If the world wide web came with a rule book, surely “do not ask the internet if you are attractive or not” would be plastered across the first page. Yet, we’ve been asking strangers to rate our appearance online for over a decade. The infamous subreddit r/AmIUgly turned 10 this year, and now teens on TikTok are outsourcing opinions on how to become better looking in a new viral trend.

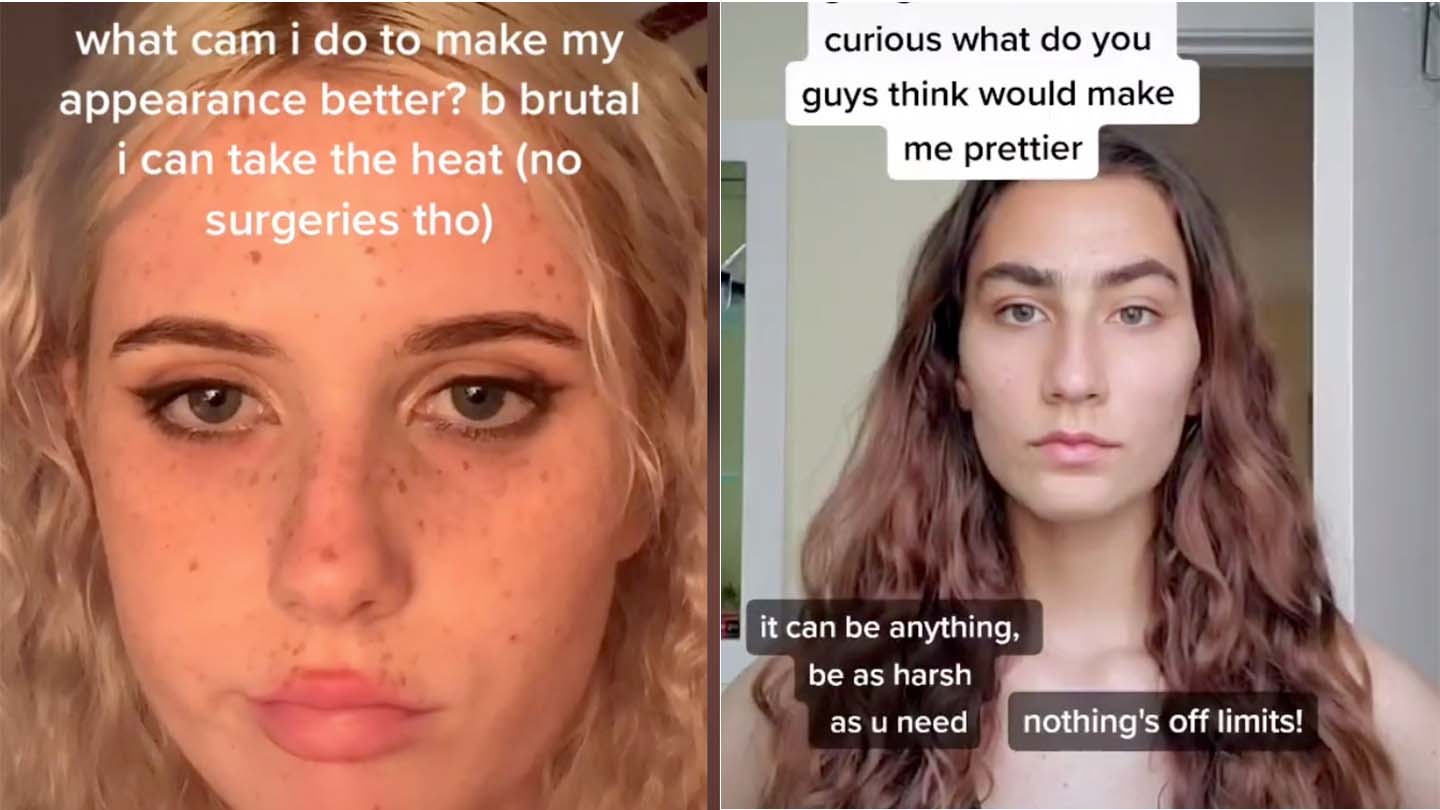

Tens of thousands of people, some as young as 12 are filming themselves in the style of a casting self-tape, canvassing TikTok’s 800 million monthly users for tips on looking prettier. ‘What can I do to be hotter other than plastic surgery,’ one caption reads, ‘please be mean I can take it, I’m willing to change anything’. Although the feedback offered on r/ AmIUgly was often remarkably nice, TikTok is less forgiving. ‘Lip fillers’, someone comments. ‘Maybe a smaller chin???’, reads another. ‘You are just boring get over it’. On a video posted by a sixteen year old girl, one person comments ‘3rd degree burns’. ‘Surgery’ chimes another. Annabelle, a 17 year old TikToker from Houston, Texas, posted her own video asking for advice after a particularly boring evening spent in her bedroom. Safe in the knowledge that she had only 20 followers, Annabelle posted the video and went to sleep. When she woke up, it had made it onto TikTok’s chaotic For You Page and clocked up 50,000 views. The video has since been watched over 230,000 times and amassed more than 2,500 comments.

“At first, a lot of [the comments] were just telling me to do my eyeliner and my makeup better,” Annabelle says over the phone, “then all the ones saying I needed plastic surgery kept coming in and I was like, ‘Okay, that hurt a little. For a couple of days I was down, because I was like ‘damn, am I really that ugly?’”

One reason for the excessive negative feedback could be TikTok’s lower age bracket, as 69% of its users are between 13 and 24 years old, while 25 to 35 year olds make up 41% of Reddit’s user base. “There were some comments on the video that pointed out some insecurities that I’d never noticed before,” Ragan, a TikToker from Pennsylvania, explains. “It wasn’t advice like ‘do this makeup’, ‘change your style’, it was like ‘your eyebrows are too far apart’, ‘your eyes are too big’. Stuff you can’t really change.” Despite receiving plenty of compliments, the 16 year old says she finds it hard not to fixate on the critiques. “Ever since I’ve gotten [the comments] whenever I do my makeup I always look at my eyebrows, because that was one thing people said.”

Kitty Wallace, a trustee of the Body Dysmorphia Disorder Foundation, defines BDD as “an anxiety disorder where the individual will focus on a perceived flaw in their appearance.” Wallace emphasises ‘perceived’ because, she says, it’s less about the flaw being imaginary and more about how perceivable it is to others. For people with BDD, the anxiety caused by the flaw is disproportionate to the flaw itself. While it may not be the case for everyone suffering with BDD, Wallace believes that “some people will be able to trace back the onset of their BDD symptoms to one comment.” 17-year-old Alina, a Canadian TikToker with 83,000 followers, screenshots the meanest remarks left on her videos. “I guess it’s negativity bias?” she admits. “Our brains expect to hear the worst.” After posting her own TikTok asking for advice, Alina received a comment scrutinising every millimeter of her face, including her ‘gonial angle’ (???). “That kind of disturbed me,” she admits, “with the thoroughness, they used a lot of very technical terms”.

Anyone who has spent longer than they care to admit on TikTok will know that the app is split into several elusive planes. There’s elite TikTok, straight TikTok, political TikTok and for those chosen few, even frog TikTok. But the app’s recent proliferation of fasting app adverts along with the steady rise in pro-Ana communities signal a dangerous undercurrent of body-shaming content that is pushing closer to the surface. “My whole For You Page is like these skinny, indie girls in their low-waisted jeans,” Annabelle sighs, “and I like those videos because they’re aesthetically pleasing, but sometimes I’m like ‘damn I wish I looked that good’”. While Wallace insists social media doesn’t cause BDD (the first case of BDD was diagnosed way back in 1891) she believes it can “definitely exacerbate symptoms”. “One of the symptoms for BDD – everyone will have an element of this but with BDD it can be all-consuming – is comparison making,” she says. “Scrolling through endless pictures of Instagram models or people who’ve had cosmetic procedures will make that person feel very insecure.”

r/AmIUgly centered around a simple yes or no question, but asking TikTok what you can do to become more attractive opens up a world of painful subjectivity. In the end, the answers say almost nothing about your own face and everything about our narrow, euro-centric beauty standard.

On every video, demands for darker, straighter hair flood the comments. Thousands call for lash extensions and lip liner combos in enthusiastic caps-lock. “It was basically all the same,” says 22 year old Jes from Indiana, who’s TikTok has 5.5 million views and 1.4 million likes. “It was all eyeliner, darker eyebrows, big lashes or extensions”. They’re prescribing a type of Instagram Face – a term first coined by Jia Tolentino in the New Yorker – an e-girl version of Madison Beer or Cindy Kimberly onto anyone that asks. “It’s a young face, of course,” Tolentino wrote back in December, “with poreless skin and plump, high cheekbones. It has catlike eyes and long, cartoonish lashes; it has a small, neat nose and full, lush lips.”

Some have gained confidence through the trend, either as a result of the compliments they’ve received or after experimenting with the advice offered. But it’s a “risky” strategy according to Wallace, who flags up reassurance seeking as another symptom of BDD. “The problem is the more you seek that reassurance, the more you need it. And then when you don’t get it, you feel paralyzed and you can have a big collapse in your confidence.” Instead, Wallace advises trying to limit those conversations instead of engaging with them. “There are so many other elements of ourselves that are important,” she tells me, “the more we focus on appearance, the more insecure we are about it.”