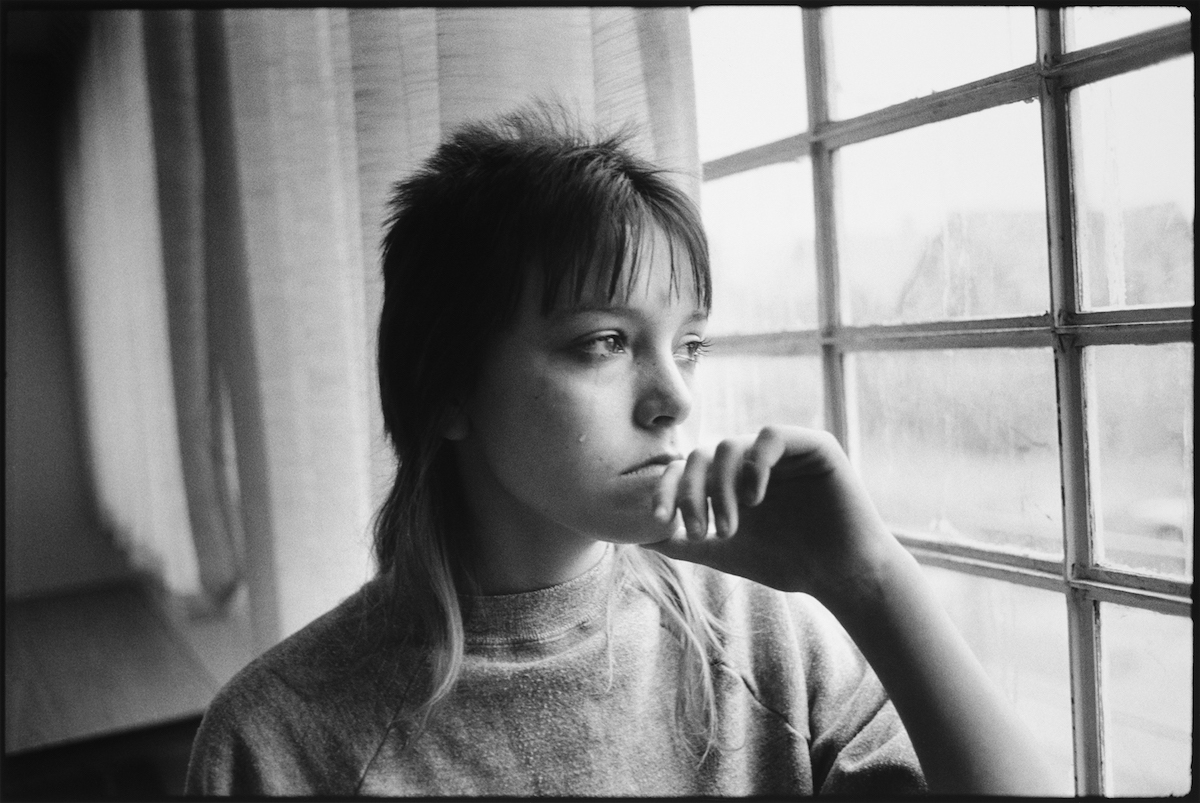

“Everyone loves that picture,” says Mary Ellen Mark in a scene from Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell. She’s looking at the iconic photo she took of Blackwell 30 years ago, as a willowy 13-year-old prostitute wearing a little black dress, black gloves, pillbox hat and veil, and a stony expression. Blackwell, aka Tiny, is now dangerously overweight, a mother of ten children, and no less captivating than she was when she became the star of Mark and Martin Bell’s 1984 documentary Streetwise: a haunting, intimate portrait of Seattle street kids that started as a photo series for Life magazine. The Academy Award-nominated documentary followed the lives of eight teenagers — including Tiny, Rat, Shadow, LeMar, Patrice, and Wheelchair Mike — surviving on the streets of a city that had ironically just been named one of the best places to live in America. 32 years after the original documentary — and a year after the death of his extraordinary wife — Bell has turned the footage they shot together in the intermediate decades into an equally powerful story of trauma and, ultimately, resilience.

Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell will screen at BAMcinématek film festival this Saturday along with the original Streetwise documentary. Comprised entirely of unseen footage of Blackwell and her incredibly charismatic children, the new film is a story that feels more relevant than ever, because the same factors that pushed its protagonist into a spiral of self-destruction continue to exist today. Ahead of the screening, i-D spoke to Bell about keeping in touch with the Streetwise gang, meeting Tiny’s children, and what he hopes to achieve with his new film.

What is your memory of seeing Tiny for the first time?

I remember Mary Ellen’s excitement when she called me in London the day she first met Tiny. It was 1983 and Mary Ellen was on assignment for Life magazine photographing a story on teenagers living out on the streets of downtown Seattle. Mary Ellen and I first met in 1980 and had been looking for a project to work on together. In the call that day she told me she had been working late at night in the parking lot of the Monastery nightclub in downtown Seattle when a cab pulled up and out stepped a 13-year-old girl she knew immediately was a “star.” It was Erin Blackwell — her street name was Tiny. Mary Ellen then said, “this could be our first project together.” Little did we know then, it was one that would span 32 years. When I first met Tiny, I was struck by how beautiful she was. She was open, honest, and full of life. I had never met anyone like her who was so completely at ease in front of a camera.

How did you earn the trust of the kids?

Mary Ellen was working with Cheryl McCall, the reporter on the Life story. As their work progressed they soon met many of the kids hanging out between 1st and 2nd on Pike Street. Among them were Patti, Munchkin, Lou Lou, Shadow, Patrice, Wheelchair Mike, and of course Rat and Tiny. When we returned to Seattle to make the film later that year, it was Lou Lou, the leader on the street, who told the kids to “let these old folks do their stuff — they’re here to help.” The first day we started filming in Seattle, we ended up at the Dismas Center, a place where kids hung out. I had focused on one young teenage girl and had shot about eight minutes of film with her when she turned to me and said, “I don’t want to be in your film.” I opened the film magazine and gave her the exposed film. All the kids in the room saw this. At that moment they all knew we were not there to steal anything.

What went through your minds as you watched the cycle of drugs and misbehavior continue with Tiny’s own children?

It’s devastating. But, I believe Tiny was a victim, not the cause. She didn’t start the cycle. She was born into a life she had little control over and boldly made a change by leaving home. She was 13 years old. When you’re caught in it, it’s very hard to see your way out. On Thanksgiving 2015 I brought the almost completed film back to Seattle to show Erin and get her approval. When the film finished she sat in silence for several moments, and then said “Oh Martin — it’s a circle.” I say we have to find a way to break the circle for all the Tinys and their children.

Even though she didn’t manage to break the cycle, she is still something of a success story. Her life could have turned out very differently.

Yes. There’s no question about it. People stand in judgement, but she actually did hold it all together. She survived. When Mary Ellen and I finished shooting Streetwise, we offered Tiny the opportunity to come and live with us in New York. We had one condition — she had to go to school. She said, “I ain’t going to no school,” and she turned us down. Surviving the abuse and degradation of street life for almost 17 years is something few could endure. But she did it, and held her growing family together as best as she could.

So many disenfranchised kids are plagued by so many of the same problems today, which makes even the original documentary feel so relevant. What do you hope to achieve with this new film?

It hasn’t really changed that much. Erin’s story overlaps with so many disenfranchised Americans’ stories — poverty, addiction, lack of education, fractured family structure, etc. I believe the relevance of Tiny’s story today is for it to start a conversation that leads to action. This endeavor’s sole purpose would be to find the key that breaks the “circle” so we no longer have disenfranchised individuals or families. Our society would be richer and more productive for it.

Tell me about taking Tiny to the 1984 Academy Awards.

Oh my God, there was a fist fight between Tiny and [her friend] Kim. It was amazing. Incredible. That was a serious fight. It just came out of the blue. They were hitting each other really hard. We had to bring hair and makeup people in to patch up the wounds. We tried to get Rat to come down, but he was in jail at the time, and he would have had to come with a prison guard. That was a very expensive flight at the time. He would have been handcuffed, I guess — not the normal kind of Academy Awards scene.

Are you still in touch with any other kids from the original Streetwise series?

The day after Christmas 2015, Julia [Bezgin], Hollis [Meminger] (who both worked on this film), and I went out to Sacramento to make a film with Rat. Mary Ellen and I had kept in touch with him since 1983. I suddenly decided after we finished this film that I would go back and make a film with him. He was such a significant part of the first film — their relationship is such a big thing. I was curious to see what he had made of his life, and he’s put it together, which is amazing. The Rat film will be finished by the end of this month. His story is an extraordinary one of survival. Mary Ellen and I also filmed a number of the kids who had survived when we were making the new film: Munchkin, Shadow, Patrice, and Wheelchair Mike. I hope that I’ll be able to work on a series of small follow-up films in the coming months. Some of them have also put their lives together. One of them, Justin Reed Early, even published a book called Street Child.

Do you have any other projects coming up?

Yes. Mary Ellen photographed and I filmed in the streets of New York over the years. What I intend to do over the coming years is to put together a film using her still photographs and the footage I made. I’m also working on a theatrical film with John Irving, the novelist. It’s a project related to his current book Avenue of Mysteries. Mary Ellen and I started working on the project in 1989, and we’ve almost got it together. It was set in India at one point, but now the film is set in Mexico.

“Streetwise” (1984) and “Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell” (2016) screen at 2pm on June 25, 2016 at BAM, followed by a Q+A with Martin Bell.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

All photos © Mary Ellen Mark courtesy of Falkland Road Inc