I was 14 when I first asked for help with my mental health. I’d been struggling with depression and self-harm for several months, and had finally plucked up the courage to approach a teacher I trusted, to tell him I was cutting myself.

At first, the meeting was positive: he promised to call my mum and get me enrolled with the school counsellor, and I briefly felt the burden of struggling alone lifting, an almost physical reaction of weightlessness.

In the end, he did neither. He spoke to me about it once after that — keeping me behind in maths to bizarrely tell me I should stop self-harming so as to avoid scars on my wedding day — but never called my mum, never passed on my details to the counsellor. A similar experience followed with a GP (“all teenagers feel like this”), and it was five more years before I tried to get help again.

It’s been nearly 13 years since that first cry for help, and in that time my experiences have not been dramatically different. There was the therapist who kept insisting I couldn’t really be ill because, on the surface, I had such a good life; the GP who sent me away and told me to “come back in two weeks” if I was still feeling suicidal; another who stopped me mid-consultation to ask if I’d considered giving up smoking instead. And, just last week, the A&E staff who sent me home after I’d sought help for plans of suicide with a printed out webpage entitled “are you feeling the strain?”

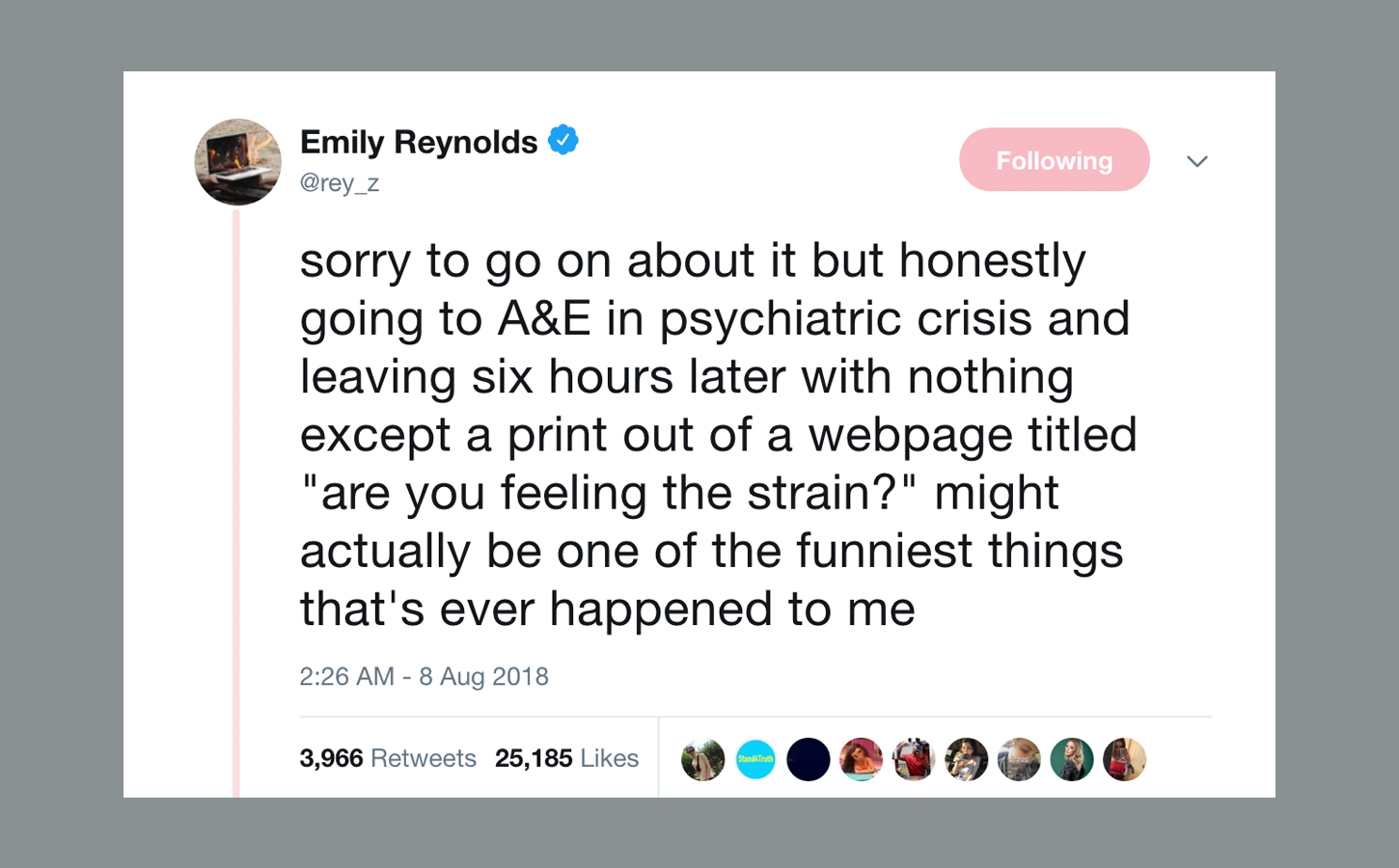

The scenario so ludicrous it became genuinely funny to me, so I tweeted about it. Having been in and out of mental healthcare for over ten years, and spending the last three years of my life writing about it, I was expecting a few replies confirming that my experience was not unique. But a week later, the tweet has had over 25,000 likes and nearly 2,000 replies, and the extent to which my story resonated shocked even me.

It’s particularly egregious when you consider how prevalent the ‘Time to Talk’ narrative has become in recent years: the idea that to get help for your mental health you merely have to ask for it. When help isn’t there, what are you even asking for?

There were hundreds of stories of crises ignored, of people passed from team to team with no resolution, of people presenting at A&E intent on killing themselves, only to be sent away with no support just hours later. Some of the healthcare professionals showed real callousness, which obviously shouldn’t be ignored — there undeniably needs to be better training for those working in non-mental health specialisms. Acknowledging this does not undo any of the great work the NHS does.

But many of the issues were structural — and for anyone who’s been paying attention to government cuts over the last few years, this shouldn’t be a surprise. A lot has been made by the government — and particularly by Theresa May — of a so called ‘parity of esteem’ between mental and physical health. But despite the fact that spending on mental health is at a record high, analysis from the Royal College of Psychiatrists earlier this year found that trusts have actually been left with “less funding in real terms” than in 2012, due to inflation and increase in demand.

Quantitative research also backs up the experiences shared underneath my tweet: in 2015, the Care Quality Commission found that only 14% of patients felt they had received appropriate crisis care.

There’s been a drop in new mental health nurses too, meaning those who are working are faced with overwhelming caseloads — partly linked to the abolition of NHS bursaries for new nurses. The number of beds for mental health patients has also decreased by 30% since 2009 — so it’s no surprise that I and others were unable to receive any inpatient care, even in crisis.

Even attempts to address rising mental health problems in young people have been stalled because of lack of funding and staff. In 2017, the government proposed a waiting time cap of four weeks for children and teenagers needing help. In reality, though, these measures wouldn’t come in until at least 2021 — again because of cuts.

The stories that were missing from the thread are probably the most important: the stories that can’t be told because the people who might tell them are now dead. Hundreds of people told me stories about partners, friends and family members who had taken their own lives after failing to receive help; some had attempted suicide over and over again, and still found it impossible to find anyone who would listen to them. Mental health is now so often a topic made twee and easily digestible by brands or the media that we forget that in many cases it is literally life or death.

It’s a stark reminder that mental illness should not be treated as a political football or as a cute on-trend message for brands to take advantage of. There are thousands of people out there who are unable to cope, who are suffering and even dying. These people need help that simply isn’t available to them — access to care in crisis, ongoing community support, therapies. It’s not enough to be given a bit of paper and sent home; it’s not enough to be placed on a waiting list for months on end; it’s not enough to be told you’ll get a call back and never getting that call.

Above all, it’s not enough that we merely survive. We should also be able to have lives that are fulfilling and full of joy and, at the moment, that’s not always possible. It’s vital we demand that changes.