The place barely attracts any cars any more, and takes up a huge amount of now incomprehensibly valuable land. Most of the building is almost totally unused except, of course, the roof. Since 2008 the top of car park has been home to Bold Tendencies: the annual sculpture show, performance space, and open air cinema, as well as being home to Frank’s Cafe, the Campari bar with the best views in London. Every year tens of thousands of people descend on Peckham, locate the car park, ascend the piss-soaked staircase to the sixth floor and emerge onto the rooftop.

Before the wrecking-balls arrive however, Southwark Council have decided to transform the whole building into a temporary community arts space. They will hand over all six hard, concrete floors of the car park to Pop Community Ltd, the architectural development firm responsible for Pop Brixton, the shipping-container-cum-psuedo-permaculture commercial dystopia. Pop plan on bringing their brand of upwardly mobile fairy-lit fun to South East London in the form of Peckham Levels, a project which will house fifty artist studios, office spaces, shops, performance spaces, cafes and bars. Pop fought off competition for the building, and were awarded the development contract over a number of other projects including Bold Home – a plan devised by the team behind Bold Tendencies and Frank’s Café, and entrepreneur Rohan Silva, of Second Home. But Bold Home would have forgone the pop-up, Instagram-friendly sensibility of so many of London’s new cultural ventures, and instead, installed up to 800 affordable artist’s studios in the car park. By plumping for Pop over Bold Home, Southwark Council have essentially turned down the chance to focus on nurturing the next generation of creative people in London. Instead, the worry is that Peckham will now get a monetised, franchised, shiny imitation of the sort of organic creative community it already has.

The Pop Brixton developers are promising to hold community meetings and public consultations during the planning process, to help ensure that Peckham gets the ‘cultural hub’ it deserves. Unfortunately Pop’s track record with this sort of stuff isn’t exactly great. Pop Brixton was originally pitched to locals as Grow:Brixton, but once the lease was awarded the team split and the focus moved away from horticulture and towards commercial opportunities. Pop promise that a key aspect of Peckham Levels will be the provision of free outreach and community projects. Cheap studios will be given to local organisations, subsidised by other more expensive ones. As well as studios, office space and workshops, Peckham Levels will boast ‘a performance and multi-purpose event space’, plus retail units for local artists to sell their wares, and food and drink spots for local tradespeople.

This all sounds great, but the problem is, Peckham doesn’t really need any more places for people to come and buy drinks, see some art and have a nice time. The top two floors of the car park already cater for that in the form of Bold Tendencies and Frank’s Café. The neighbouring Copeland Yard and Bussey Building are now full of commercial ventures, galleries, clubs and restaurants. What Peckham needs isn’t more space for entertainment – what it needs is cheap space for work.

Bold Home would have been the largest cluster of creative studios in London. Between six and eight hundred cheap studios (£200 per month all in) in one place, for five years. Imagine the work, the connections, conversations, accidents, parties, chance encounters, meetings, co-operation, exhibitions, arguments, ideas and industry that would have poured out of that factory. Many people question why some artists feel they are so deserving of urban space, and protected as if they were endangered species, and they are right to do so. But Bold Home wouldn’t have just been inhabited by oil-paint splattered toffs. It would have also been a development space for writers, film-makers, designers, architects, illustrators, sculptors, product designers, photographers, tailors, small businesses, musicians and performers. The loss here, isn’t just the cheap space for these creative, enterprising people to work and grow, but the space for them to all be in the same place at the same time.

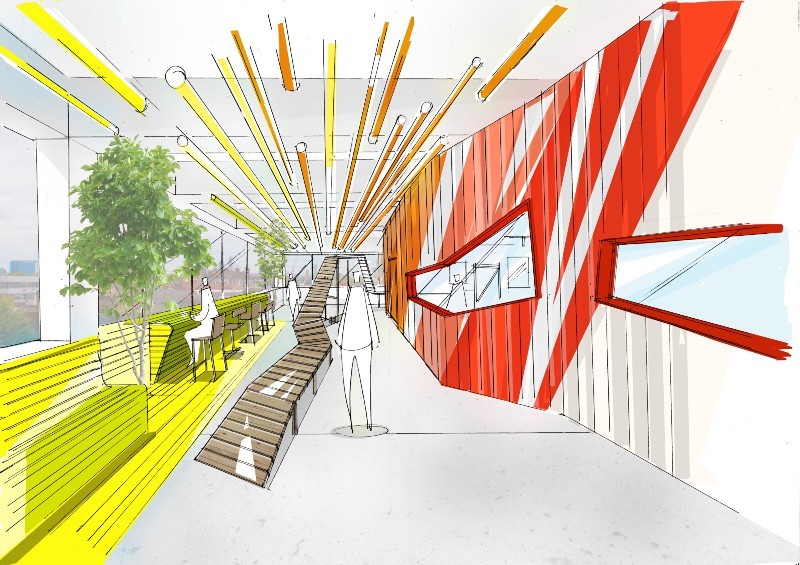

The key difference is affordability. Bold Home would have kept studio rent prices low by keeping infrastructure simple and functional. Rooms, electricity, heating. That’s about it. Turner prize-winning architecture collective Assemble designed a system of modular units for the project, which would have cost about a grand each to put together. Peckham Levels, on the other hand, is a far more public-facing proposition, and so will need to look and feel more like a visitor destination – which means an awful lot of work. The roof of the car park might have the attractive views, but down below, it’s just a car park. It’s cold, hard, drafty, grey and gritty. In order to transform the building into the welcoming, bright cultural hub they are promising, Pop estimate that they are going to have to shell out about £3million. Being a commercial venture, they will then have approximately four years to recoup that significant investment. Studio and commercial rents are likely to be higher, which means prices at retail and food outlets will be too, attracting increasing numbers of wealthy people to an area in which the yawning great chasm between rich and poor has opened up. These retail units will be for resident artists to sell their creations. It’s a nice idea, but problematic, as it requires the studios to be inhabited by artisans who can produce relatively cheap, sellable work. Creating an environment in which to display such items for sale isn’t cheap either – it can’t look like a craft market in a car park.

Then there’s the fact that the clientele who can afford what Pop are offering won’t come unless it’s a slick, polished operation. It’s a vicious cycle of investment and expectation. It means that the people who come to work in Peckham will be the ones who can afford the expensive studios. Peckham doesn’t need that: it needs space for the people who are already there. One of the aims of the Bold Home project was to positively discriminate in favour of Peckham’s Afro-Caribbean community and local artists when selecting studio tenants. It would have provided cheap spaces for all occupants – in fact ten percent of their studios would have been completely free for community groups and charities, for the full five year run.

I realise that this is, of course, all somewhat speculative, and that architectural projects as unwieldy and as unpredictable as this one rarely emerge as exact realisations of their optimistic blueprints. Plans change. But at the Pop Brixton site, a painted shipping container will reportedly cost you £900 a month to rent. Rather than offer free studios, Pop promise to donate ten percent of profits from Peckham Levels to a community fund to help local businesses. But what if they don’t make any profit? If Southwark Council had green-lit the Bold Home project instead, it would have essentially subsidized the development of nearly a thousand budding creatives, whilst receiving £200,000 a year in rent.

These days, Bold Tendencies and Frank’s are often signalled as key contributors to Peckham’s socio-economic transformation from deprived inner London suburb to cultural destination and clubber’s paradise. The neighbouring Bussey Building now boasts a top floor bar of its own, whilst once small, local venues such as Bar Story have bloated into sprawling, haircut-filled mega-bars. People charge off the overground to swill cocktails in what used to be builder’s yards and railway arches.

It’s very easy to take it for granted that Frank’s was always going to be a success. But back in May 2009 the people behind it were completely shitting themselves. One of the organisers, Sven Mundner, remembers planning for that first year. “We were worried. We knew that if we could just get forty people paying a tenner each, every evening, then we’d just about be okay. That’s about what we were planning and hoping for. We just wanted to keep people up on the roof with the work.”

Southwark Council had given Bold Tendencies the space to use, and everyone involved had stumped up their own cash to get the structure built and the bar stocked. Of course, Sven needn’t have worried.

At its heart, Frank’s Café began as just a mad idea that – crucially – Southwark Council took a gamble on. Its success is testament to what can happen when a council allows local up and coming artists and organisers to put something on themselves. Bold Tendencies evolved from exhibitions staged by gallerist Hannah Barry – and Mundner – in a squat on Lyndhurst Way, to the roof of an old council building, and finally the car park roof. It was a daunting space, but they had a bold, simple idea, and the local government backed them to make it happen.

With Bold Home, Southwark had the chance to once again take a gamble on something new; something that would generate more than just pretty photos and a financial return for outside investors.

Pop Community’s success is another example of local councils supporting commercial development projects rather than active, less profitable ones; bringing in outside investment to prescribe and curate a creative community instead of allowing the existing one to develop. Bold Home wasn’t a particularly sexy idea, but it was a useful one; an investment in the creative industries rather than property prices. The real kick in the teeth is that for Southwark, the big paycheque is coming either way, when the site is bulldozed and the flats go up. Why not give something back to the artistic community who have done so much for the economy of the area in the meantime?

The reason is, I believe, publicity. Peckham Levels will turn the car park into a visible, visitable, press release ready destination, whereas Bold Home would have been more discreet and less flashy. Conversely though, should Peckham Levels prove successful, then its visibility and status as a tourist destination, may dissuade the Council from demolishing the car park at all. Savvy councillors who want the site to evolve into a permanent art space may well have secured the long-term survival of the building by choosing Pop – and that is something to be celebrated.

But we have to ask ourselves what our city needs, and for many, the simple answer right now is cheap space. Community engagement projects are all well and good, and there’s every chance Pop will be a success, especially if they liaise with heroic local organisations like Peckham Vision. But I believe that a community that can live and work within its means doesn’t need outside help to thrive. The beauty of Bold Home is that it would have let the residents of Peckham just get on with quietly making things, whilst still shouting from the rooftops.

Credits

Text Tom Harrad

Photography Loz Pycock