Preparing for a month-long job in Ukraine this summer, photographer Carl van der Linde discovered the Saber-Tooth School of Combat Hopak whilst doing a little online research. It’s a centre teaching the Cossack martial art that marries traditional Ukrainian fist fighting, folk wrestling and Cossack sabre fencing with Cossack war dances like the Hopak and the Metelytsia. Initially looking for a place to continue his boxing, the school’s distinctive appearance evoked something more in him.

“Boxing is, visually, quite generic,” Carl tells me. “It has a universal look and feel to it, always with a blue corner and a red corner.” Saber-Tooth, however, had something more to it.

Previously in Zanzibar, working on a story about street culture (which he shared with us earlier this year), Carl travelled next to Istanbul before arriving in Lviv in Western Ukraine. “A lot of people associate that part of the world with the Soviet grip, and I could see it – Ukraine obviously suffered in the Soviet era. They had been very rich in culture, but it was all stripped away by the Soviets, so, originally, I wanted to do a piece on the Ukrainian cultural revival.” Realising this would be too broad to quantify into a single story, he decided to focus on a specific area of national identity and approached the school about doing a project.

“There’s no information online – a simple Wikipedia page, one Facebook group and a YouTube video,” he says. Pitching himself as a documentary photographer, Carl waited three weeks before hearing back from Andrij, an ex-military man who now acts as a spokesperson for the school. “I suggested I come to the gym and do a bit of a gonzo where I fight and take some pictures because I was genuinely interested in learning this. On the first day, I went to the gym without my camera, and it was a crazy experience. Those guys are tough as nails.” Returning the next day with his camera, Carl’s initial portraits were lacklustre: the light was too dim, and he didn’t have a flash, while the building’s interior made the pictures generic. “The only thing that made it look different was the outfits.”

Disappointed but not totally disheartened, he remembered a YouTube video he’d found back before he’d arrived at the school, of students running around in the Carpathian Mountains. “It’s visually stunning, a bunch of people who you can’t place in terms of which martial art it is or where they are.” He spoke with Andij about joining one of these excursions, went on to spend four days with the group – a mix of teen boys and older men – at their summer retreat in the woods, ten hours away from Lviv.

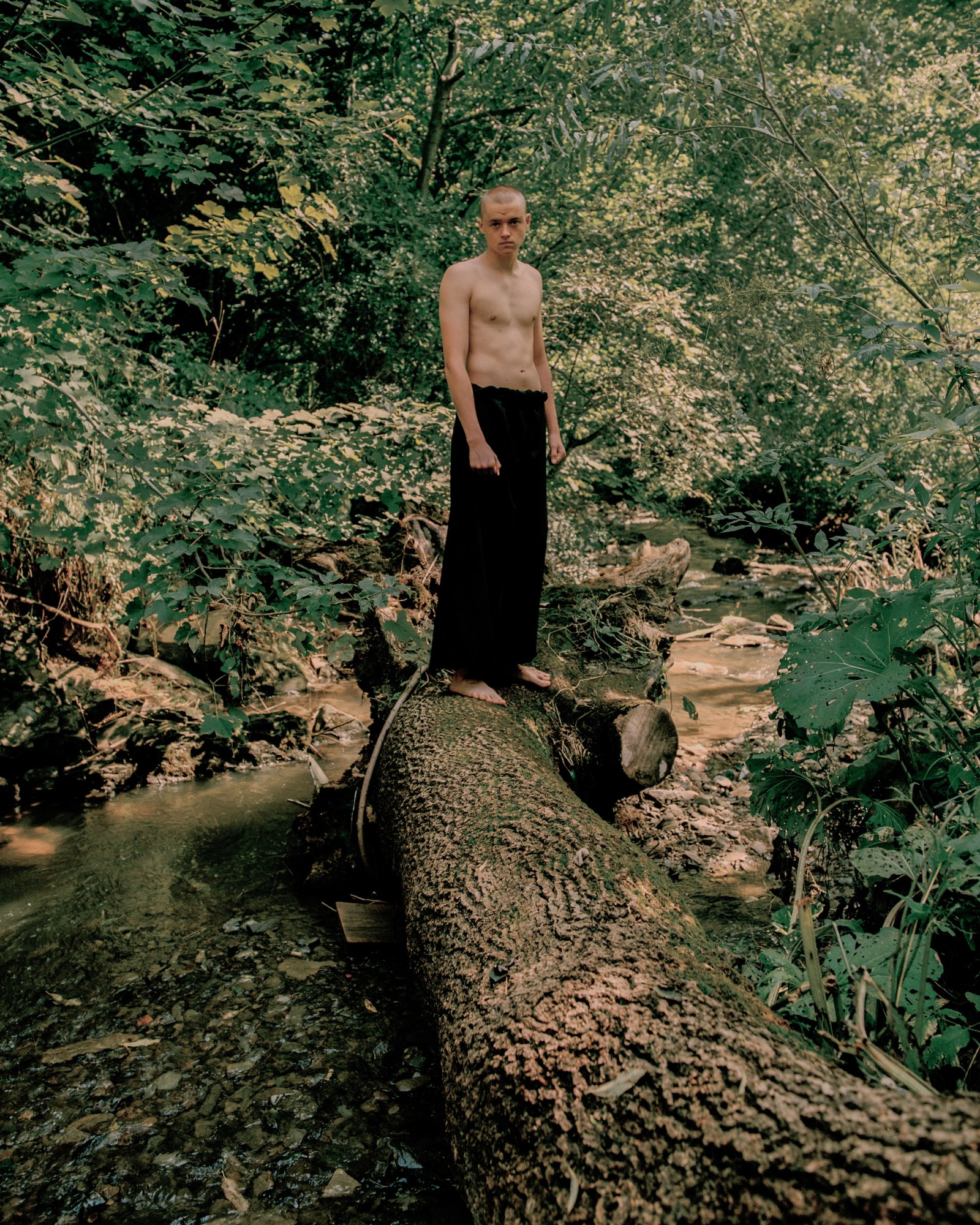

It was awkward at first, Carl explains. “They didn’t understand who and what I was, and they spoke no English. “I was like ‘wow, I really didn’t sign up for this’. And then I remembered I actually did; no one forced me to be there. But they were super welcoming after a while.” Throughout, Carl observed and captured tender moments between the boys as they shaved each others’ heads and tended to big pots in the kitchen. Elsewhere he documented the more formal rituals, as the boys stood for a ceremony and helped one another fasten their sharovary (the black and red uniforms).

The resulting images have a softness and delicateness to them that belies the strength of his subjects. “One day, one of the guys brought a rugby ball and gave them a 10-minute crash course in rugby. They don’t play rugby in Ukraine and obviously had never seen that South Africa are the world champs, so when we played – and I was good – they were instantly like ‘ok, this guy’s cool’. They could relate on that front, sports.”

While ultimately the school is concerned with preserving Ukrainian culture, Carl’s images take an objective approach, leaving the narrative to be shaped by the beholder.

Credits

All images courtesy Carl van der Linde