What happens to memories that have not been preserved in photographs? Spanish-born Berlin-based photographer Verónica Losantos tackles this question — while branching into the topics of recollection, family, veracity, and identity — through her compelling series Screen Memories.

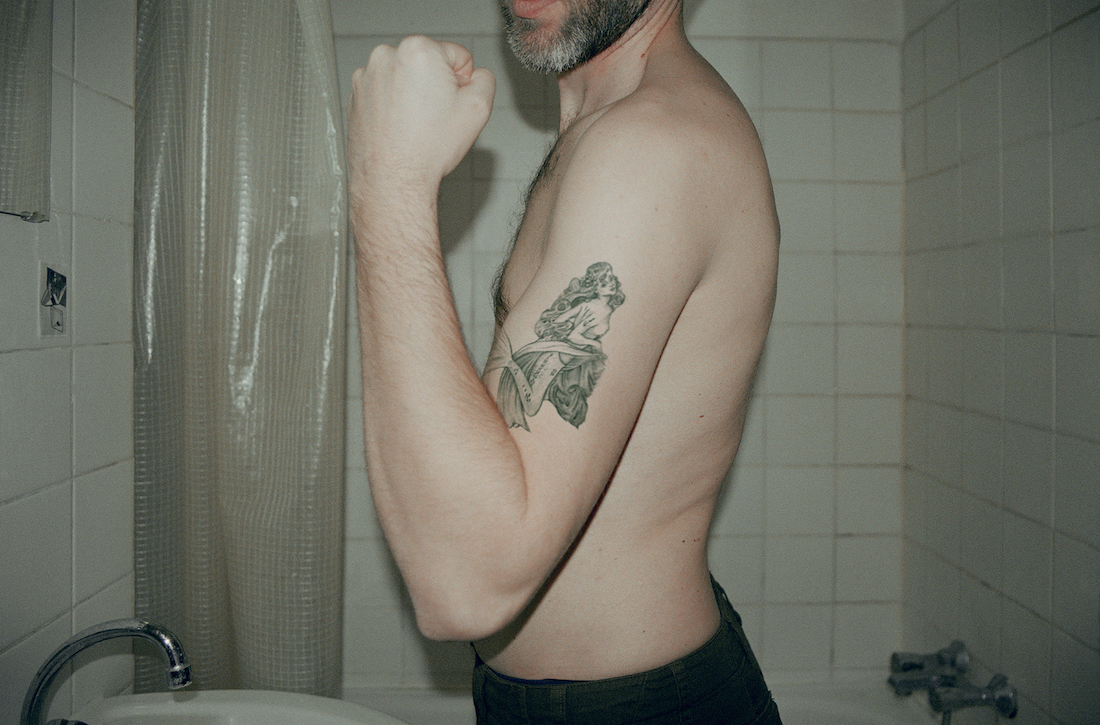

In the absence of family albums, Losantos was unable conjure up past moments shared with her father — moments that she wanted to access. Addressing the malleable nature of memory itself, Losantos consciously manipulated memories as a way to reconnect with and, in a sense, remedy family history. The result is a string of stirring visual clues that never lead to anything conclusive: soft blossoms, a record player, a tattooed arm, Russian dolls, a tree stump, a suit jacket, a toddler crying in the bathroom, a girl staring out of the passenger window of a car.

Using a principle articulated by Sigmund Freud, Losantos supplements her father’s long absence from her life with fabricated or altered depictions. Armed with an analog 35mm camera, she orchestrated a three-pronged approach: she reenacted memories she still had (casting friends as models); she restaged photographs of her father that she remembered, or photographs that he had taken; she also created purposefully fictitious memories. She doesn’t indicate which images fall into which category.

The project won the “Talents” Photography Contest in 2014, held by Berlin’s photography museum, and Screen Memories is currently on view at C/O Berlin (until April 24). Losantos discussed the role of psychology, the cinematic aspects of her work, and the universality of friction with family.

How did this series come about?

I read about the “screen memories” process that Freud had written about. He says children have two kinds of memories: important memories, and superficial memories. What happens is the superficial memories cover the important memories, which then transforms everything. I realized that when I look back at my childhood, there are a lot of black holes — a lot of things I don’t remember. It’s related to the fact that my parents got divorced when I was three years old, which was kind of traumatic. In the aftermath of trauma, you tend to forget more easily, because you want to forget the bad stuff — but the good stuff is also forgotten.

I started to think about how we could be influenced by photography to create our memories. When I was a child, you had the pictures printed, which you could hold on to. I didn’t have pictures of my father. I had a relationship with him until I was 12, but since then, no. Once my parents were divorced, the pictures were put in a drawer, and no one looked at them. To what extent did that affect my memories? I didn’t have pictures to refresh these memories. Then I thought: I could make screen memories in a conscious way, by staging memories. Also staging pictures I once saw of my father, or that he took of me. And then I just invented memories, filling that gap.

Behind the scenes, did you create a larger storyline, or did you keep it fragmented?

Memories are always fragmented. That’s why, in the exhibition, they’re different sizes — because they’re not the same size in your head, either. So I played with that. And they are not chronological. For the exhibition I just tried to “summarize” with the most powerful pictures that fit together, telling the story. I wasn’t sure if this topic would be too intimate, so I had to find a way to put it out there that was more neutral and universal. Because a lot of people have issues with their parents, especially divorced parents. It’s something they can identify with.

Some of your other series address cinema. How does that medium influence your work?

At the start, I wanted to go into cinema and study directing. I think cinema influences my pictures a lot — I always work in series, and I create a narrative so that people can ‘read’ the story. My pictures don’t work on their own; to get the meaning, you have to see it [as an entirety]. I work in a horizontal format more so than in a vertical format, which is also more cinematic.

Which photographers were important to you when you decided to pursue photography?

Nan Goldin is one of my favorite photographers. Another Spanish photographer is Cristina Garcia Rodero — she’s with Magnum. Wolfgang Tillmans. And, of course, when I started, Henri Cartier-Bresson, but that’s a typical reference for everyone!

Any new projects you’re working on?

I’m taking my next pictures in Spain about a village that’s underwater. Under Franco’s dictatorship in the 60s, he built a bunch of dams [for agricultural reasons], including one right where my grandparents’ village is. Now the village is underwater. Some years, when the water is low, you can still walk through the old houses in ruins. The people who were living there were forced to leave. Their only option was to go to the desert. Nobody wanted to go there, but Franco wouldn’t rebuild anywhere else for them. So I’m working on the memory of this old village, under the water, and how it is for these people to have to leave all their stuff — their houses, their gardens, everything — to live in another village, while seeing the dam each day. It’s a kind of mystical story.

‘Screen Memories’ is currently on view at C/O Berlin until April 24.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Verónica Losantos