When New York-based model and creative director Lucia Yao Gioiello was a kid, she spent time between Indian meditation and Korean Daoist groups with her Bronx-born Italian father, who was a bit of a hippie. Her Taiwanese mother left to pursue a career in dance choreography when she was young, which meant Gioiello didn’t have the chance to explore that side of her heritage. Growing up looking physically Asian, she found herself identifying with the region’s culture more generally and “trying to grasp what that means.” Fast-forward several years, her interest in the similarities and differences around Asia have led to her cross-cultural art book series FAR—NEAR, which aims to broaden perspectives about the continent and move away from stereotypes. Through fashion editorials, critical essays and photography, she assists in an Edward Said-inspired “unlearning” of “the inherent dominative mode of understanding the region”.

“It was just seeing a gap in representation,” Gioiello explains. There are a variety of indie glossies like Nii Journal and Black Boy Feelings that document the black experience, but when it comes to exploring what it means to be Asian, not only Asian-American, the offerings were limited. “I wanted to create a platform for artists that doesn’t pigeonhole them or dictate what they should be creating or focusing on.” In the two volumes she’s produced so far, “On Movement” and “Taste—Distaste”, the work of acclaimed writers and international artists (including Iranian photographer Shirin Neshat, Tbilisi-born David Meskhi, The Beijing Opera, the designers behind South Korean streetwear brand IISE, and 73-year-old Japanese photographer Hitoshi Fugo) sit alongside a plethora of emerging Asian creatives.

But the first task in creating FAR—NEAR was identifying where the borders of Asia reach and extend to. “When you look at Europe and Asia, it’s one massive land mass and the borders between the two continents are merely political,” Gioiello says. As the home to 60% of the world’s population across around 50 countries, it was important for the editor to broaden what mainstream culture considers to be Asian — “allowing the people who contribute to the book to freely express themselves without limiting what they talk about.” In the United States in particular, she says, the term Asian is often over-simplified to mean people from China, Japan, Korea or India — a limitation that perpetuates stereotypes.

There’s a tendency to exoticise Asia and Asian people, Gioiello adds. Japan is often “idolised as a mysteriously perfect aesthetic place. People see China as this massive, hectic country with its own set of rules. While Southeast Asia is a tropical wilderness.” In his 1978 book, Orientalism, Said examines the history of how the West, particularly the British and French empires, constructed a thought process that focused on this “otherness” of Asian society, beliefs and customs. By using “the basic distinction between East and West as the starting point for elaborate theories, epics, novels, social descriptions, and political accounts concerning the Orient, its people, customs, mind, destiny and so on,” he writes that the West were able to better secure their stability and supremacy.

In a lot of ways, this has led to a fetishisation of Asian women across the continent, Gioiello explains, and the idea that they’re simultaneously submissive and ornamented. “I was reading this really interesting article about porcelain skin being the most idolised skin in most Asian countries,” she says. “And how it can be compared to Chinese porcelain and the pedestal that the West put Chinese and Korean ceramics on, and how that’s directly related to the objectification of Asian women in the West.”

But FAR-NEAR doesn’t only wish to dispel stereotypes. It also celebrates Asian talent and artists aren’t obligated to speak about their heritage if they don’t want to. The first volume “On Movement” uses photo and text to explore the act: gestures, transportation, the political and artistic. These include a series of images from Les Noces, a dance her mother choreographed for the Century Contemporary Dance Company that she founded in Taiwan, which merges influences from the East and West, and is set to a Stravinsky score. “Including her in the first book felt natural,” Gioiello says. “It was a way to get closer to her and the realm she’s in.”

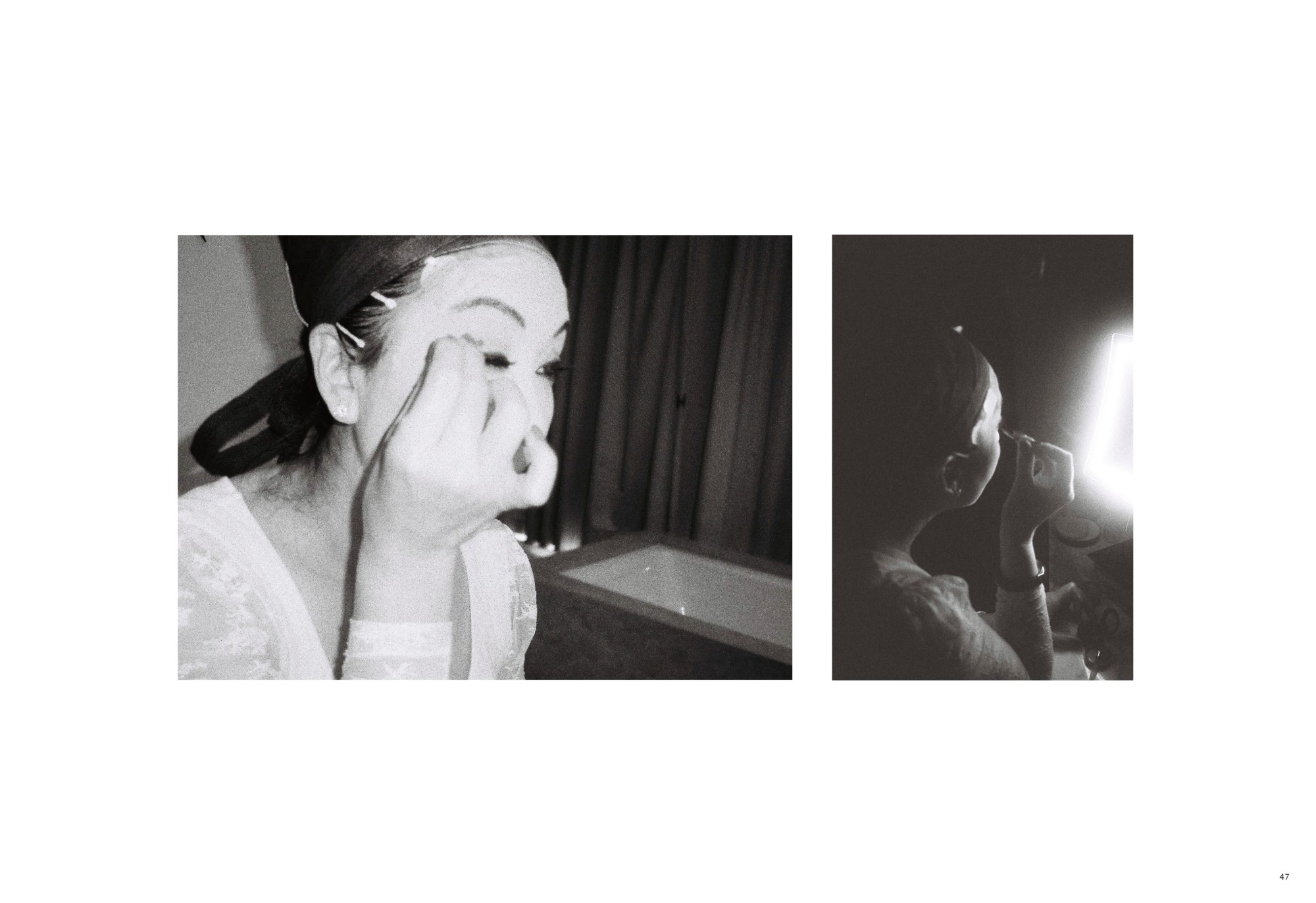

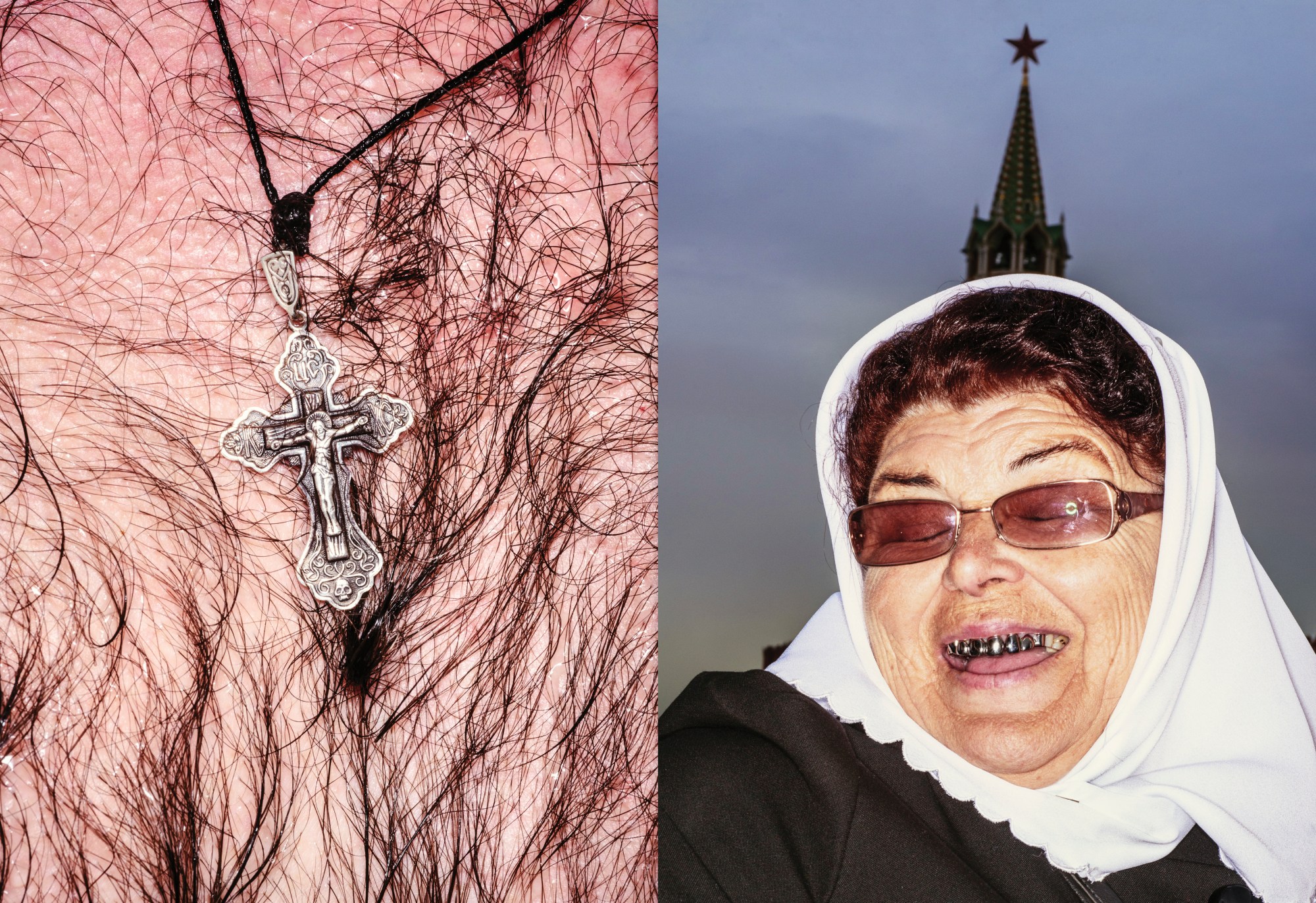

Between photographs of New Delhi Pride and a Russian grandmother wearing grills, there’s a series of intimate portraits by Dorothy Sing Zhang of her mother getting dressed for a performance with the Beijing Opera. Editor Ariana King’s essay The Pushed and The Pulled explores the different words used for migration and immigration — particularly with regards to the Rohingya Muslims who have fled Myanmar to neighbouring Bangladesh. She contrasts their status as illegal immigrants to her own emigration to Japan not so long ago. She was referred to as an “expat,” or someone “living abroad”, which highlights the disparate social and cultural dynamic of labelling a person differently based on where they are coming from.

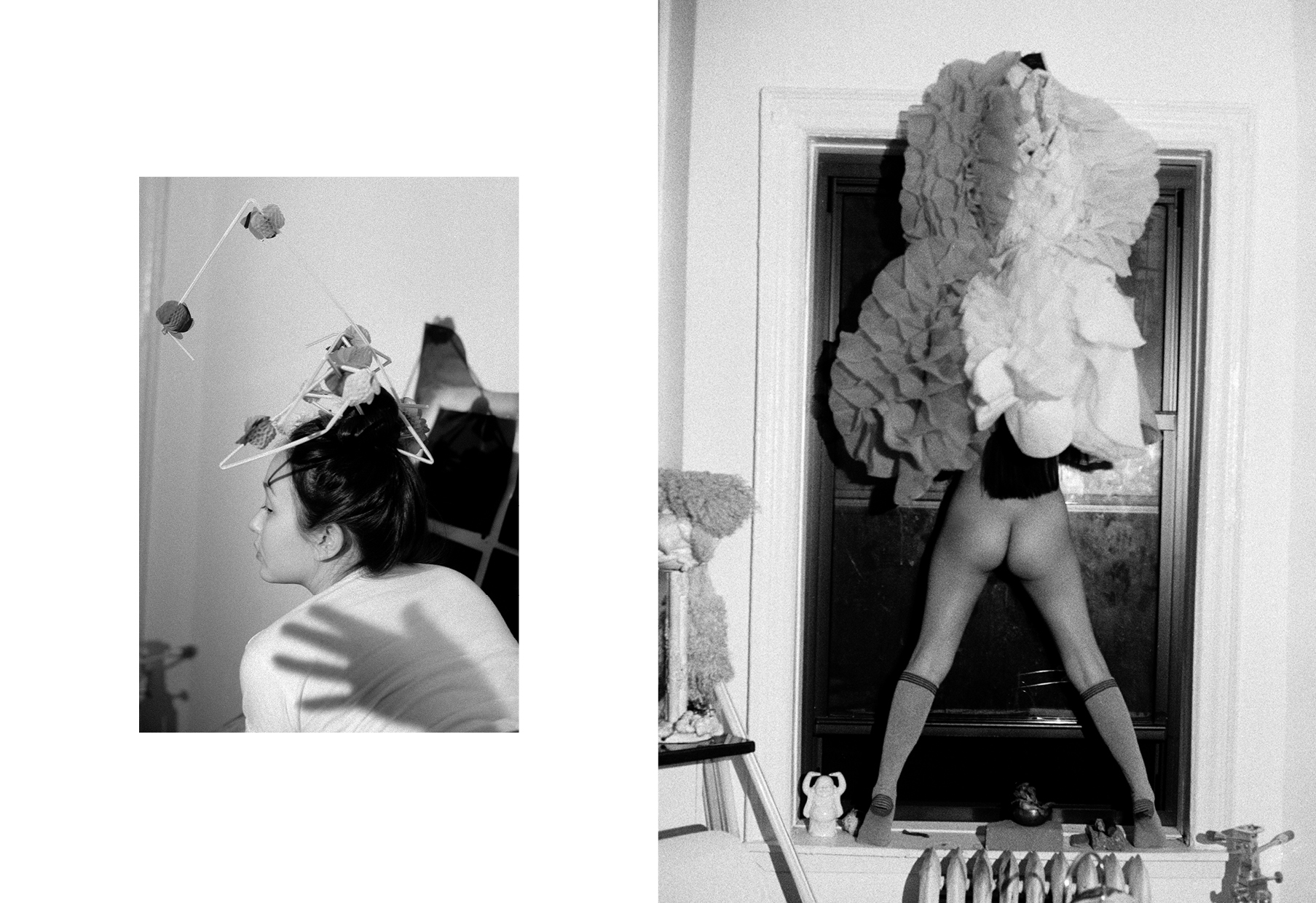

The second issue titled “Taste—Distaste” rolls out stories on aesthetic preferences, as well as foods (and recipes!) central to festivals and family life. One photography series by artist Hitoshi Fugo’s showcases the cast iron pan he uses to cook for his family, while another titled “Breakfast with Pixie” captures the artist Pixie Liao eating a papaya from her boyfriend’s crotch, flipping the fetishised narrative of eating sushi from a naked woman’s body. There are interviews and essays on everything from Fukushima-irradiated mushrooms to pickle-themed art exhibitions and diasporic fashion senses. “We explore the flavor polyphony of a modern creative culture representing the Asian continent,” opens Gioiello’s editor’s letter. “Developing over time through what we choose to filter and absorb as our own, what might taste good to us might be to the distaste of another. Taste is subjective.”

“Fades and Braids” explores identity through different hairstyles — the ways they can change how you feel and how you are perceived. When Gioiello was young, her father would chop her hair into a blunt, chin-length bob with bangs, and people would comment that she looked like a “Chinese doll.” In response, she rebelled and refused to cut her hair for 15 years. The long hair gave her a look that was “exotic and tropical”, with Italian waves and Taiwanese colouring. “In the last 5-7 years I’ve cut my hair really short and I’ve felt so much more myself and less defined by my hairstyle,” she says. “I think it gives a feeling of liberation to change something that really does transform the way you look.”

Along with the editorial, “Fades & Braids” was released as a short film directed by Amber Grace Johnson, who has previously collaborated on music videos for Jorja Smith and Kali Uchis, as well as Rihanna’s Savage x Fenty line. Filmed with New York-based hair salon Shizen Brooklyn, it featured creatives from a variety of upbringings discussing their Asian identity through their relationship with their hair. One girl wearing a soft yellow outfit with bleached blonde locks recalls, “My mum used to always tell me in our culture, for a woman, our hair is our jewellery, and the way we wear our hair is the way we wear ourselves.”

Ultimately, what Gioiello hopes is that someone picking up FAR—NEAR will have no idea that the book as a whole is focused on solely Asian art. In the West, if you’re a contemporary artist you’re not usually categorised by your ethnicity, but when you’re from an Asian country you’re defined by that culture; too often othered, fetishized and plagiarized. She wants the annual book series to become a space that can celebrate work by Asian creatives that is open, broad and varied, while still having that loose theme around it. “If you see many different things and somehow they’re all connected, I think that’s a really good message to put across,” Gioiello says.