As thousands protested in London in the wake of Sarah Everard’s death, exactly one year after Breonna Taylor was killed by police officers in her own home, the conversation online has turned to the constant threat of violence by men against women. This occurs during what the UN describes as “the shadow pandemic”, noting that, since the outbreak of Covid-19, all types of violence against women — especially domestic violence — have intensified. And, in regards to the recent rise in anti-Asian violence and hate crimes in the US, new data shows that a disproportionate number of these attacks have been directed at women. This research was released by Stop AAPI Hate on Tuesday, the day six Asian women were killed by a white terrorist in Atlanta.

Over the last week, social media users have shared safety tips for women walking home at night and explainers on how to use the emergency services on your phone. Partly, because the murder of Breonna and Sarah at the hands of police has made one thing abundantly clear: increasing policing isn’t the answer when advocating for women’s safety.

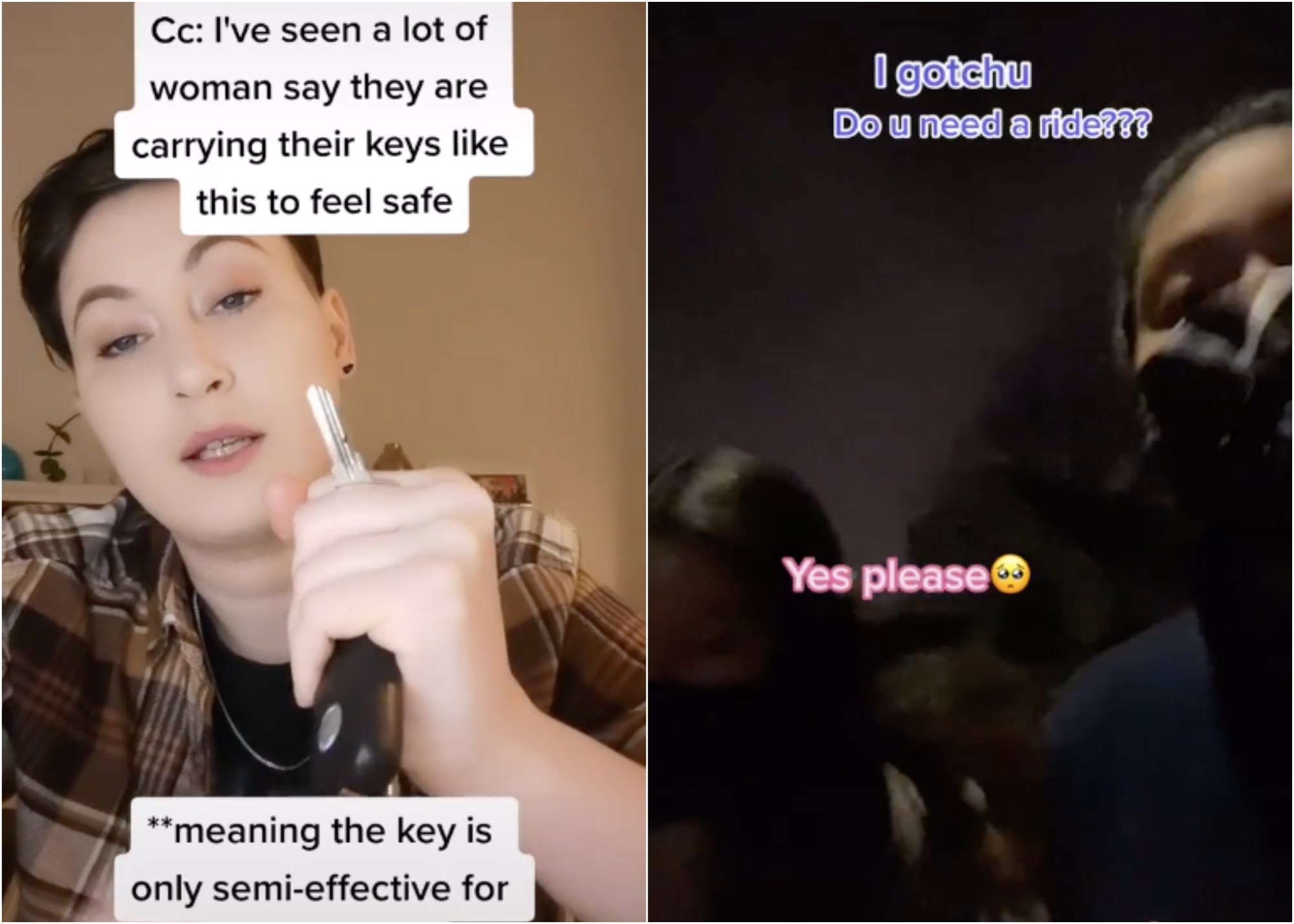

As a result, some women have started using TikTok to promote community action when it comes to unsafe situations. Earlier this month, one user documented herself helping another woman she noticed looking uncomfortable on the street. Brenisen Wheeler, Education and Outreach Coordinator at Women’s Advocates, says the video is an important example of bystander intervention. “The components of trauma-informed responses are trust, collaboration and empowerment,” she tells i-D. “In the video we see a person accessing their own safety, approaching the other girl in a way that seems really supportive, offering collaboration and choice by asking the victim if ‘we know him,’ then choice empowerment by offering a ride.” Brenisen says this allows a victim to take agency for what their safety needs are and that videos like this one might give others considering bystander intervention guidance on how to help someone in need.

It’s also not the first time TikTok has been used to showcase incidents of stalking or harassment. Its “what I was wearing” trend, where users show the outfits they were wearing when they were assaulted takes a stand against victim-blaming. Then there’s the abundance of self-defence videos shared on the app. Last year, another viral video documented a woman being followed by a car. The creator behind the video, Lizzy Wong, says she initially filmed it to show to the police but decided to post it on the app because it was something she’d never seen before. “I posted a part two, and everyone was making fun of me because I sounded like I was crying when I talked to the police,” she says. “I don’t think they understand how scary a situation like that was.”

The increased awareness and dialogue from these social media discussions, Brenisen says, has the potential to motivate a group to talk about plans for navigating safety. “On a general level, this is something that is not always in the public discourse, or something that people feel really uncomfortable talking about,” she explains. Brenisen says that the best way men can respond, both effectively and compassionately, is by centring and believing women. This is one thing that’s completely absent from the “not all men” argument.

Mendy Perdew, who’s been creating “safety call” videos on TikTok for women to use in unsafe situations, was inspired to create helpful content in the fight against gender-based violence after she missed a call from a friend, who was walking home alone one night. She created her first video for that same friend, and her daughter told her to upload it to TikTok, where it went viral under the hashtag “safety call.” On the recorded calls Mendy shares, she often gives listeners the impression that she is expecting the caller to return soon or knows their exact location. The fake calls aim to scare off anyone nearby.

The response, she says, has been overwhelmingly positive. “One lady was being followed and actually dueted my video while she was walking down the street. When she held the phone up, he ducked and she got to safety.” Mendy has since taken specific safety call requests from people across the world and has been working with other creators to translate the videos into different voices, accents and languages.

Nancy Ross, an Assistant Professor at Dalhousie University, who researches gendered violence, thinks the informative and helpful conversations taking place on social media could “further the goals of the #MeToo movement by encouraging a more collective response.” “What you’re seeing in some of these TikTok videos is a disruption of individualism and a demonstration of collective concern,” she says.

Nancy believes that women sharing their experiences is fuelling a more coordinated movement. “Historically, and still today, gender-based violence and sexual assault have been characterised by silence and stigma,” she says. While Nancy sees some of the ongoing conversations as finally recognising the scope of the issue — especially the intersectional nature of gender-based violence — she thinks male creators making informative TikTok videos is only “one small part” of cultural change that’s needed at a much larger scale. After all, patriarchal cultural and social norms are highly influential in shaping violent individual behaviour.

Creators and experts alike aren’t suggesting that TikTok or any social media platform can solve large societal issues, like the epidemic of violence against women, but the messages of collectivism and community outreach are hopeful in spite of other sexist, racist and ableist content on the app. The videos also potentially indicate a more action-based shift in how we combat violence at large, something that’s desperately needed considering the current surge in violence against women.

Note: If you are in danger and in need of help, consider calling the Women’s Advocates 24/7 Crisis Resource Line at 651-227-8284, or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.