A video game that puts players in the role of a curious young girl exploring the idea of sex is being celebrated for its cultural significance. Based on the designer’s own experiences as a girl — how do you Do it? allows players to use plastic dolls to investigate sexuality, and helps them understand or remember the clumsy, often confusing discovery of what sex “is”.

It will be playable at the V&A’s show on contemporary video games opening in London later this year — exploring how gaming is pushing boundaries in radical ways, the first major exhibition of its kind in Europe — but how do you Do It? has its origins somewhere far more humble: at a bar, over a beer.

Games designer Nina Freeman was talking with a teammate at a bar during the Global Gaming Jam in 2014 — an annual hackathon focused on game development that takes place in different locations every year. “I don’t remember the exact theme for the games we had to create,” says Nina, “but it was something about projecting yourself onto objects.”

She was telling her friend that she used to “hide under my bed and pretend my Barbie dolls were having sex — I wanted to know how it worked, so I would role play it, ‘playing house’ almost. I would always hide under my bed when I did it because I didn’t want my mom to see”.

It was such a strong memory, with such an “interesting story in which to find a mechanic”, she says, that the team ran with it and created how do you Do It? to present to their fellow gamers. The result — a short, simple vignette game — was something people seemed to connect with immediately, many saying they too had experimented in the same way when they were young.

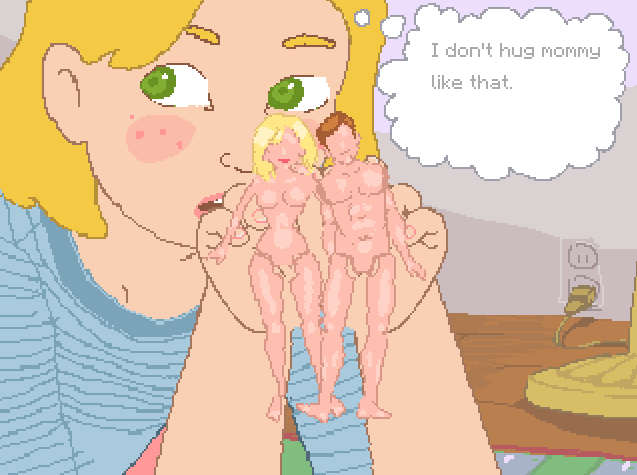

The game’s protagonist — an 11-year-old girl — puts her Barbie and Ken-esque dolls in various positions, asking curious questions — ones we can all relate to — like, “What is a ‘floor hug?” and wondering why the window steams up during Titanic‘s iconic car sex-scene, as she imagines the dolls as Rose and Jack.

“It felt true to life and that people were relating to it on a personal level,” says Nina. “Then when we put it online it sort of blew up because I think it’s one of those stories that a lot of people have but don’t feel as if they ‘should’ say out loud because it’s taboo. But once it’s out there they’re like, ‘Yeah — it’s totally true.’ That’s the vibe I got from it. Any time you have a story people can relate to, it can open up a conversation. When you see something on your own level it makes people feel more comfortable to open up about their own thoughts or stories.”

“We released the game and didn’t do much else with it, we let it have its own life. I know it’s been used it classrooms, I don’t really know for what exact purpose — I’d be happy for people to use it for anything useful.”

Coming originally from a poetry background — mentored by New York poet Charles North — writing about ordinary life and personal topics, Nina says her games are rooted in that tradition of story-telling and intimacy: games are an extension of her poetry and creative background, rather than a separate entity. That in itself sets how do you Do It? apart from much of the contemporary gaming landscape.

Marie Foulston, co-founder of the UK’s first indie game event (the Wild Rumpus) and Curator of Videogames at the V&A, says the game is important for many reasons. “Even just having a game that’s this short and simple and easy to interact with is actually quite radical in itself,” she explains, talking about its inclusion in the gaming show. “As these days a video game is often something that can take upwards of 16 hours to play.”

The aesthetic of how do you Do It? is radical too. Marie speaks about how the general trend of video games from the 1990s to 2000s was “this drive” toward hyper-reality, as the received wisdom was that the more realistic the appearance the more players could relate to the game. “Actually when you look at broader arts and design that’s not always the best way to engage people with different experiences,” says Marie. “Sometimes it can be quite abstract. That’s not to say that games like how do you Do It? aren’t deeply personal and deeply relatable — they are.”

She says contemporary games designers like Nina are pushing away from this and exploring other ways of engaging players. They’re also proving there’s potential for video games to explore personal, social and political issues — such as conversations around sex and sexuality.

“From a feminist perspective it’s important too,” says Marie. “When we think about video games and sex, normally one leaps to ideas of objectification, treating sex through the lens of titillation. What this game shows is that video game stories around sex can be incredibly personal. When we think of games we often think of entertainment and often miss their potential to explore complex subjects and in a way only games can — as they’re active rather than passive.”

Through curating the show, Marie has come across a lot of anecdotal evidence of marginalised communities using games to explore issues and their own identities in a potentially safer space than IRL. Robert Yang is another designer featured in the V&A show, exploring sexuality through video games and looking at representations of gay experiences. He made The Tearoom, for example, locating players in a public bathroom to explore “anxiety, police surveillance and sucking off another dude’s gun”.

His work looks at the objectification of the male form, and the idealisation of a specific type of physical masculinity (often white, muscular, and found in big blockbuster video games), as well as exploring issues of intimacy and consent.

Phoenix Perry has mentored and collaborated with Nina Freeman for many years. As well as creating physical games and user experiences, she lectures at Goldsmiths, University of London on physical computing and games, and advocates women in game development, as well as bringing new voices into the industry. She and Nina co-founded Code Liberation Foundation in 2012 — an organisation that teaches women to program games for free. Since then they’ve worked with over 2,000 women between the ages of 16 and 60.

Her main interest is in human relationships and intimacy, and how games can reinforce interconnectivity. Bot Party, for example, her current game, is about holding hands in groups to strengthen friendships. “Mentoring Nina was more like just being a friend and helping her out with my connections,” says Phoenix. “My main interest was championing her to others because I saw something in her that needed space and resources to grow. Clearly, it was just the right thing to do. Life so often doesn’t give breaks to young, talented women. I was in a position to fix that for once in my life, so I did.”

Mike Driver — games critic, author, and lecturer in popular journalism — thinks games like how do you Do It? can be educational as well as radical pieces of art. “We see schools using Minecraft to encourage creativity, communication and sharing among young children. The game has an Education Edition. Games can, through their stories and the interactions that progress them, teach people a lot of things in a safe environment.

“Role play is very important to children, and games can absolutely be a useful tool in that process. To walk in the shoes of a game character can tell you a lot about a certain kind of person, about nationality, sexuality, race and gender. I’ve never been a teenage lesbian, but playing Gone Home gave me an insight into what that must be like, when your parents can’t relate to the type of person you’ve grown to be.”

Mike — like Phoenix — sees games as being personal and as works of self-expression: “The medium is just as valuable as a means of individual expression as painting, novel-writing, whatever. So we see games like That Dragon, Cancer and Papo & Yo (and so many more) that address quite personal yet universally relatable issues — in these instances cancer and alcohol abuse, respectively. Night in the Woods looks cute, full of cartoon animal characters, but tells a story of spirit-crushing depression quite unlike any I’ve watched, read or played.”

As video games curator Marie says: “Nina herself is a hugely important designer, she is a very radical games designer”. how do you Do It? was just the beginning of her body of work drawing on personal stories and small, intimate scenes and worlds.

In another of Nina’s games, Cibele, we explore her relationship with a man she met via multiplayer adventure game, Final Fantasy XI, where players form online clans to slay monsters and discover treasure. Cibele gamers access a version Nina’s own computer desktop from the time of this relationship — folders full of her own real photos, poems and live journal entries — and a version of the Final Fantasy game they played together, audio clips of the two speaking on the phone and film sequences of Nina taking selfies to send to him.

Rather than a desktop, players are accessing an intimate snapshot of a time in Nina’s life, a 19-year-old girl falling in love.

Nina’s game Kimmy sees gamers play Dana, a young girl in 1968 who babysits a smaller child named Kimmy. The adults around them are busy and wrapped up in their own stories, so the children are left to their own devices. Players spend after-school hours with Kimmy, Dana and their friends. In Ladylike, players control a conversation between a teenage girl and her disapproving mother during a drive to the mall, talking about school, boyfriends and clothes.

With games like how do you Do It?, contemporary games designers are pushing forward the art form of video games, realising their potential to tell small, personal stories and foster greater understanding between people; in short, they’re becoming more human.