There is a gray sweatshirt Tilda Swinton shared with Derek Jarman. One of them would wear it, wash it, and then leave it in the linen cupboard at Jarman’s Prospect Cottage, passing it on for the other to repeat the ritual. On the day Jarman died of AIDS-related complications in 1994, it was Swinton’s turn to wear it—“I just happened to have it with me when he left,” she writes—but she never did again.

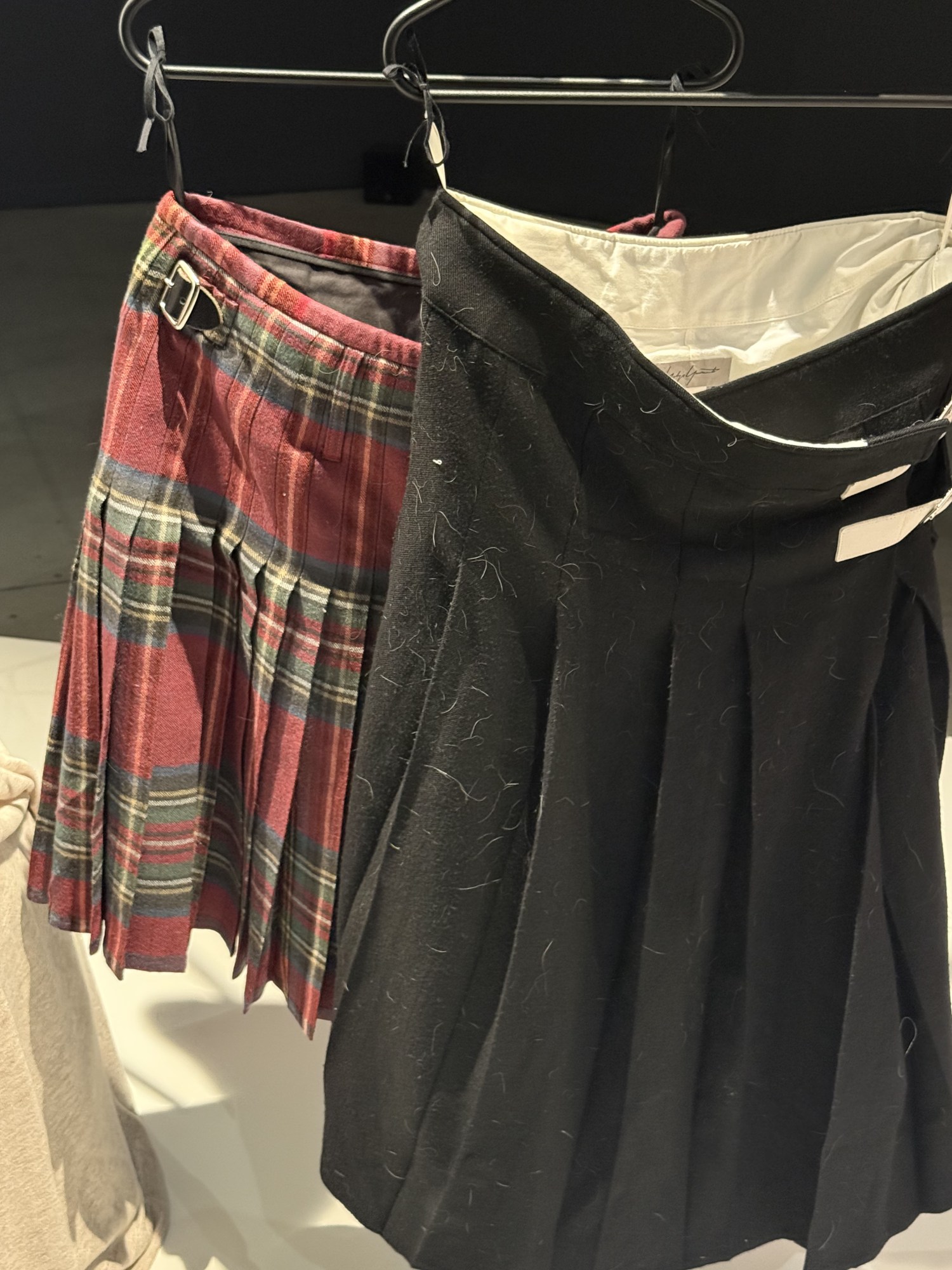

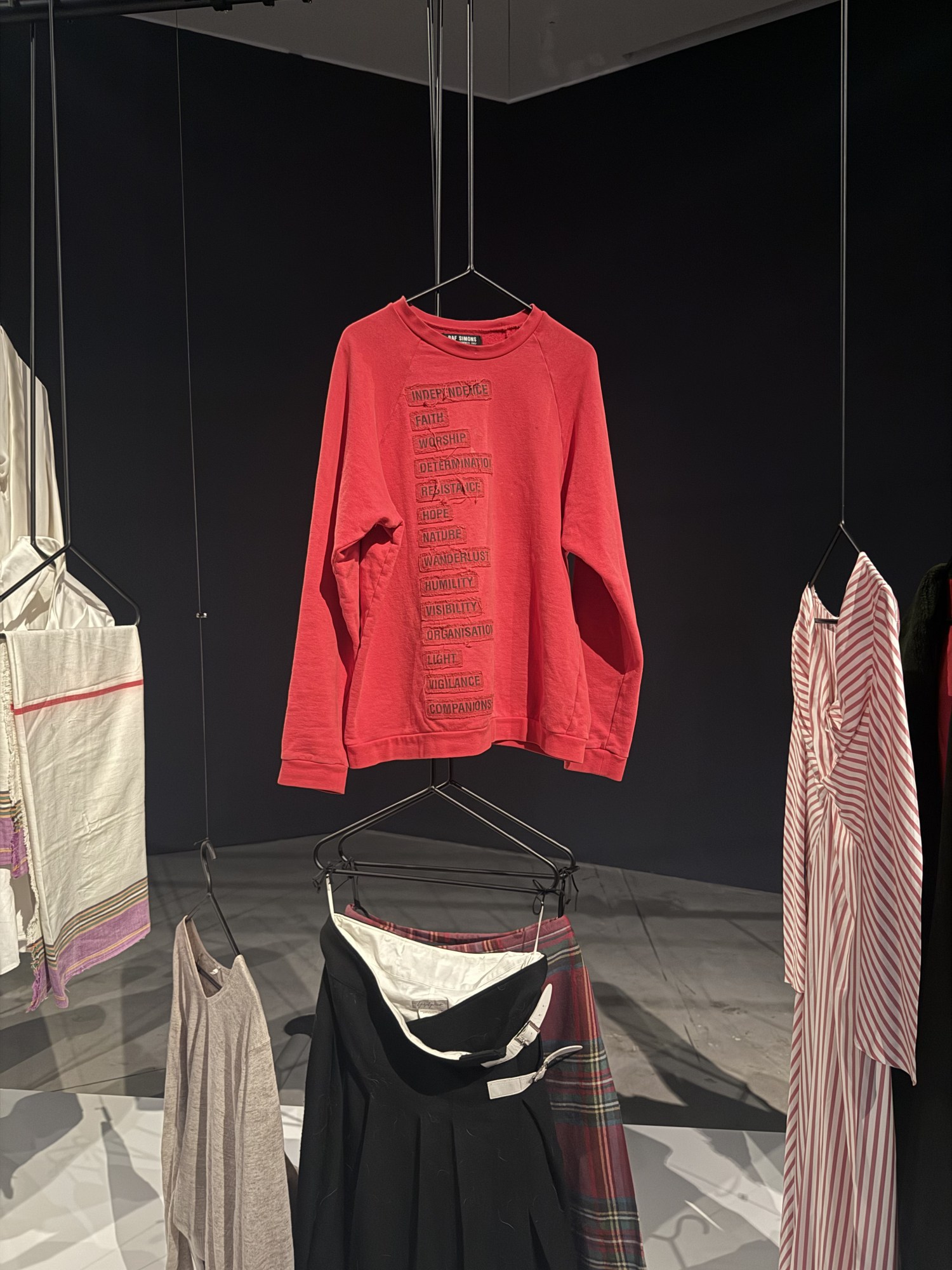

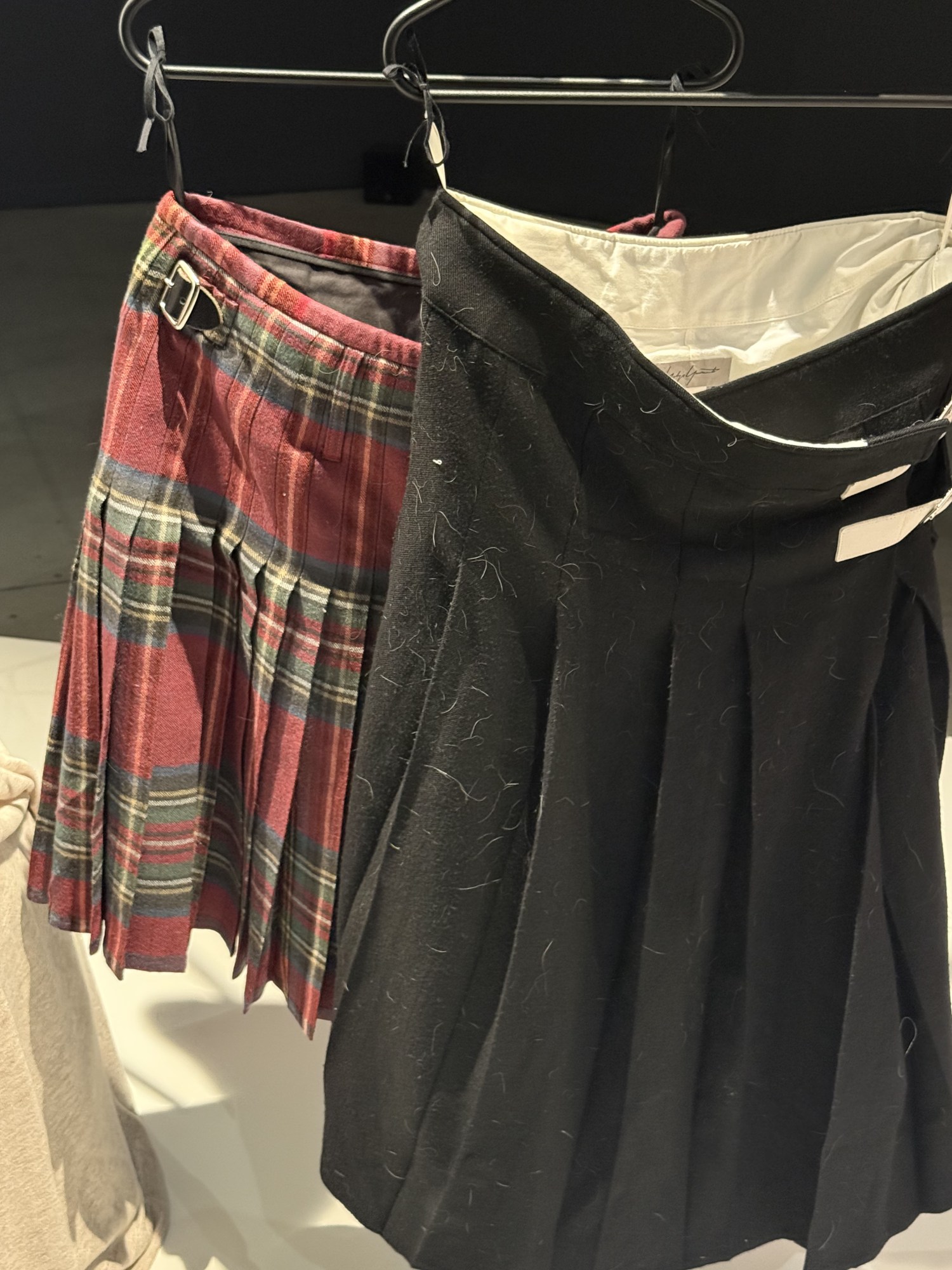

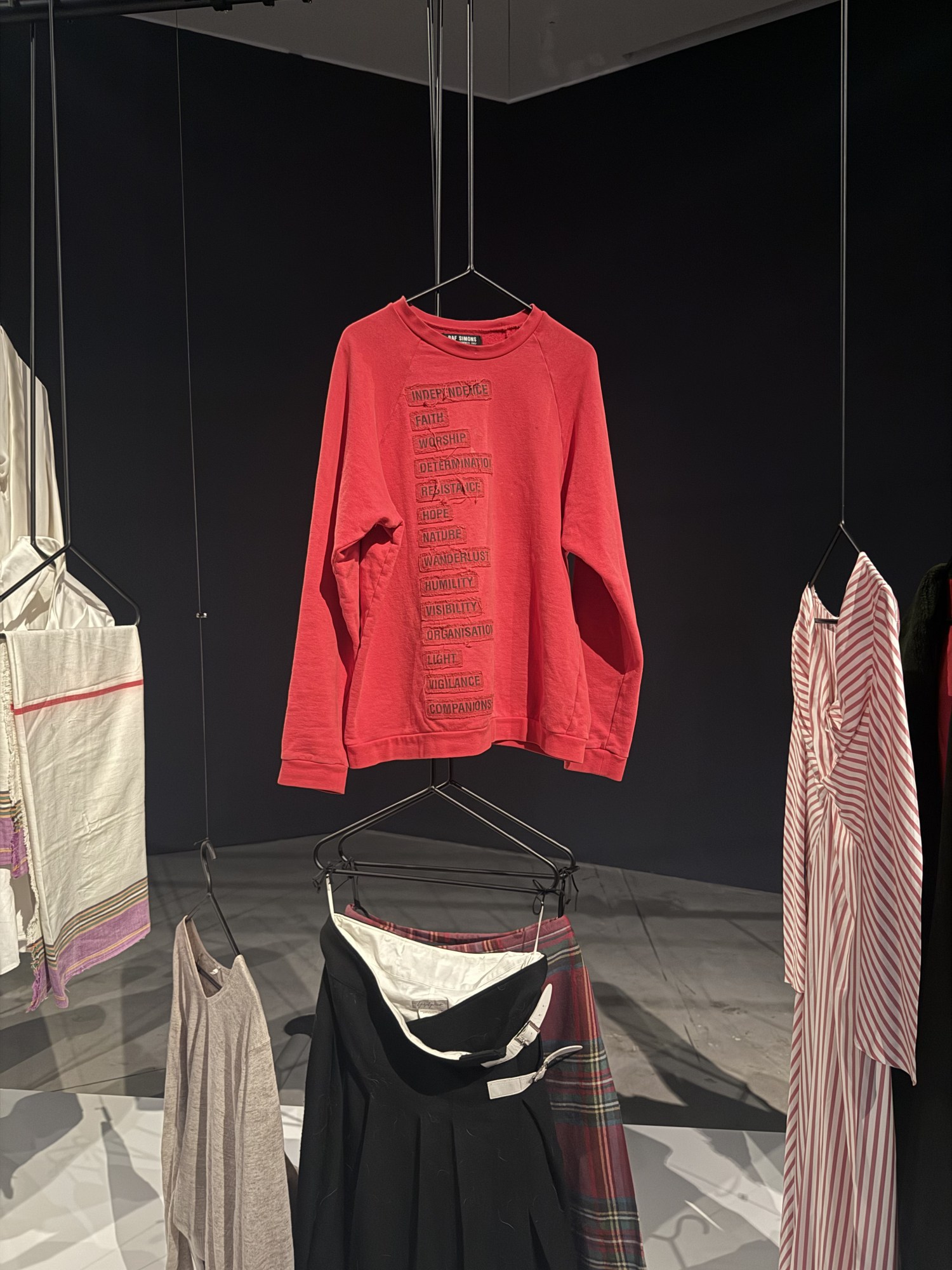

She unpacks it ceremoniously, like a precious artifact, and holds it up to her chest like a child being comforted. This is part of A Biographical Wardrobe, a performance directed by Oliver Saillard, who converses with her during it. The piece forms one element of an expansive exhibition about Swinton’s life and collaborators at Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum. If you walk through, anytime from now until next February, you’ll see the objects of Swinton’s fashion history—including her own family’s treasured pieces dating back centuries—hung straight, like books in a library, as if they’re asking to be pulled down and read.

That sense of discovery, a newness to something that already exists, runs through the exhibition, titled Ongoing. Over the past year, Swinton has immersed herself in its curation, partly because so little of it involved nostalgia. Instead, Ongoing celebrates the “fellowships” of her artistic life—her work with the likes of Luca Guadagnino, Pedro Almodóvar, Joanna Hogg, Tim Walker, and others—and builds new art from those relationships.

She made a short film with Guadagnino running ahead of him through an Italian field, wearing the jumper she wore at their first meeting. With Memoria director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, she created Phantoms, a dreamlike portrait of her home in Nairn, Scotland. With Hogg, she recreated her London apartment from the ’80s and ’90s—Flat 19—which visitors can walk through, hearing recollections of her time there behind ajar doors. The show even includes unseen work from Jarman, discovered and rendered on large screens as a luminous tribute to their artistic and personal kinship.

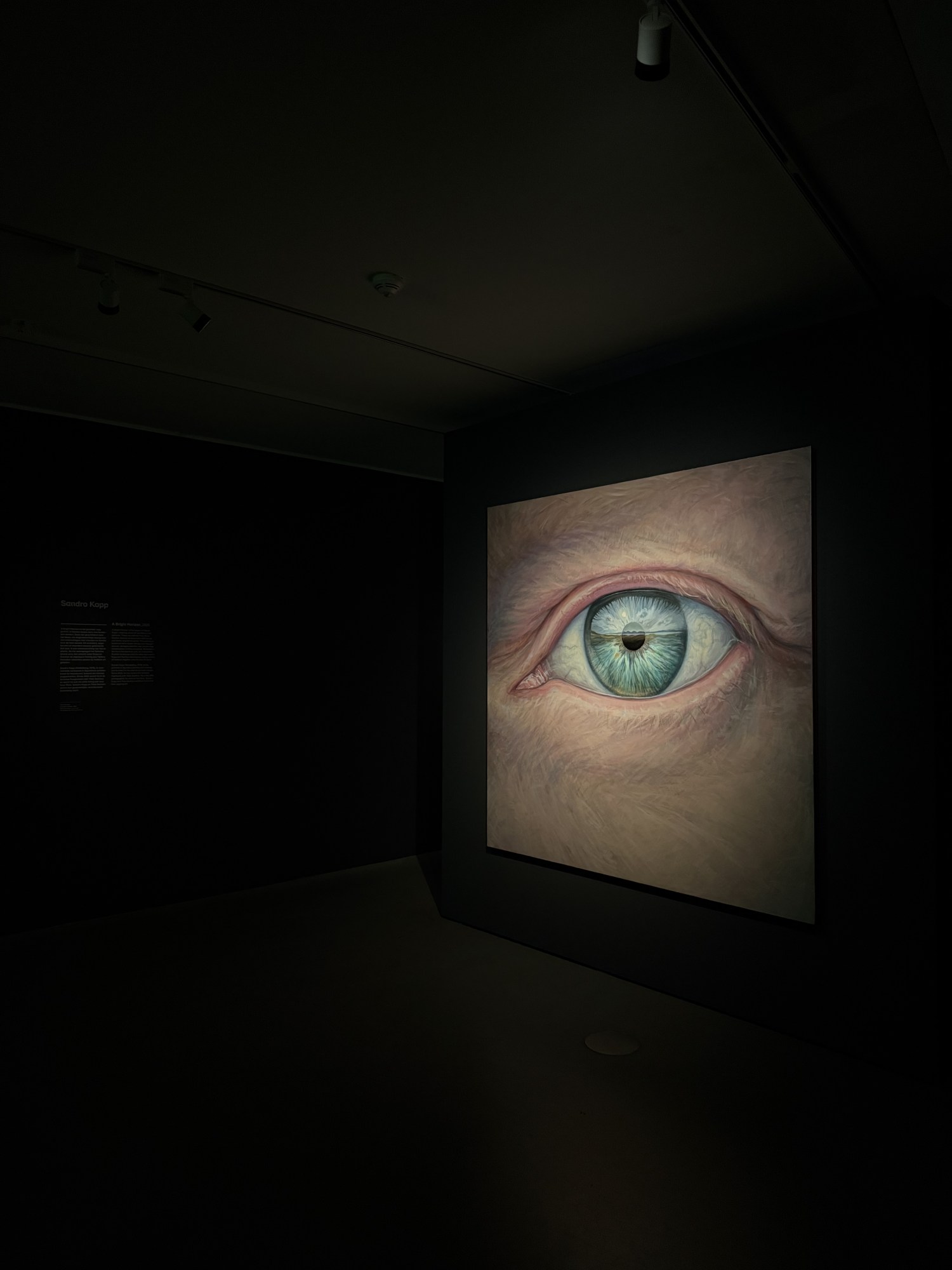

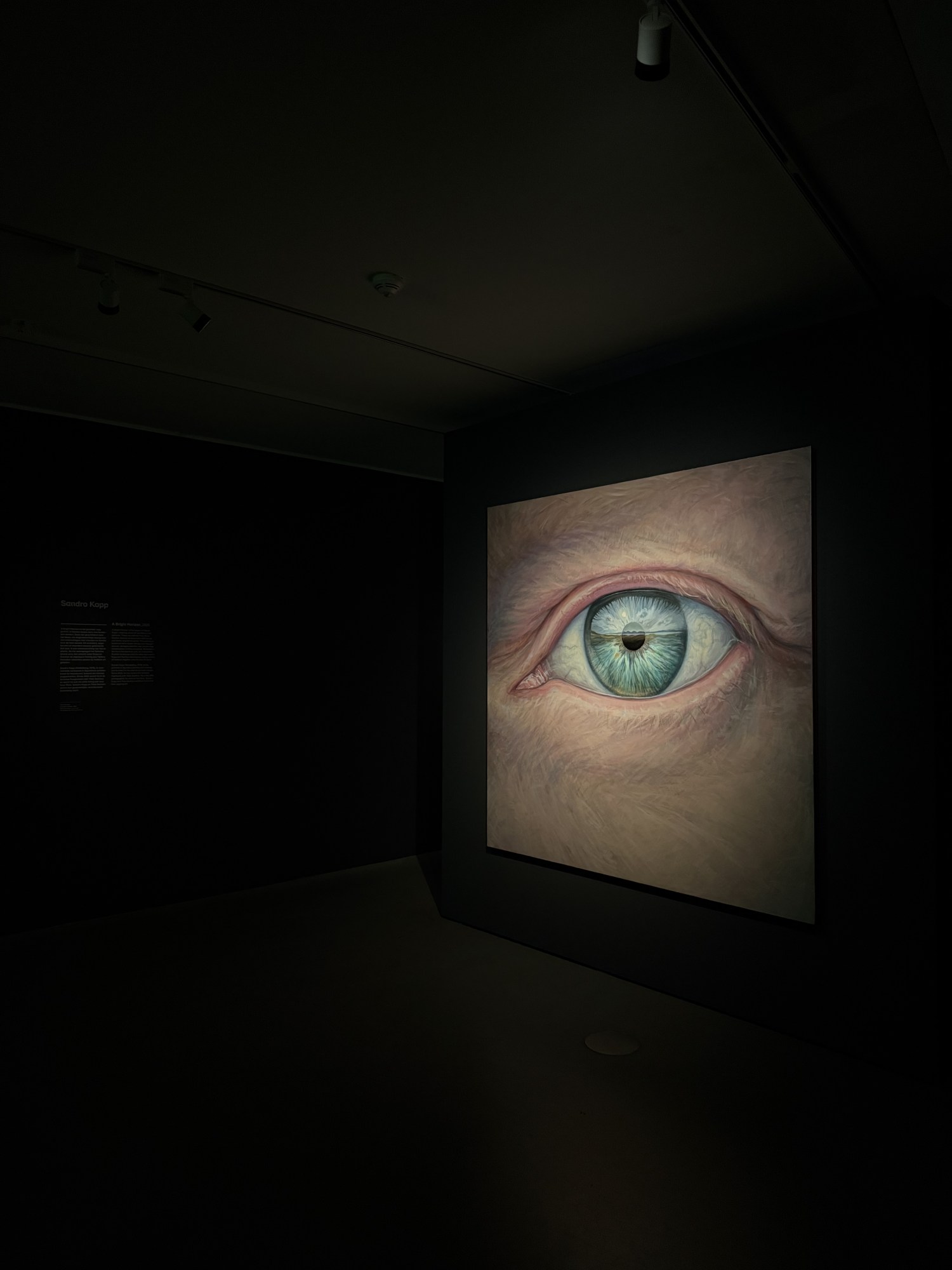

In the final section, visitors confront a towering portrait of Swinton’s eye gazing out to her favorite view—the Scottish isles of Jura and Islay. When I saw it, Sandro Kopp, Swinton’s partner, sidled up next to me. He had painted it. “Tilda doesn’t call it a retrospective,” he says. “It’s about perspectives instead.”

The next day, following another dress rehearsal, I meet Swinton at the museum. Serene, striking, and easygoing, even stopping for selfies with fans on a Pokémon Go mission mid-photoshoot. (“Keep Pokémon Go-ing!” she shouts back as we scurry off.) Over coffee—which she admitted might be only her second cup this year—we spoke about grief, the joy of creating, and where she might go next.

Douglas Greenwood: I wanted to start with what Sandro said yesterday, about this being not a retrospective, but an exhibition about perspective.

Tilda Swinton: It’s a series of perspectives, really. When [the museum] first asked me years ago if I would be interested in doing a show, I was very quick to say no, but that was a failure of imagination on my part. I couldn’t really foresee a show based on my work that wasn’t just about old stuff. I was a bit in the woods at that time. I couldn’t see the shape of it. And then, more recently, I started to think: What if there was a show that was based on my fellowships? Then I could imagine a through line. And what’s emerged in the last couple of weeks is how related all the works are. A lot of them are friends anyway, but not all of them, and still their works echo each other. It’s become a very cohesive group show.

The show looks back with the intention of making new art from history: like Jim Jarmusch’s piece that resplices your work from The Dead Don’t Die into something original, and the performance aspect around “A Biographical Wardrobe.” How often do you encounter art that feels new?

The older I get, my attachment to the materiality of art is partial. I’m much more interested these days in the spirit and the gesture—even with something as material as painting. Recently, we were looking at Van Gogh paintings, as you do in Amsterdam. You may not know anything about his life, but you could feel the energy of the way he lived his life from the way in which he uses paint and perspective. As I say in my show, it’s the tree I’m interested in. The leaves—the works—are evidence of a life. But it’s the life that really interests me.

You talk about spirit, and I wanted to ask about the presence of so many of your gay collaborators—Derek Jarman, Luca Guadagnino, Pedro Almodóvar. Did you ever identify a shared spirit or language with gay male artists?

It’s very true, and at the same time that shared language also exists with artists I work with who aren’t either male or gay. The world I entered when I started living alongside Derek was a queer world. That was exactly what I was looking for. It was completely inclusive, and democratic, fun, and without, at that point, a sense of judgment. We both know there are less kind and less inclusive corners of the gay playground, but I’ve always avoided them.

It’s not transgressive to say that we all make a step in our lives. I made one when I left my family’s world. I became politically active, and I really did want to identify myself in a completely different way than the way I’d been identified by my family. I’m not saying it’s the same [as others’ experiences], but it was painful. I suggest that everyone comes up against that kind of precipice, and some people find it too difficult: “I’m just going to put on the green dress, and behave like my mother wanted.” When I met Derek and lived among my friends at that time—with the exception of a few who are no longer here—it was the start of an ongoing, everlasting kinship.

I cried when you spoke about Derek and the jumper you shared during the performance last night. It made me think about grief, and the objects we hold on to in order to remember people. I lost my mother when I was a child—

Do you have things of hers?

I inherited her watch. I remember wearing it to school the day after my dad gave it to me and getting a scratch on the face, and feeling annoyed at myself that I’d damaged it. Your performance, and the sweater, reminded me of how important it is to honor grief.

I hope people notice that all of these relationships are ongoing. They’re all alive, even my relationship—in many ways, most of all—with Derek. He’s the battery I draw on, and have drawn on now for 40 years. Some people have terrible, wonky batteries that give them weird signals, but he is an everlasting source of nourishment and companionship for me.

Do you feel his spirit around you?

I do. There are a few things I really lose my sense of humor about—like the fact that my children never met him, or that Sandro never met him. I have a sort of deal with mortality. I’m working out a way of navigating it. But there are a few things that really annoy me, like when people don’t know each other. My children never knew my grandmother, and I can hardly believe it. But if you’re the lucky one who did know these people, you can draw on them forever.

Exactly. You have these memories of him, and his work, to share with them.

And the memory is like your mother’s watch. I would suggest that the scratch on the watch is also precious. It’s a memory of you at eight or nine years old, just as much as it’s a memory of your mother wearing it, so it’s part of its history. You’ve contributed to it. A memory isn’t fixed. It’s a constant parlaying of energy. That’s how I feel about my departed. They’re still sort of chatting away.

Your youth is also a ghost. When I walk around this show, I see myself in those fragments. One of the things I’m most proud of is producing new work from Derek Jarman—those fragments at the beginning that no one had seen before. Me in front of the camera in the first months of my life as a practicing artist, figuring it out in a raw and molten way. And then going into the flat that I built with Joanna and feeling the development of that person. They’re ghosts, very distinct from me.

You’ve called working on this exhibition a watershed moment in your career as a performer. You’re making your next film with Apichatpong in February. Do you think that experience will feel different?

The Joey [Apichatpong’s nickname] piece is something we’ve been talking about for a long time. So in a way, the shooting will just complete a process that we’ve already begun. It doesn’t feel like something new.

Is there something that only performing scratches? That you wouldn’t get if you gave it up?

For many years, performing scratched the writer who wasn’t writing. Now that I’m writing, I don’t know where performance sits. This is a watershed in the sense that I’m going to have to see how I feel afterward. But I’ve enjoyed the work of curation so much. I’m not saying I’d necessarily become a curator, but it’s been satisfying on such a massive level. And I’ve been involved in making a book—the exhibition’s catalog—which has always been a dream.

I’ve got so many new dishes on my table. I wonder what kind of performance opportunity it would take to draw me back. Let’s see what the universe throws up. But I’m making my own work now, and I’m enjoying it.

‘Tilda Swinton: Ongoing’ runs at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam until February 8 2026. In addition to the exhibition, there will be a series of conversations and screenings. More information can be found here.