The long shadows of destruction and defeat cast an apocalyptic pall on West Germany in the years following World War II. Cities had become uninhabitable, the landscape ground to dust, with millions forced to rebuild a nation forcibly divided by global superpowers. Faced with the unfathomable depravity of the Third Reich, many forged through the physical, economic and spiritual ruin that had reduced the country to ruins.

Growing up in the 50s, photographer Miron Zownir observed the widespread practice of cognitive dissonance that many adopted in order to survive. “Over 70% of the largest German cities were destroyed or significantly damaged during World War II, but depending on where you grew up and your sensibility, you might not have been aware of the impact it had,” Miron says.

“Most kids didn’t get much information from their parents or grandparents, and it was hardly a topic in school or among schoolmates. It’s hard to conceive that anyone could ignore all the ruins, veterans and widows, but growing up during peacetime seemed to make war so utterly abstract and insane for kids that it felt like something out of a movie. The German economic miracle made it possible to live and forget.”

But Miron could not unsee the world he observed as a youth living at his grandparents’ home outside of Karlsruhe, a former transportation hub for the Nazis that had been heavily bombed throughout the war. His neighbours included a despairing widow who engaged Miron in conversation every time he passed her window. At home, the strains of classical music could be heard on his grandparents’ Volksempfänger, a radio developed at the request of the Nazis, utilised to spread propaganda by the party. Miron recalls a couple of times a day, a man with a decidedly sinister voice from the Red Cross would drop by to read off the names of missing men and women.

Fortunately for Miron, the subject of war was not taboo among his family members, who were inextricably intertwined with the fate of Germany during the first half of the 20th century. Having lost two brothers in World War I, Miron’s grandmother blamed everything on the Versailles Treaty and became a Nazi sympathiser, while another brother and brother-in-law became SA (Sturmabteilung, aka Storm Troopers or Brownshirts). Miron’s mother was in the Hitler Youth and came to detest the Nazis.

After Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, his Ukrainian father’s family was deported to Siberia, where Miron’s paternal grandfather died of starvation. His father escaped, only to end up drafted into the Wehrmacht (Nazi army) soon thereafter. In April 1945, he was captured by the Russians and imprisoned once more in western Siberia. “I grew up in a strange world full of contradictions and unsolved mysteries that made me very early curious to search behind the obvious,” Miron says, who later became a conscientious war objector rather than serve in the Bundeswehr (West German army) during the 70s.

At a young age, Miron was drawn to the world of noir, staying up every Saturday night after his grandparents went to bed to watch a late-night Hitchcock, Renoir or Huston movie on television. But it was literature that held him spellbound, as novels by Kafka, Beckett, Burroughs, Bukowski, Nietzsche and Genet revealed a realm of imagination open to all willing to see. “They must have subconsciously accompanied me on my photographic adventures as if I was searching for characters, images and atmospheres that fascinated me in Crime and Punishment, Bleak House, Junkie or End Game,” he says.

Photography proved to be the perfect middle ground between literature and film, an unlikely discovery Miron happened upon in the late 70s after he borrowed his girlfriend’s camera and hit the streets of London, Berlin and New York. Drawn to the explosion of decadence and decay, Miron travelled to far-flung corners of the world, visiting Russia, Romania, Ukraine and Turkey during points of transformation and turmoil. “I started photography as an autodidact, spontaneous, and more or less out of compensation for not being admitted to film school,” he says. “I don’t have an adapted philosophy, ideology or religion. Sometimes, your judgment depends on facts and angles you might not even be aware of. As a photographer, I keep on documenting life beyond its obvious surface.”

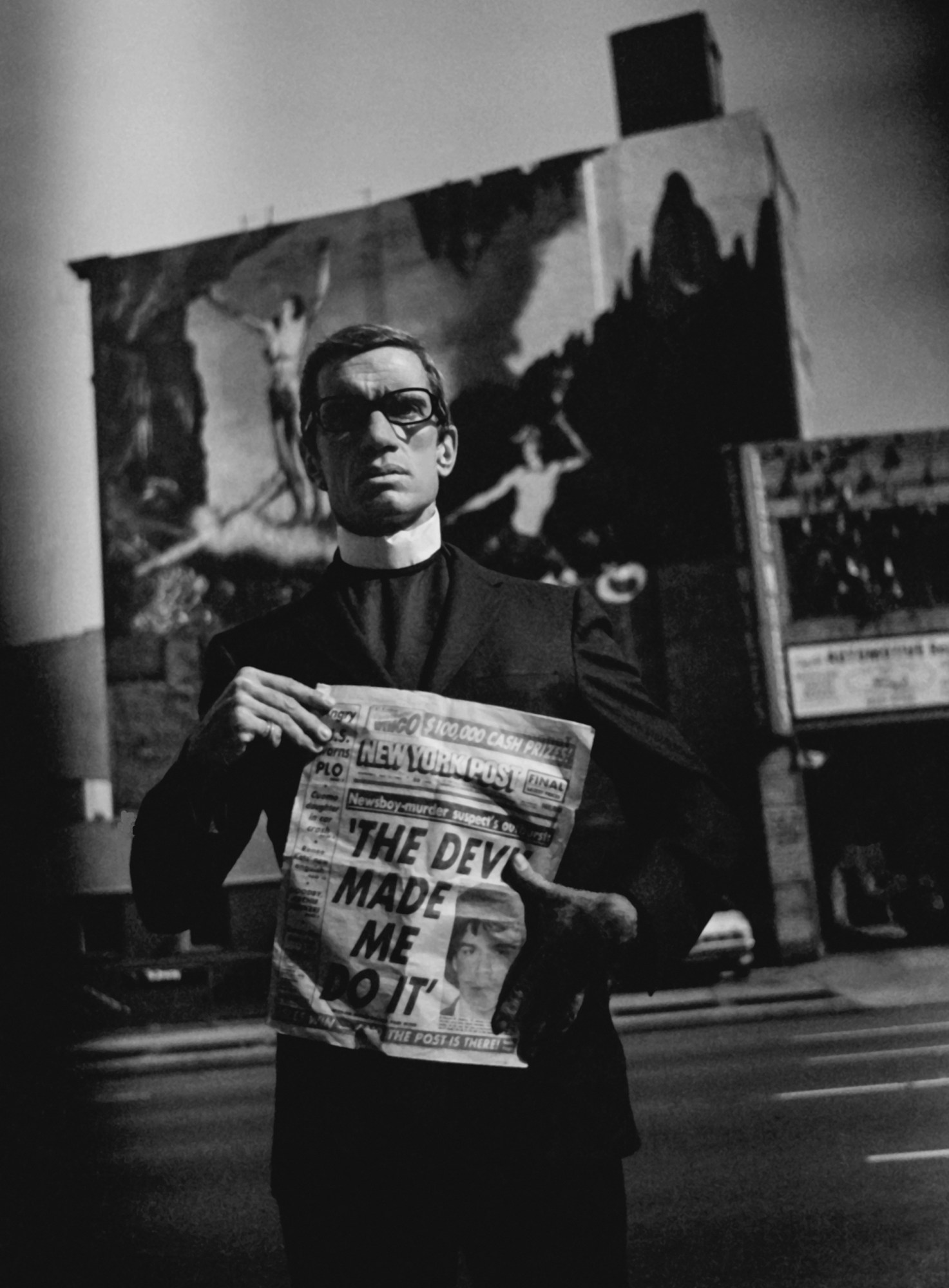

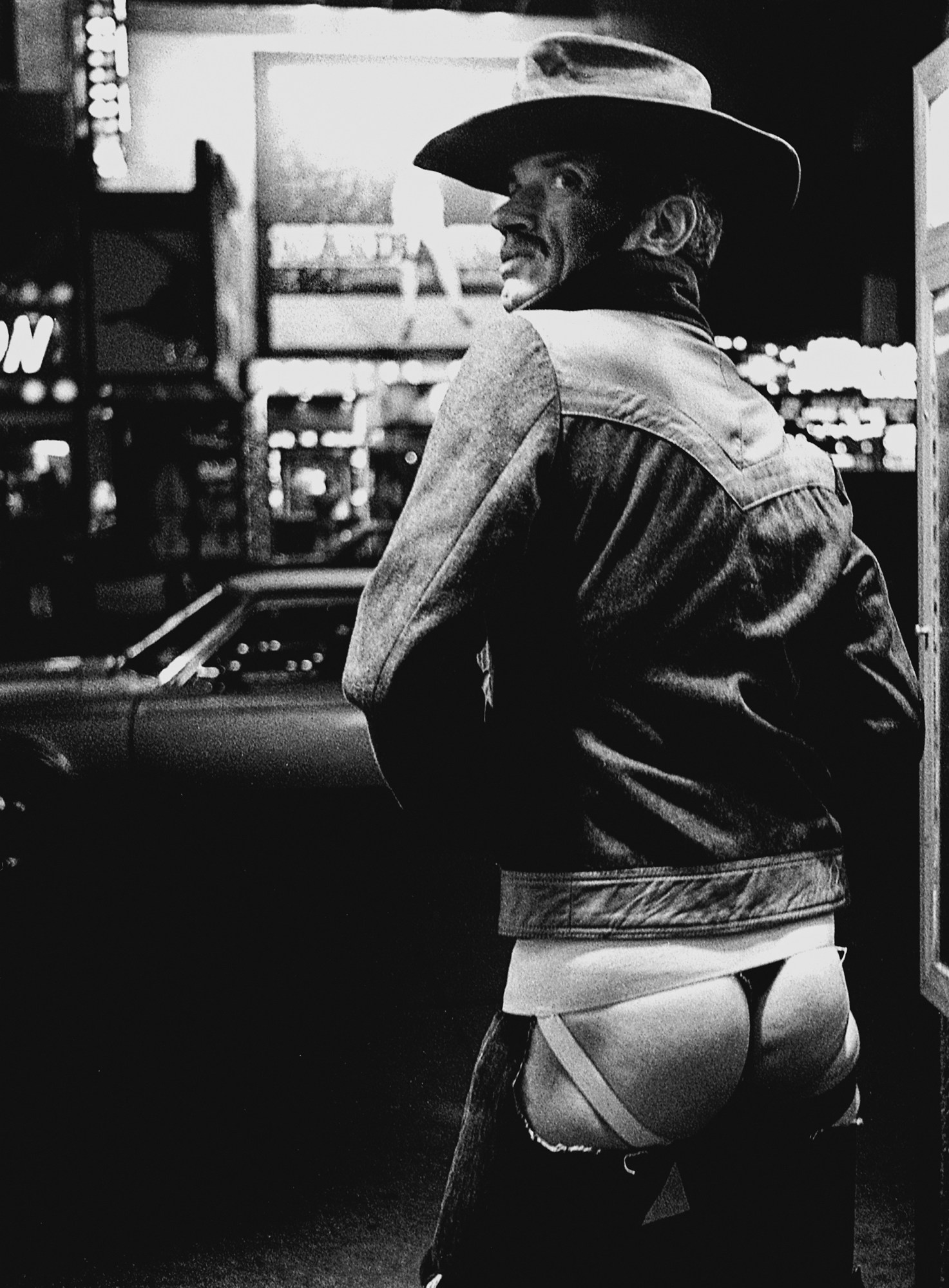

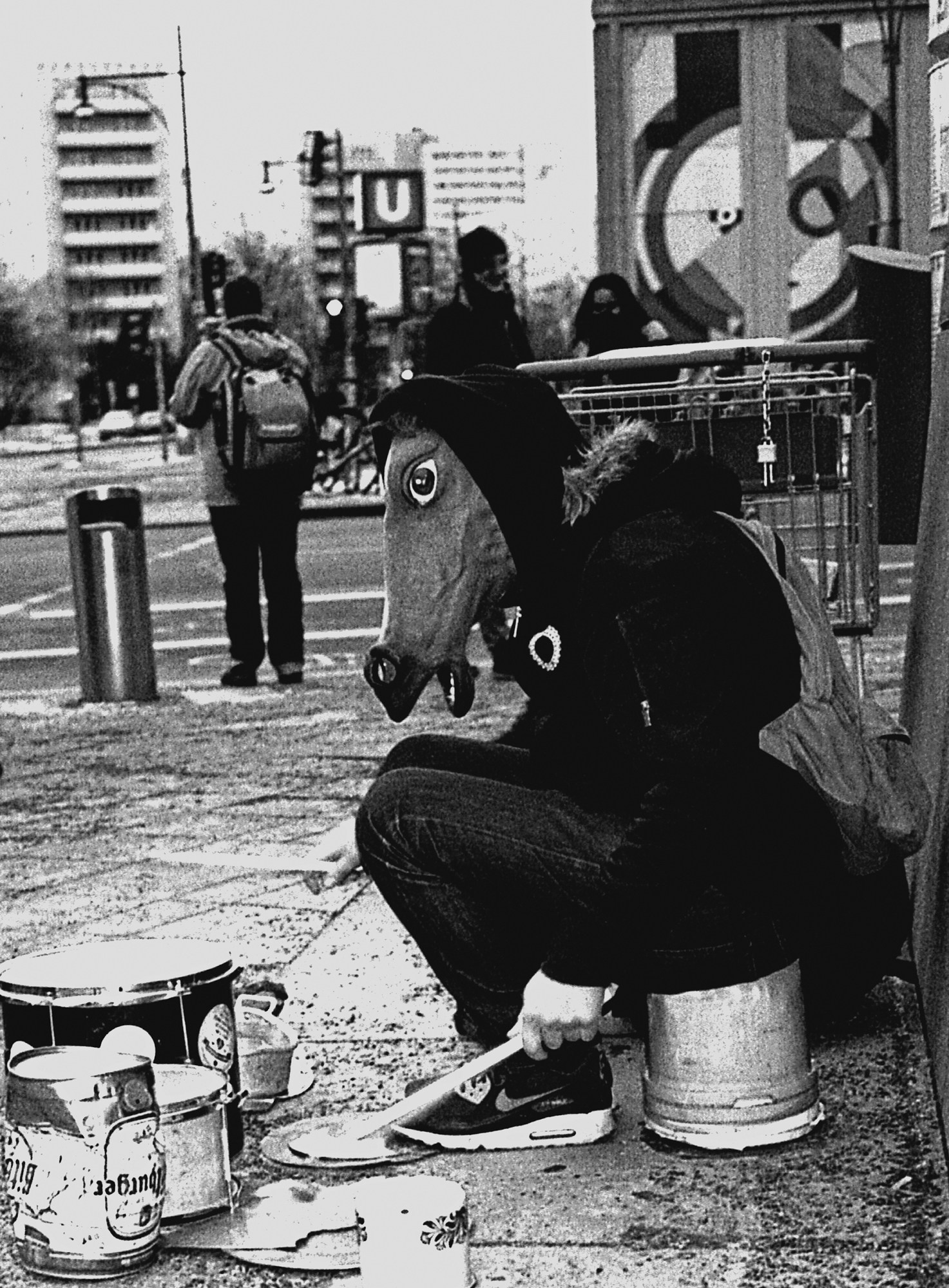

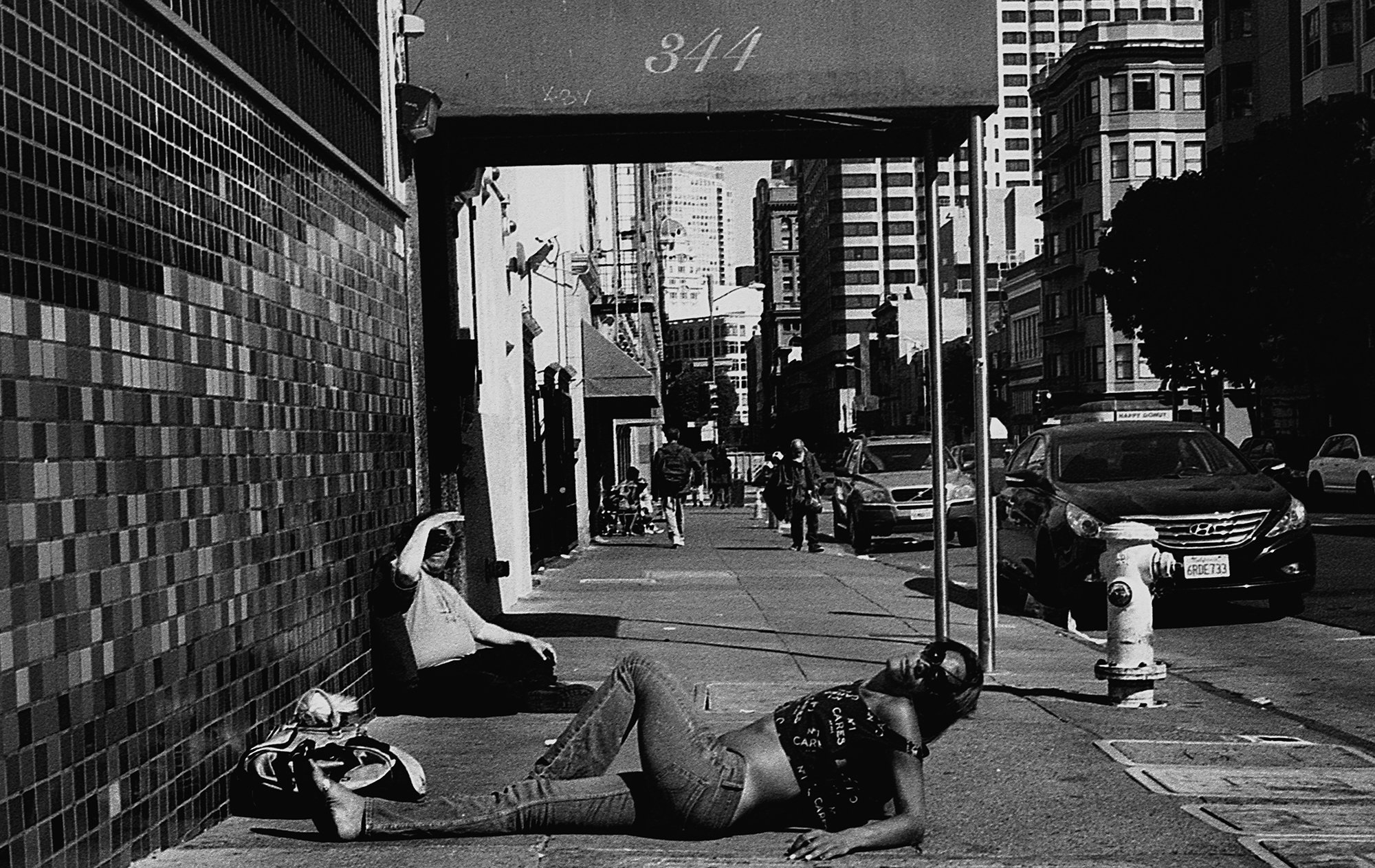

Now, Miron brings together scenes from the edge of the abyss in the forthcoming monograph, Walk Through the Fire (Gomma Publishing Ltd), to craft rending portraits of rebels, outcasts and iconoclasts living on the fringe and forced to fend for themselves. “Any big metropolis offers backdrops and hideouts or an atmosphere that provokes outsiders to challenge common sense, moralistic reservation or expected behaviour,” Miron says.

In a world that minimises, marginalises, and misrepresents the harrowing spectacle of trauma and the weight of responsibility, Miron’s photographs consider the deeper, more complex expression of humanity within these bleak circumstances. “The focus of my work is not mainstream suitable. It is a world many would like to ignore or even erase. But I can’t ignore the brutal reality of life or censor myself to please any expectations,” he says.

“Life masqueraded with false glamour has no magic for me. I was always interested in real characters, people on the edge fighting against all odds. Sometimes, my photos have this dreamlike quality, as if taken out of a nightmare. Sometimes, they are disturbing, poetic or brutal. But they are always reflecting authentic emotions and existential topics. In a way, photography expresses a kind of helplessness, watching someone in misery or pain, and you only can look, close your eyes, or walk away.”

‘Walk Through the Fire’ will be available to order from Gomma Publishing Ltd on 27 September

Credit

All images © Miron Zownir