Drew Carolan remembers the first time he saw a group of skinheads. It was the fall of 1981, at 2:30 on a Tuesday morning. He was walking along Avenue A, and noticed the skins outside Tompkins Square Park. “They were maybe 14 or 15, tossing a frisbee and laughing hysterically, just like it was recess,” Carolan recalls. “I’m thinking, ‘Who the fuck are these kids? They’re great-looking. I want to photograph them, but I need to figure out how.'” (In the early 80s, Carolan explains, NYC skinheads were largely not engaged with far-right or racist offshoots of the subculture.)

It was a question Carolan (born and raised on the Lower East Side) thought about for nearly two years. The answer wouldn’t come until he’d gotten far away from Tompkins and the city that raised him.

In early 1983, a 26-year-old Carolan embarked on a life-changing journey with Richard Avedon. Having assisted the master fashion and portrait photographer on his iconic Versace campaign, Carolan was asked to join Avedon on the open road. He spent the next few summers assisting on sessions that would comprise In the American West, considered one of the most important works in photographic history.

When Carolan returned from his first venture west with Avedon, he found more tribes of skinheads — this time, congregating on the Bowery, outside CBGB. Ten years prior, the grimy watering hole had incubated the city’s upstart art-punk scene, hosting The Ramones, Blondie, Television, and Patti Smith. By the 80s, it was an impossible-to-get-into club come nightfall. But on Saturday afternoons, “CB’s” hosted all-ages matinee shows for a new kind of punk tribe: hardcore kids.

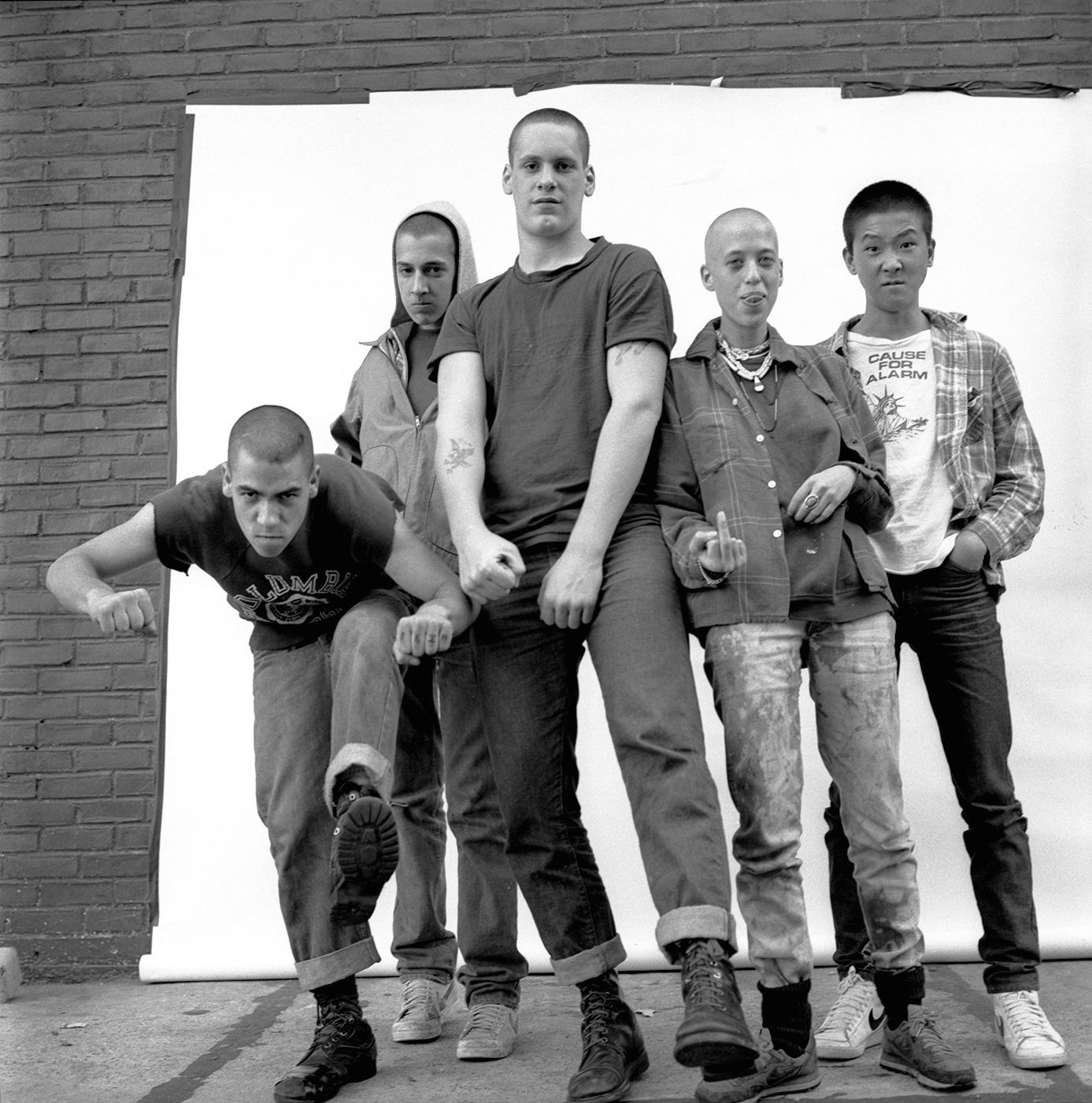

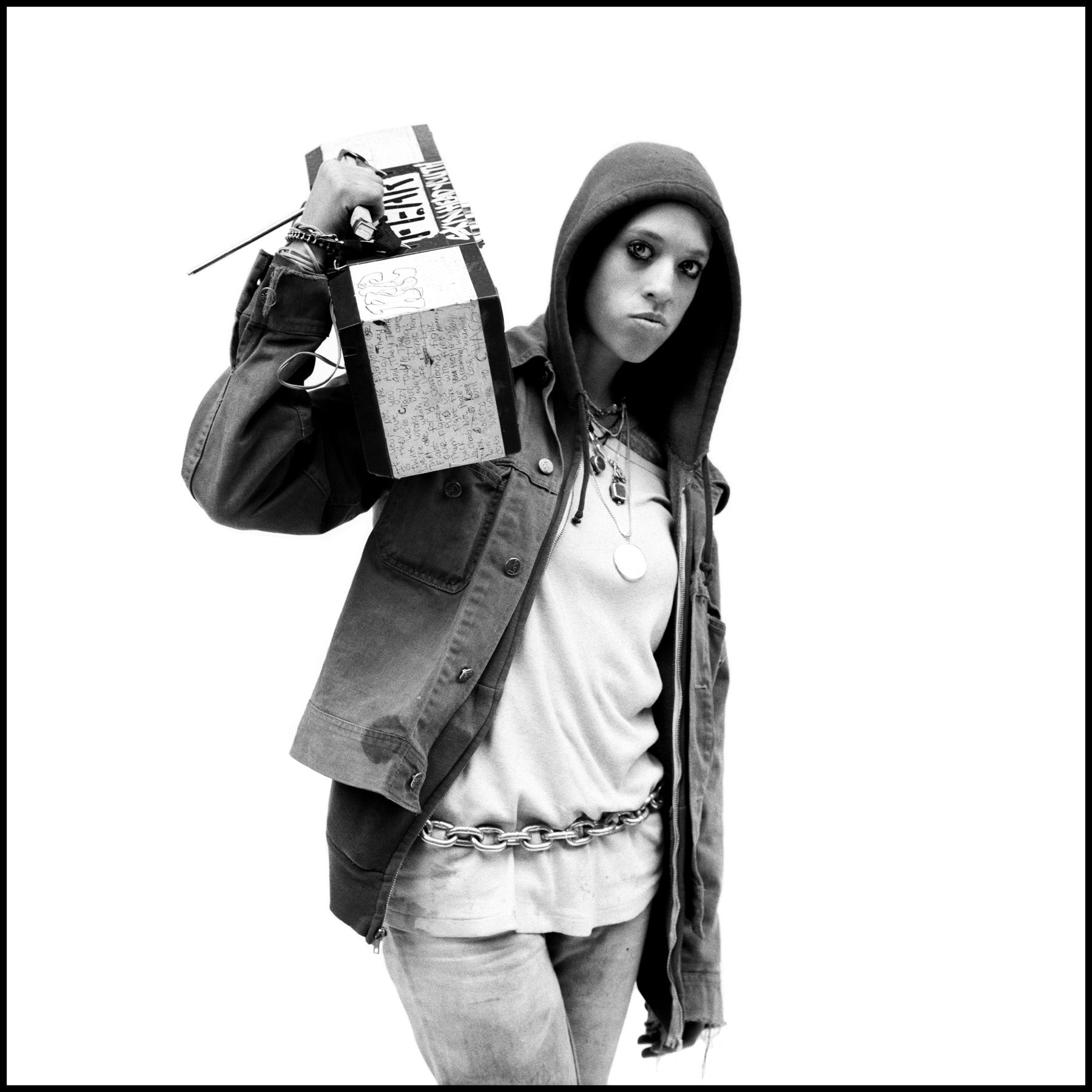

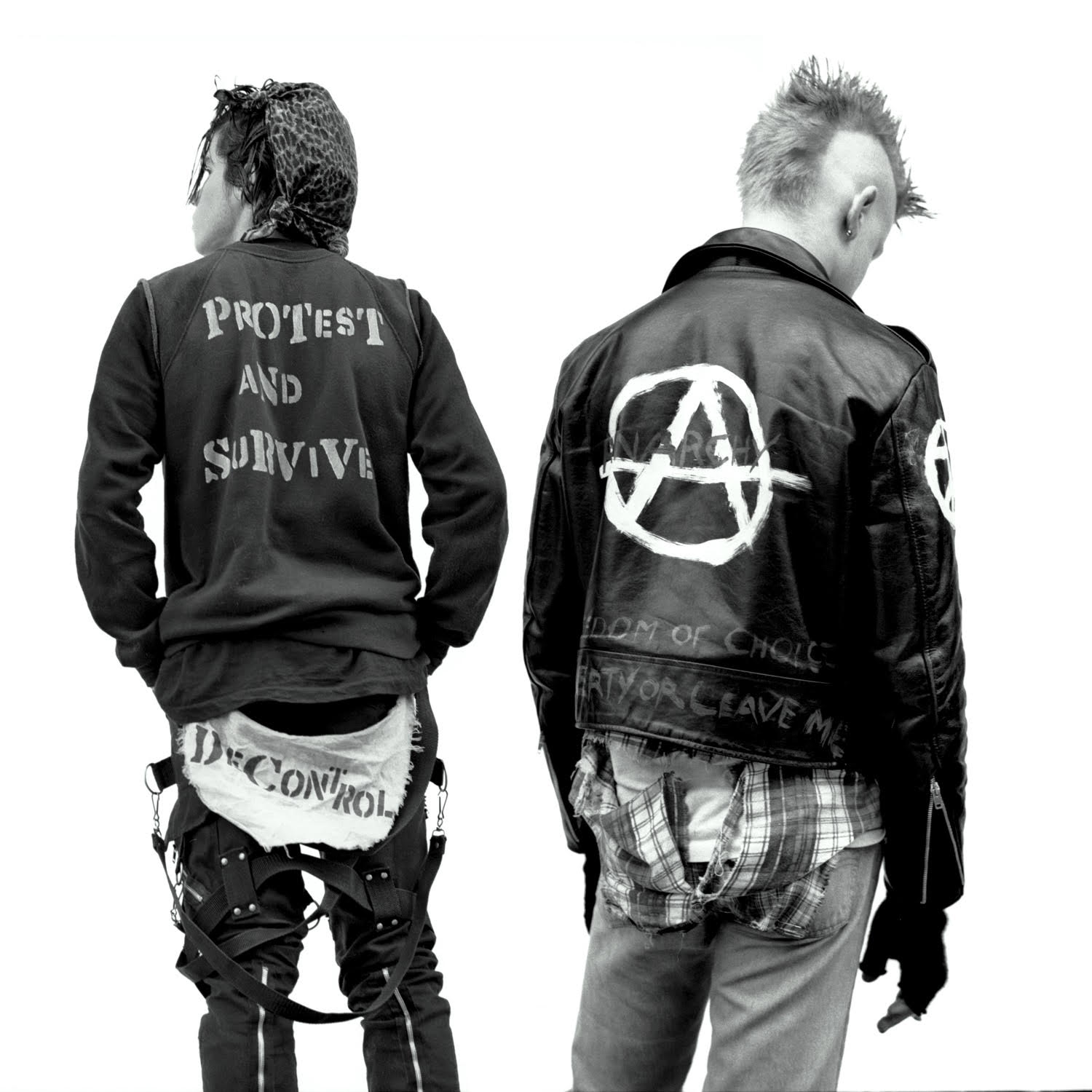

Skinheads, peace punks, and runaways from across the tri-state area descended upon CB’s each weekend to catch sets by Agnostic Front, Cro-Mags, Murphy’s Law, Reagan Youth, 7 Seconds, Minor Threat, and countless other bands. Beyond musical mayhem, it was a thriving subcultural ecosystem, where kids from all walks of life could connect with each other and blow off steam — take a break from the world outside CB’s walls, a place that often wasn’t safe or accepting.

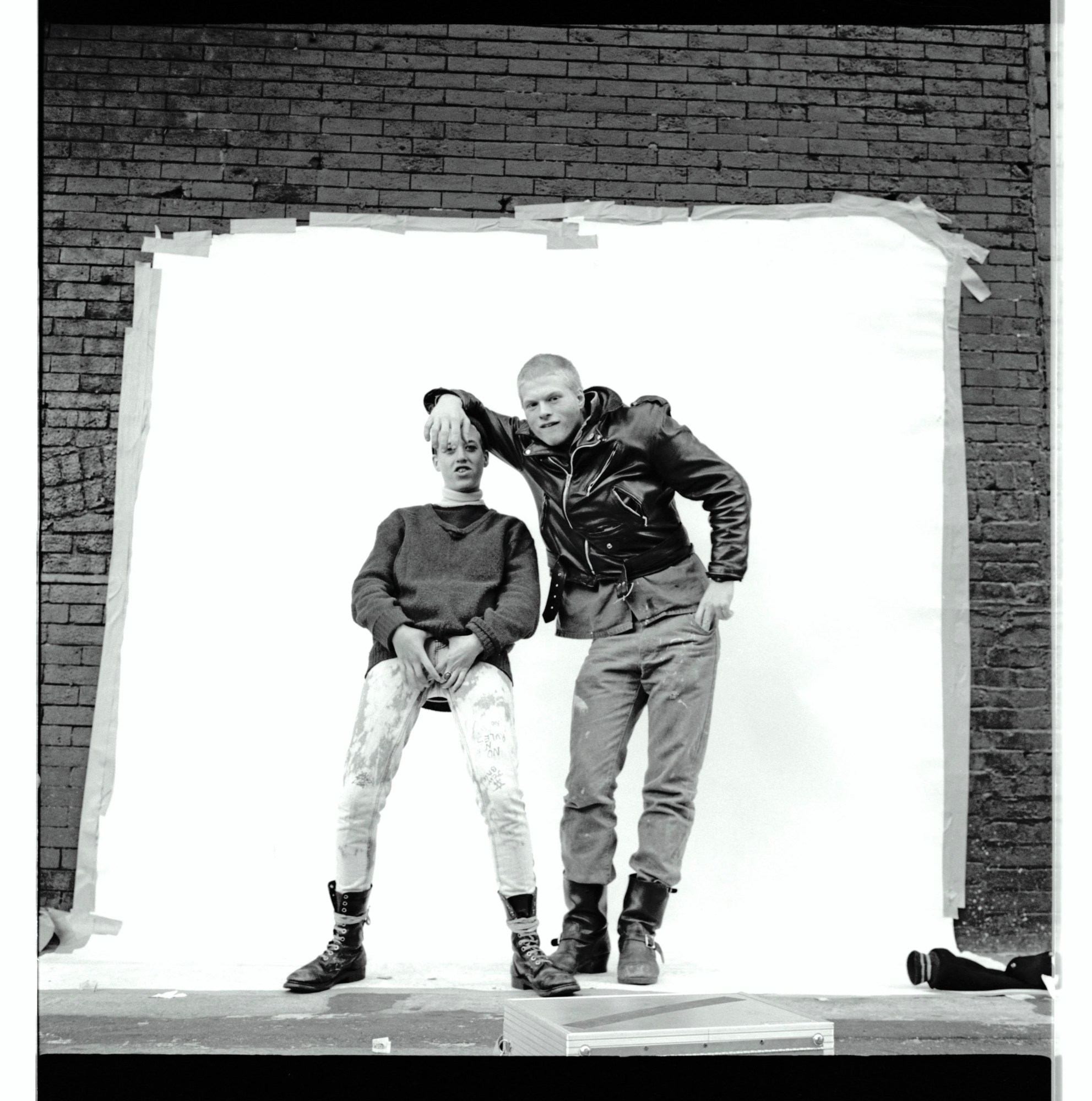

As he’d done for Avedon out west, Carolan taped a large piece of white paper to the side of a building across from CB’s. He spent the next two years intercepting kids on their way to matinees, photographing them with a medium format Rolleiflex.

“With Avedon, it was much more of a romantic notion. He would photograph someone and say, ‘He’s like a Botticelli,’ or ‘He’s like a Vermeer.’ I’m thinking, ‘My guys look like fucking maniacs!'” laughs Carolan. “It was a different approach. I just wanted to get an honest picture. Because look: when you’re 17, I don’t care how cocksure you are. You have doubt, you have vulnerabilities. You’re trying to figure things out. To me, it’s very real. I was that! When I was 17, I had the answers to everything. But when I’d come home and be alone, it was a different story.”

It’s this empathy that makes Carolan’s portraits so special and true. He captured the vitality, vulnerability, rebellion, and fierce sense of community that united the scene. Over 30 years later, he’s collected the pictures in the newly published book Matinee: All Ages on the Bowery. The work is outstanding — the definition of an instant-classic.

How did your interest in photography first develop?

When I was maybe 14, I started doing modeling jobs to make a little money — how I got into it was pretty bizarre. But anyway: I was on a job, an editorial for some publication, and started talking about music with the photographer. At that time, I was 15, almost 16. I was going to a bunch of shows; I was so into it. The photographer was telling me about shooting The Kinks, Rod Stewart. I thought, “Wow, that’s so cool. You photograph bands, you know, on top of doing this stuff. I gotta do that.” The photographer turned out to be Bruce Weber.

What!

He was so nice! He said, “I can always use assistants, so give me a call whenever.” I kept his number, but I moved out to Long Island the last couple years of high school. When I moved out there, I had great teachers; they were right out of college and really into art. I started doing photography with them, and I really got into it. I went to SUNY New Paltz and got a BFA in Photography. When I got out of college, I started freelance assisting photographers. Eventually, I did do freelance with Bruce for about a year in the early 80s.

How did you start working with Richard Avedon?

I had a few friends who did freelance assisting too, and knew somebody who worked for Avedon. He said, “We’re doing this big Versace campaign. We need somebody to run around, get coffee and shit.” I got hired for about two weeks to work on that campaign. It was fun! A little while later, they called and said, “We’re looking for a full-time assistant. Do you want to do it?”

I was making better money at restaurants and freelancing by that point, but they told me: “He’s doing this book In the American West. He’s gonna be traveling through the highways of the Western United States over the next two and a half summers.” I said, “I’m in!” The joke was that the furthest west I’d been was 4th Street! It was a life-changer, I’m not gonna kid you there. It was just unbelievable.

Avedon photographed people by going out to an event. A rodeo, a wood chopping jamboree, a rattlesnake roundup — the kinda shit they had out there — where people would just come out of the woodwork. He’d set up an outdoor studio on the shaded side of a building, and just pick and choose people.

I went by CB’s one day on a Saturday in 83, and all those skinhead kids were out during the middle of the day. It turns out that CB’s was having these hardcore matinees in the afternoons. I said, “Oh man, this is how I’m going to do this. I’m going to go across the street on Bleecker, set up a studio, and intercept these kids on the way to the shows.” Seemed perfect. I had gone to CB’s back in like 75, 76, and I’d gone to high school a couple blocks away. I knew the area, I was comfortable there. I was one of those kids, you know what I mean? It was all because of working on that project with Avedon that I was able to come up with a way to execute what I wanted to do.

Tell me about the New York hardcore community at the time.

Hardcore was such a small scene. And when I discovered it, it felt like it was just starting. The CB’s matinees started on Saturdays, but later moved to Sundays. The shows normally started around 2:30 or 3, and they’d go to maybe 5:30 or 6. It was three bucks to get in, and there were always at least three bands.

The first day I went down there to shoot, by myself, I had this 9-foot seamless that I’d walked from my basement studio on East 11th Street. I set up and shot a bunch of pictures. When I got home, processed the film, and looked at the contact sheets, I saw a picture — which is the cover of the book — and I knew I had to keep going. I saw a decisive moment. This whole group of kids, and what they were about, I found fascinating. Because it wasn’t punk; it was hardcore! It was a different scene. They really had something to say.

One day, I was packing up and went inside CB’s. Kids were moshing, having chicken fights, it was mayhem. It was just communion-like — something I’ve never seen before. A really great display of teenage camaraderie, angst, and everything all rolled up into one. I was hooked from the first time I saw a band! Some of the music was awful [ laughs] but it didn’t matter. The fact that you could get up there and blow off steam for two hours was great.

Did you ever encounter racist skins at CBGBs? Everyone quoted in the book emphasizes that melting pot, all walks of life, united aspect. It doesn’t seem like racist ideology would have incubated. But just curious if you did, and how others responded to it if so.

Skinheads in the hardcore scene when I was there, they were all great guys and girls. Certainly intimidating-looking, but there was a real unity. And I think that was brought on with Agnostic Front: ‘There’s no justice, there’s just us. Blind justice screwed all of us. There’s no justice, there’s just us. We need justice for all of us.’ That was kind of the vibe. You’d have to be really, really crazy to be a racist skinhead and walk into a place like CBGB’s, because it really was a melting pot of kids from all over the place. I’d heard stories, in Roger Miret’s book, in Harley Flanagan book, they talk about at City Gardens, there were some racist skinheads that showed up at a show and started knocking boots. All the regular skinheads just beat the living shit out of them. I had never seen that, or never felt that vibe, ever at CBGB’s.

How did you select the kids that you photographed? What drew you to them?

The first time I went down there, it was like, “Alright: I’ve got this big set-up, I’m over here, they’re over there.” I knew I had to go over and find somebody, break the ice. I walked up to this kid Tony — a Puerto Rican skinhead with a big, three-week-old scar on his head. I said, “Hey, man. I’m doing this book on the matinees. I’d like to photograph you.” He just looked at me and said, “Are you a cop?” I said, “Fuck no!” So we went, and that was pretty much it. I never asked anybody again! It just kind of happened.

In all honesty, I was expecting to see a lot of white guys. But there are just as many girls and people of color in this book. Tell me about the diversity of the New York hardcore scene.

If I had done this in — and I’m not putting any town down — let’s say Milwaukie or Phoenix, I might not have had the same result. But New York City is a true melting pot. There were black kids, Asian kids, Pueto Rican kids, Italian, Polish, male, female, gay, straight, confused — that’s what made the scene great! It was a really nice cross-section of kids. There were kids from Connecticut, Long Island, all over the tri-state area. They just wanted to be a part of it.

How did living under Reagan shape the kids?

Having a Republican in office means young people have to fight harder, scream louder, to have their voices heard. I don’t know if the hardcore scene would have been as intense if Mondale or whoever had been elected.

What was it like revisiting these pictures after 30 years?

Around 2006, I’d gotten an email from a kid: “My name’s Andy, I don’t know if you remember me, I was one of the mohawk kids you photographed at CBGB.” I said, “Andy, of course I remember you!” We started talking, and he told me he’s still in touch with a lot of the kids. I told him I’d like to get in touch with them, too. This was right when MySpace came out, so I made a MySpace page of matinee photographs. Within two weeks, I’d get people saying, “Holy shit, I remember that!” “There’s so-and-so, he’s dead now.” It was unbelievable. Every time I got an email or a response to a picture, I got a little more inspired. So I started to seriously think about putting the book together. But it was an arduous process.

I had been approached by one company who said they wanted to do it. At the time, I’d have done it with anyone — a dog food company! We had some great meetings, but then they just stopped calling. It was a blessing in disguise, I think, because then I hooked up Radio Raheem Records, an all-hardcore label. They were really into the integrity of that scene, and wanted to be a part of the book. I’m really glad I went with them. I think this book needed to be done by an independent little company, because it’s what that scene was about.

I made a dummy book years ago, and most of the choices in that book are in this one. So the things that I saw then haven’t changed. The only difference is that once I started to reconnect with people, I got to know kids in the book. Up until then, a lot of them were two-dimensional icons, and they became more three-dimensional.

In the book, you write about a time when you basically told Robert Frank to beat it.

[ Laughs] I’ll give it to you straight: it was a cold February, I think 1984. I had kids coming, and my friend Tom assisting me. There was a guy with a huge video pack on his shoulder. He was kind of dishevelled, walking around and filming the bums across the street. He came over while I was shooting, and started shooting over my shoulder. I kinda looked at him, then looked at Tom and said, “Get that fucking guy outta here!” Tom walked him across the street, and told him if he came back over, he was gonna kick his ass!

When we were done, I was kneeling down putting my equipment away, and this guy came back. I heard this scraggly voice, “Ah what are you doing, an August Sander-type thing?” When he said, “August Sander,” I thought, “Whoever this guy is, he knows what the fuck he’s talking about.” I looked up, and it hit me just as he said to me: “I’m Robert Frank, and nobody tells me where I can go, I’ve been living here for 30 years.” I was like, “Oh my god! M-m-m-r Frank!” And he just walked away.

I realized later I had judged him in the way that other people might judge the kids. He was kinda disheveled and I treated him with disrespect. With the kids, their outward appearance is aggressive and they’re making a statement. But a lot of times, you just look at that outward appearance. There’s so much more to them.

Drew Carolan’s ‘Matinee: All Ages on the Bowery’ is available now via Radio Raheem Records. Carolan will sign copies at Generation Records on November 18. More information here.