The sickle is coming down hard and fast on the neck of the film critic. Once a storied profession, taken seriously and paid fairly, the industry has now, critics would argue, turned its back on them. Last month, it was claimed that the French arm of Warner Bros screened Barbie for so-called “MovieTok” social media figures, influencers and select critics before the review embargo, meaning many of the country’s most prestigious titles – amongst them Cahiers Du Cinéma and Libération – didn’t see the film until after hundreds on social media had already sung its praises. As one freelance critic Eric Vernay tweeted: only “journalists who got the Barbie logo tattooed on their forehead” got invited to the pre-release screenings.

Of course, Barbie performed well regardless, even if Cahiers’ critic did hate it. But negative reviews have barely had a correlating impact on a movie’s box office success anyway. The Meg 2: The Trench was released earlier this month; dubbed “a completely anonymous bag of lukewarm McDonalds” by one critic, its Rotten Tomatoes score (aka Critics’ Consensus) currently sits at 28%. Despite this, it will double its budget in ticket sales this weekend.

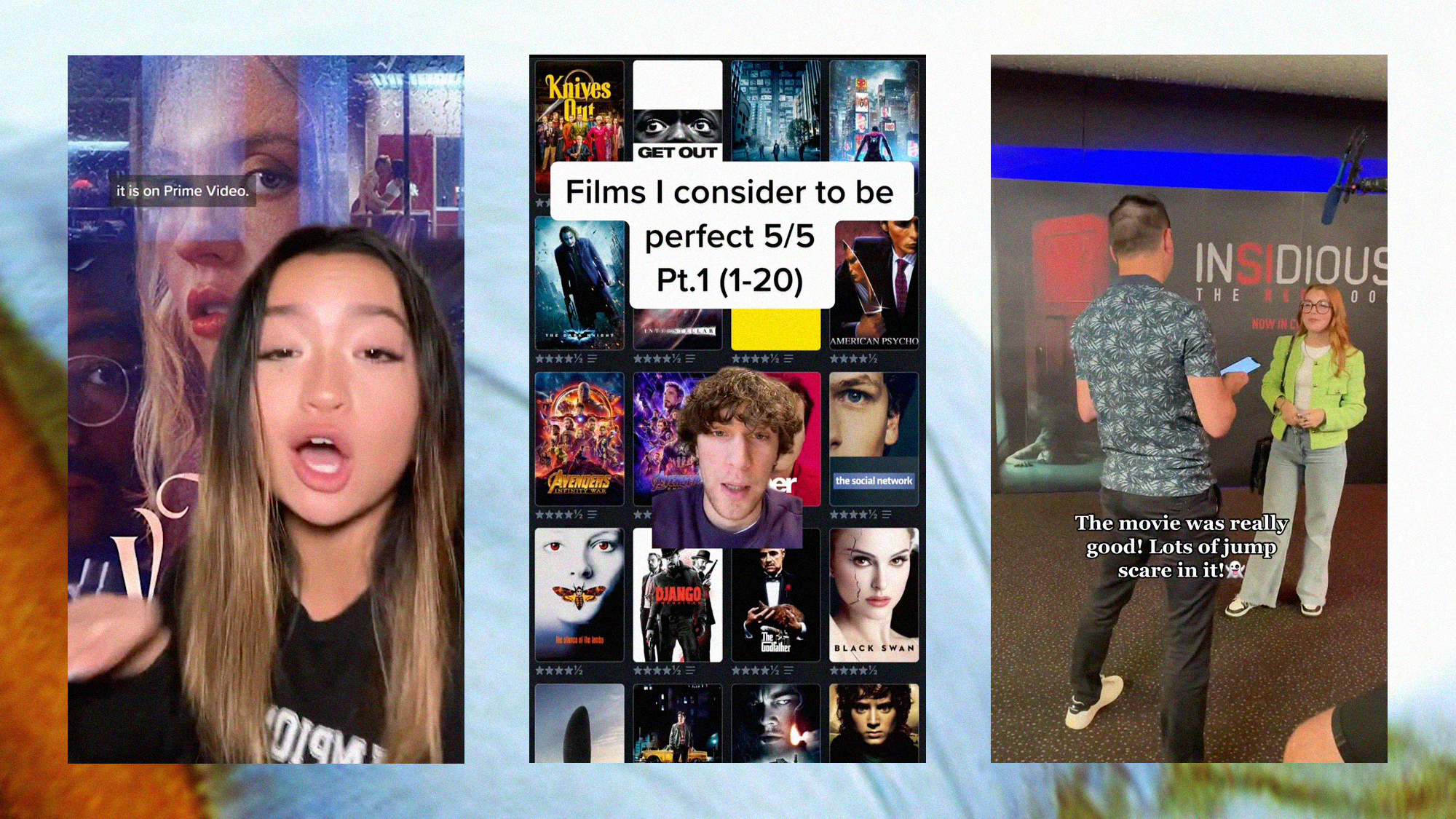

That’s the issue raised by MovieTok, the subsect of movie fans on TikTok who, as a recent story in The New York Times reported, don’t see themselves as critics. They post videos recommending new releases, rank genre movies and franchises, and, in some cases, conduct pre-vetted junket interviews with film stars. They are the new generation who claim to hold opinions more in keeping with “actual” moviegoers (The Meg 2: The Trench has an audience rating on Rotten Tomatoes of 72%), while critics are old news. Naturally, film critics aren’t happy about that.

The historical framing of the film critic from the outside is one of a snob: someone who considers their tastes informed and superior, who looks down on those interested in franchise filmmaking and popcorn movies. (A stance I’ve found to be mostly untrue.) MovieTok claims to operate on a different wavelength – pure vibes, an ‘if-I-like-it-I-like-it’ mentality. They accept money from studios to promote projects they purport to be excited about. As a result, the MovieTok crowd are supposedly sullying the profession, and getting richer than critics in the process. Naysayers will claim this crowd – who generally skew young – are uneducated. As film writer Jordan Ruimy writes, “I can’t tell you how many [new] film critics I’ve met who haven’t seen Vertigo and Citizen Kane.”

We’ve seen supposed changing of the guard before: historically with fashion magazines and more recently with “real” musicians, who have lamented the rapid TikTok ascent of new popstars who have, you could claim, just got lucky, snagging recording contracts. It often feels like a glamourisation of the graft. I get it. To have spent years in your industry, working for peanuts, only to see a young person earn hundreds of thousands of followers and get public recognition – as well as a healthy pay packet – for their lukewarm opinions, doing a similar job to you, must be frustrating. With their readymade platforms they have what many struggling modern film critics crave.

An ‘us versus them’ mentality creates villains out of young people being lured towards the opportunity to work in an industry that’s exclusionary and often pays terribly. What’s more, these MovieTokkers aren’t walking into the industry and securing a lucrative partnership deal with Disney. For the most part, they’ll be performing the on-camera version of SEO content for a half-attentive, smooth-brained audience for a while before the deals and creator fund cheques pile in. But if they’re not calling themselves critics – if they’re not claiming to be impartial – then it shouldn’t be a problem.

Good criticism doesn’t stem from preferential access or treatment. We are in a hot take economy where being early to something is somehow conflated with being correct. (At film festivals, journalists too tend to scramble out of cinemas to tweet their take, often offering overly gratuitous praise that tempers as time passes.) But some of the best criticism these days is published days, if not weeks, after release. Slow journalism makes, for the most part, better writers. Perhaps, instead of venerating MovieTok for getting the plush seats at early screenings in exchange for glowing praise, we should be pivoting our own journalism away from the hot take landscape and towards the kind of ‘takes’ that require time, reflection and proper attention? Social media, at least, doesn’t possess the patience to wait for that.

The film critic is important and, in certain circumstances, as valued by the public as ever. Independent cinema lives and dies depending on their opinion. But the column inches in broadsheet newspapers dedicated to popcorn movies matter little to the crowds who see films based on the trailers, who see going to the cinema as a passive activity tacked on to a catch-up with their mates, as opposed to an active involvement in an art form. The two kinds of movie fans can coexist.

The likelihood of film critics being shut out of a press screening of, say, the forthcoming Sofia Coppola film Priscilla or David Fincher’s The Killer is impossible to fathom because good filmmakers respect those who write impartially about their craft. Similarly, the compromise Greta Gerwig made when signing on to write and direct Barbie was the interference of a media conglomerate who could make decisions that override her own. Do we think Greta herself had a say in who could see Barbie and when? Would she, given the choice, implement the same tactic on a film she had more say in the marketing of? I don’t know. She comes across as the kind of filmmaker who understands the importance of both supportive and dissenting voices surrounding her work, as someone who – like many – learns from these informed opinions.

The influencer is, by nature, influential, but a good critic is an artist unto themself: venerated, wise, trusted. In three decades’ time, 2050’s equivalent of Quentin Tarantino (who is expected to start production on his film, The Movie Critic, after the SAG-AFTRA strike ends) won’t be making a biopic of a teenager telling a blue light-addicted audience on their phones that Insidious: The Red Door is genuinely terrifying, and will keep them up at night.

MovieTok is a moneymaker – an unstoppable feat of modern media that movie studios are understandably grateful for – but it’s an artless endeavour with a short term cultural legacy. Critics shouldn’t fear MovieTok or feel angry about its existence. If you never have to attend an early screening of the inevitable next instalment in The Meg franchise filled with teenagers brandishing ring lights, maybe that’s a good thing.