaine Salvacion. It’s a mix of people I follow online and who I’ve worked with before. Jenny was one of the first people I thought of for the series because she’s very vocal about race issues. Even her Insta name is so in-your-face (@asiangirlfriend). That’s how people seen Asian females.

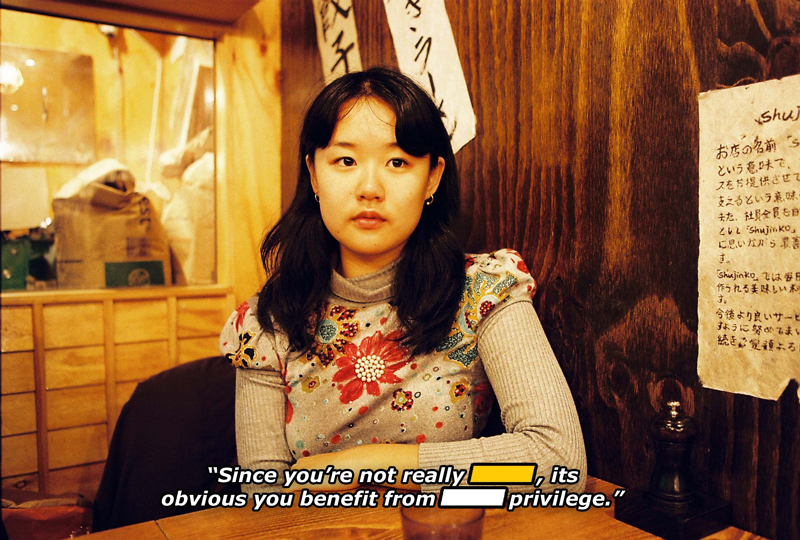

I imagine a lot of Asians in Australia instantly recognize these quotes. The one where Lei Lei is being told she isn’t Asian seems odd though… She obviously looks Asian. What was the context surrounding that comment?

Lei Lei’s old friend told her that. The implication was that she benefits from white privilege because she’s Asian but grew up in the West. But the sentiment was also that Lei Lei doesn’t look Asian. You look at her and you think how on earth could she be someone who looks white or even white passing? It’s jarring. Lei Lei was so shocked she just tried to move the conversation on to something else.

Charmaine’s quote about being told she looks half-white really struck me because the idea that being ‘half’ is more beautiful was quite prevalent among my Asian family and friends growing up.

Charmaine said that she heard that comment from a lot of Asian people. She said she initially felt a sense of pride to know people thought she looked half white — even though she isn’t — but as she grew older, she became more conscious and proud of her Filipino identity. She was like, “Why aren’t my Asian features celebrated in the same way?”

Since starting your creative work, have you come across your own prejudices that you’ve worked to overcome?

One clear memory was when I first started out. I was too self-conscious and ashamed to use my full name in my photography work. I would use a moniker instead. At the time, I didn’t know of other successful Asian creatives here. I had this mindset that if I used my real surname then people wouldn’t take me seriously or want to work with me. I think it took a long time for me to be like, “Screw it.” Now that I use my real name, it feels like I’m not lying to myself. In terms of people’s attitudes, I haven’t seen much difference. But hopefully that’s because I’m making better work.

Why was it important for you to make a series directly confronting racism and microaggressions?

Racism comes in all shapes and forms, it has no definitive identity. It could come from not just strangers, but friends or even loved ones. I think the general public is more used to the direct form, but not the indirect. This series is my way of subtly highlighting what may pass as offhand comments or compliments even. In reality, they are part of a cycle perpetuating ingrained stereotypes or assumptions people may not be aware of. I hope that it starts a deeper discussion of what race means to be an Australian and internal self-reflection.

Credits

Text Emma Do

Photography Bryan Tang