London-based Canadian musician Tiberius b might be relatively new to carving out their liberatory, queer sonic landscapes, but their stage moniker has been with them since before they were even born. “Tiberius is something my parents used to call me when my mother was pregnant. They thought I was going to be a boy,” says Frank Belcourt. “It was a name that was predetermined before they knew what my gender was going to be.”

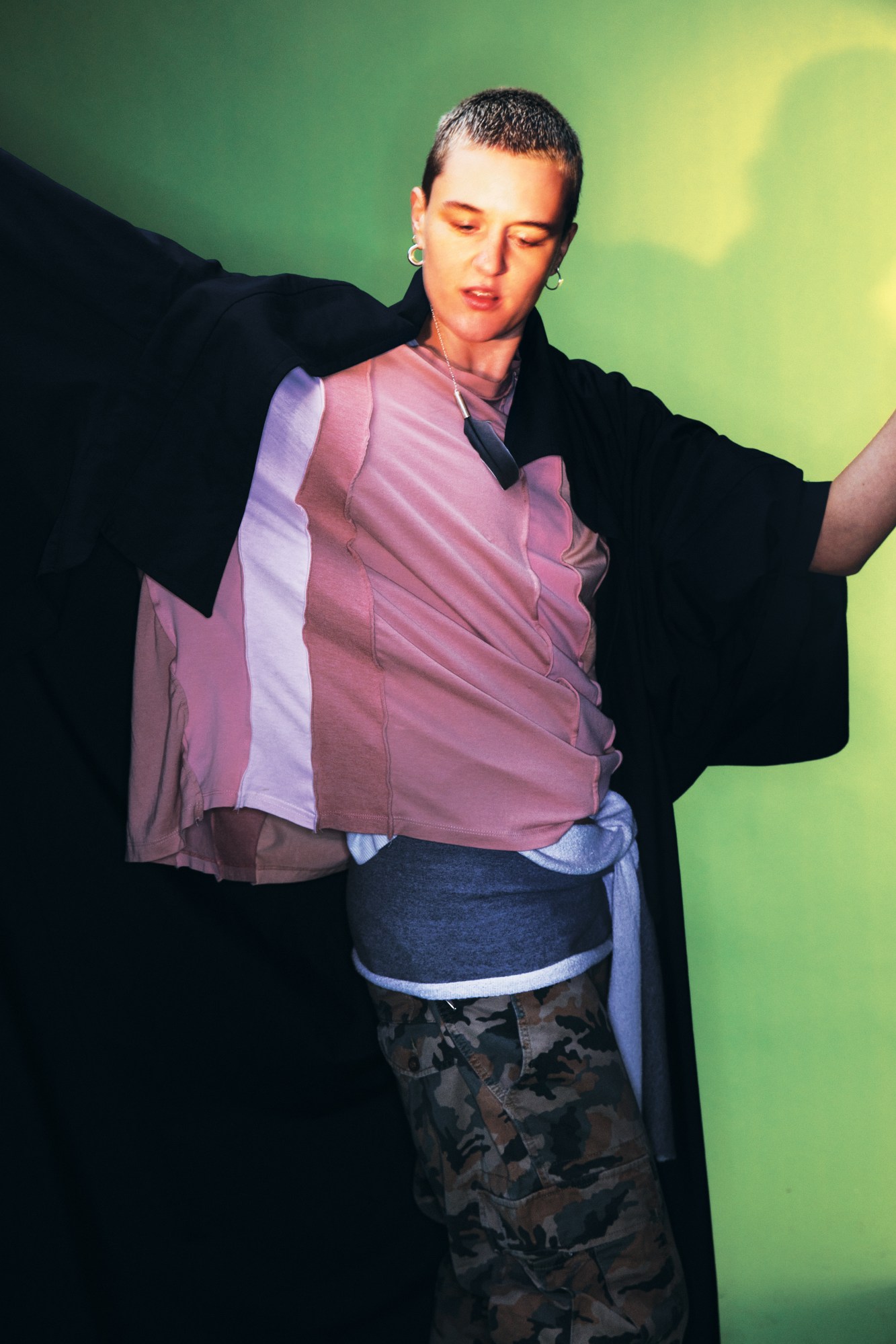

The universe of Tiberius b lies adjacent to Portishead’s 90s trip-hop melancholy, and Frank’s vocal textures have shades of Cocteau Twins’ playful candour. I meet them just after the release of their second EP, DIN: a beguiling record that draws confidently from familiar sounds yet flings its evocative lyricism and imagery into an uncertain, sexy future. It’s a euphoric, six-track immersion into grief, sex, trans beauty and disobedience; a tribute to the grime and grunge of London, the city it was created in.

Fittingly, on the balcony of Somerset House, Frank and I are surrounded by the chevaliers of DIN and London alike: the much-maligned survivalist and unlikely muse, the pigeon. In the music video for “Jetski”, the second track on DIN, Frank sings while writhing with euphoria on the floor: a flock of pigeons take flight, perch on their drummer’s cymbals, and shit on everything, including Frank’s blonde buzzcut. “Take me home / make me come / over, and over, and over…” Frank sings. It’s a dirty, electric paean to sexuality. “I was clicking into myself in a really deep way,” they say of the song and its video. “I had been waiting my whole life to feel the way I felt in that moment, and it was explosive.”

The song is about an encounter Frank had with someone during that awakening. “You’re a packet of salt, and I’m a jetski,” they sing on it. “Maybe in their eyes, at that moment in time, I was quite fun and shiny,” Frank guesses. “Pretty fearless, and not afraid to take up space.” And move fast? “And move fast!” they concur, laughing.

Frank has described DIN as “the noise of [their] life”; a “moving towards real, raucous relations”. “The songs are about relationships I fostered here, and it’s messy and intense and kind of gross: I wanted it to be about London in some way,” they say. And so Hamish Wirgman, who collaborates with Frank on the art direction for Tiberius b, suggested pigeons as a symbol. “I was like, that’s fucking perfect. Pigeons, they’re normal and average, but also so not,” Frank says. “Flight is the ultimate emblem of freedom, you know? And there’s a sort of symbiosis with queer migration from rural places to cities. Pigeons originally made homes in high cliffs, which is why they transferred so well to buildings, and thrive.”

An even more potent symbiosis emerges here with Frank’s own life, which has always straddled the extremes of urban and rural. Their parents, after meeting at a stained glass workshop in London, dated for three months before accidentally getting pregnant – and made the “crazy decision” to move to a remote island in British Columbia. Frank was born and raised in the woodlands and beaches of Cortes Island: reachable only by ferry, via another ferry, via a drive across Vancouver Island, via another ferry. When they lived there, it had a population of only 900 people. Their father became an oyster farmer, then a carpenter.

“I felt very aware of the intense beauty that I was surrounded by,” Frank says. “The beauty of that particular area in Canada is quite ominous and heavy. Where I’m from, everything is big and severe. It feels dangerous and hot: sexy hot, not hot hot,” they laugh. It was a blessed existence, but a lonely one, too. “You have to have quite a rich inner world to compensate. I got into music through that isolated feeling: it made me feel close to something. Music made me feel un-alone.”

Their exposure to music was a mosaic, curated solely by the people around them. “There was no shit on Cortes. My only access to culture of any kind was through whatever my parents had,” Frank says. They dove into their parents’ CD collection from the UK, and became “obsessed” with Blur’s Parklife at the age of three. Trip-hop was introduced to them via their dad; soul music via their mother; alternative music via the skateboarders (“a skate park got built to give teenagers something to do on the island”) they hung out with.

The arrival of a Mac set something into motion in Frank’s household. Toying with preset loops on GarageBand, Frank wrote their very first song at the age of 12, and began performing their music at high school whenever and wherever they could. “I had a really amazing teacher that recognised I was writing songs,” they say. He put Frank in a separate room, ran back and forth between two classrooms, and taught them how to use Logic 9 in secret. “He was like, just make an album,” they recall. And so, at the age of 15, Frank did: “I made artwork for it with my friends, assembled physical copies at my house. I was hustling it out of my backpack,” they say, smiling. (Sheepishly, they won’t reveal the album’s name.) “And I bought a laptop with the money I made.” It’s the laptop that Frank uses to this day; they’re still using their high school teacher’s copy of Logic 9 to make music, too.

“I changed my name when I moved here, because I wanted to start again”

After high school, Frank left Cortes Island for Vancouver to pursue a career in music. They put out a few albums under their birth name, but after five years, a reset was needed in 2019. “I came to London for my cousin’s wedding, and just didn’t get my flight back,” they say. Holding UK citizenship, they decided to just stay in London. The trip became a fortuitously timed upheaval. “I changed my name when I moved here, because I wanted to start again,” Frank says. In parallel with deciding to remain in London, the musician began to learn about non-binary identity: Tiberius b was born.

From here on, it sounds almost mystical. During lockdown in 2020, Frank was staying with their grandmother in Dolwyddelan, North Wales. They were cycling through the valley on a neighbour’s bike one day, nursing existential anxieties about the future, only to return to their grandmother’s house to find that Zelig Records (Mark Ronson’s label, home to King Princess) had reached out about “No Smoke”. An intimate, haunting track, it was the first single Frank ever released as Tiberius b. “This guy that worked at Zelig found it through my friend’s Instagram story,” Frank says. “They were like, ‘We love ‘No Smoke’, we want to re-release it as a single. Do you have some more demos?’”

Frank found themself in the middle of North Wales with the opportunity of a career, but no guitar. They asked around – their grandma’s neighbours; neighbours’ friends – and the next day, a man appeared on their doorstep with a BC Rich Warlock. A black-bodied guitar shaped like an “X”, its dramatic, shark-like silhouette is famous among metalheads. “It was so fucking bizarre, this old guy bringing me this metal guitar. I think the guy from Slipknot plays that guitar,” Frank says, laughing. Zelig loved the demos, and Frank wrote their first EP, Stains, with that very instrument. The EP’s artwork features a man standing in a river, handing them a BC Rich Warlock.

“The place my grandma lived in Wales really resembled where I grew up, and I think that was helping me with the music,” Frank says about writing Stains. “When I feel good about what I’m making, there’s a deep connection to that early self — and those crucial moments where you fall in love with a sound for the first time.”

Frank searches for truth, but not so much for answers. “I wonder what it would feel like / the best day of my life / safely basking in the limelight / with freedom from my desires?” Frank asks on “Twofer”, a sullen track about their relationship to the language of queerness, “feeling boxed in by classification” and surgical alterations to the body. How do they feel about the trajectory between Stains – a record that thematically explored heartbreak and the idea of a queer coming-of-age – and the more brash, free and questioning DIN?

“Stains felt like the beginning. I’d always had jobs my whole life – restaurant jobs, shitty jobs – and I’d never been able to fully dedicate my time to music. It was really overwhelming,” Frank says. “With DIN, it actually settles into itself. It was coming faster, coming out better.”

That confidence is sonically palpable on DIN, but it’s perhaps most vividly embodied in Frank’s videos for the project, which thrum with a swaggering, rebellious physicality: something that can only be described as gender-disobedient euphoria. “HHB”, which stands for ‘Hot Handsome Beautiful’, is an anthem celebrating trans beauty, but Frank has a renegade vision of what that means. Spreading their legs in a pencil skirt, sheer stockings and heels, they take a long, powerful piss on the side of the road in the music video; they then sing to their own reflection in the puddle of yellow urine, like a debauched Narcissus.

“I think it’s important to be gross.”

“The thing I really want to express through my work is a degree of ugliness, because there’s a lot [about being trans] that is not fun, not pretty,” they say. “I also think ugliness in a sexual context is the heart of sexiness. I feel pop music dismisses that more than it did in the past. There is this attraction of commercial entities to cash in on queer art, and that’s really nasty to me,” Frank adds. “I think it’s important to be gross, and sort of wink at that.”

Yet the gem of DIN is its astonishing first track, “Delicate People”. It’s in many ways an outlier on the EP – a quiet, devastatingly powerful song about grief that Frank describes as “a bit of a black sheep, maybe because it’s so sad”. Written a few days after a friend’s death in a freak accident, it contemplates what it means to share our ephemeral time here with other, fragile bodies. “I feel like I’ve seen a lot of people go. My mom was really shocked at how much death me and my brother have experienced,” Frank says. “I wrote [‘Delicate People’] in Wales because I went there for my grandma’s funeral, so it was kind of like I was going back to Stains. I wrote it on the Stains guitar.”

Frank has just written another album, which hones DIN’s nuanced, expansive emotional scope even further. “It’s less about needing to tell myself a story to make a situation feel okay, and more so just saying things that feel good to say,” they say, charting where their music is leading them. “I’m asking a lot more questions, more so than telling myself answers. It’s open, forgiving, and curious.” As we speak, they gesture at a pigeon taking flight into this messy city that’s now their home – towards a destination that’s wildly, almost beautifully unknown.

Credits

Photography Aidan Zamiri