If you’re a live music fan on TikTok, it might seem like something is going very wrong at gigs at the moment. Plaguing artists like Phoebe Bridgers, Mitski, Billie Eilish and Harry Styles, the TikTok audience seems freshly obsessed with queuing, as trends showing off how long fans have waited outside to get the perfect photo seem to encourage wait times of twelve-plus hours. Filling FYPs with a worrying cycle of queue content followed by clips of more and more artists pausing their shows for fan safety issues – one seems to feed directly into the other.

“We joined the queue at 7 am, we wanted a good view”, 18-year-old Libby told me about Phoebe Bridgers’ show in Birmingham where the first person arrived at 3 am, adding that she recently “queued around 11 hours for Lorde.” Written into decades of fan culture, both fans talk about the atmosphere of the queue, socialising ahead of time in a sacred ritual that goes way back to the Beatlemania of the 60s. But after TikToks of Phoebe herself staring out into the crowd with a look of worry, and tweets about how it was a “shit show”, the chaos doesn’t seem to be going down the same way in 2022.

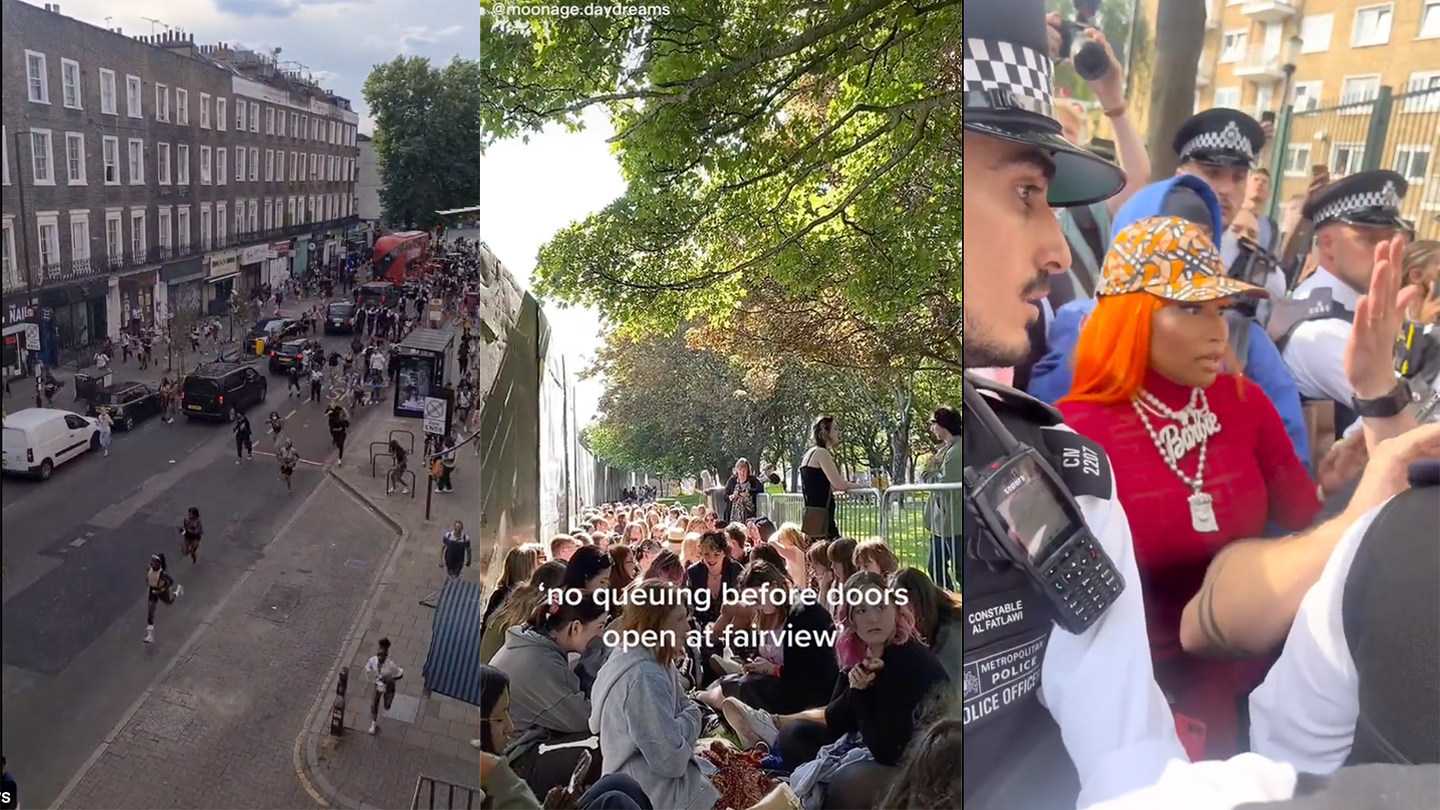

“Birmingham was bad,” says 17-year-old Poppy, who queued from 2pm. “At least three people fainted, someone vomited and someone else had a seizure so it had to be stopped quite a few times.” The situation is not unique to the UK. In Antwerp, the Sportpaleis recently came under fire with Billie Eilish fans calling the security “inhumane”, blaming the venue for people fainting 12 hours before the doors even opened and event staff clocked in. Despite sharing a blog post of ground rules 24 hours prior calling for people to not arrive too early, bring food and water, and prepare for hot weather conditions, it seems like another example in a clear pattern of early queues leading to worrying shows – begging the question of whether fans heading down early is always a safety concern.

“It is,” says Alice James, a production manager and lecturer in crowd management and event safety at the University of Westminster. As well as common concerns exhaustion or dehydration, Alice worries mostly for young fans queuing from the night before or the early hours of the morning; “especially when venues are in cities where you never know how safe they are.” “The question remains,” she adds, “do we have a duty of care to make sure that security are there overnight? And where does that extra financial cost go? Is that the artist’s responsibility or the venues?”

Caught up on a boundary between different bodies’ duty of care, venues like The Roundhouse, which recently dealt with long queues for Mitski and Lorde, said they now have “24-hour security” to ensure there are “safety and welfare measures in place as soon as fans start to queue.” But even in cases where venues appear to be implementing measures to work with fans, it never seems to be enough.

In a post-Astroworld space where artists stopping their shows now gain news coverage and the topic of crowd safety still spirals around social media, it feels all too easy for fans to simply blame venues and security without considering their own responsibility. It’s a frequent debate between young and old fans on TikTok, with commenters often alleging issues at shows are down to venue failures, claiming they oversold gigs or overheated the venue. Given the strict regulations in place, however, Alice doubts this. “Across the board for venues in the UK, we are very good at health and safety,” she says. “Security companies take it seriously and wouldn’t oversell tickets.” But still, fans blame them. It seems like the mainstream conversation about crowd safety has emboldened fans to discuss a topic that people like Alice spend years studying and training for. As an issue that goes way beyond good venues or bad venues, the current conversation doesn’t give space to the nuance or necessary discussion of fan responsibility.

For Alice, safe shows require continual “reassessing crowd management and safety plans” with considerations of site, weather and demographic. COVID also still needs to be a consideration; “after two years of not having any shows, people have slightly forgotten how to behave”. With the behaviour of returning crowds being flagged up at the International Live Music Conference, you’re not crazy for thinking the vibe has been slightly off post-pandemic. As the largest crowd many people had been in since 2019, Glastonbury faced backlash over the decision to increase capacity by 3% this year, leading to people calling the crowds “dangerously full, relentless”. While Glastonbury defended the decision by telling us it was “approved by Mendip District Council”, is it right to be upping crowd sizes while people are still reacclimatising to being in them again?

And who is there to teach new crowd members how to behave? Thanks again to the pandemic, a new demographic of gig-goers are suddenly turning up in hordes with no experience of gig etiquette beyond what they see online. The digital obsession seems to form a vicious cycle. “People want to be earlier than [they were for] the last show,” Libby said in an attempt to explain the frenzy at Phoebe Bridgers gigs. As fans attempt to outdo each other, Alice agreed that social media is making the frenzy worse; “It’s FOMO. People don’t want to feel like they’re missing out on a part of something, especially something as important to people as music. There’s this one-upmanship like, ‘how big of a fan are you? I went down at 1 am. Well, I was there a week in advance.’ It makes it difficult to dissuade fans not to queue when their peers are exhibiting that behaviour.”

Queuing early, passing out from exhaustion and stopping the show – it doesn’t feel like a winning recipe for gaining the love of your favourite artist. But when it occasionally slips into a way to get their attention, a whole new issue opens up. Scrolling across TikToks of fans getting free merch after passing out at shows, or incidents like Alice experienced with artists offering to meet unwell fans after the show, “while it’s well-intentioned, it opens up a bit of a can of worms in that if people think they’ll get to meet the artist, the whole copycat thing can and does happen.”

And when fans like Poppy are saying explicitly that an artist not stopping their show for someone fainting “definitely would affect [their] feelings towards them”, it places not only the burden of crowd safety but reputation maintenance onto the shoulders of musicians who just want to do their job. But annoyingly, it seems like only the artist could fix it.

“I think only the artist saying something would have an impact,” Alice says, “because certainly the venue and the promoters aren’t going to make a difference.” But the discussion of crowd safety and fan behaviour is a tricky one. No artist would want to seem ungrateful for people showing them love, yet as the issue seems to spiral on regardless of venues like Old Trafford calling for Harry Styles fans to not queue and security trying their best to handle it when they do anyway, musicians might need to come forward as the voice of reason or be stuck in the consequences of their own fans’ obsession each time they have to stop a show. Risking upsetting the people that made their careers and who dedicate their time and money to seeing them, the necessary conversation isn’t an easy one.