This article originally appeared on i-D NL.

The story of the first encounter between Jochem Brouwer and Remsen Wolff almost reads like a fiction novel. In 1990 the 18-year-old Brouwer was working as an intern for a photography shop in Amsterdam. One afternoon the American photographer Remsen Wolff walked into the shop and had a chat with the owner, mentioning that he was looking for an assistant. Brouwer wasn’t there, but he didn’t hesitate for a second when the owner called and asked him if he was interested: he got on his bike immediately and hurries to the shop. The two clicked, and the 51-year-old photographer invited him to come and work for him in New York. Brouwer was bursting with excitement, but his parents don’t want to let him go. “We all went out for dinner so I could try to reassure them,” says Brouwer. “I remember my father saying: that’s nice and all, but I want to see a contract first.” I thought that was embarrassing, but Remsen totally agreed. He made a contract in which it was stated that I would be getting an hourly wage and paid accommodation, and that I would have to pay for my food myself. I signed and we left shortly after that.”

After that first journey, eight more trips to America would follow. Brouwer worked with the photographer for five years – he assisted him on his project chronicling drag queens and transgender people, which he shot in Amsterdam and New York. Wolff died in 1998 after a short period of illness, but the cooperation between the two did not end there. Brouwer inherited Wolff’s entire collection – 200,000 photos, forty years of archive material – plus an assignment: showing his work to the public. Brouwer has since kept the prints and negatives in folders that fill the bedroom and living room of his apartment in Amsterdam-Noord. 21 years later, Wolff’s death wish has finally come true. Part of his series was on display at OSCAM this year, in honor of Amsterdam Pride.

Hey Jochem. Remsen Wolff is not extremely well known, despite his enormous oeuvre. Can you tell us a bit more about him?

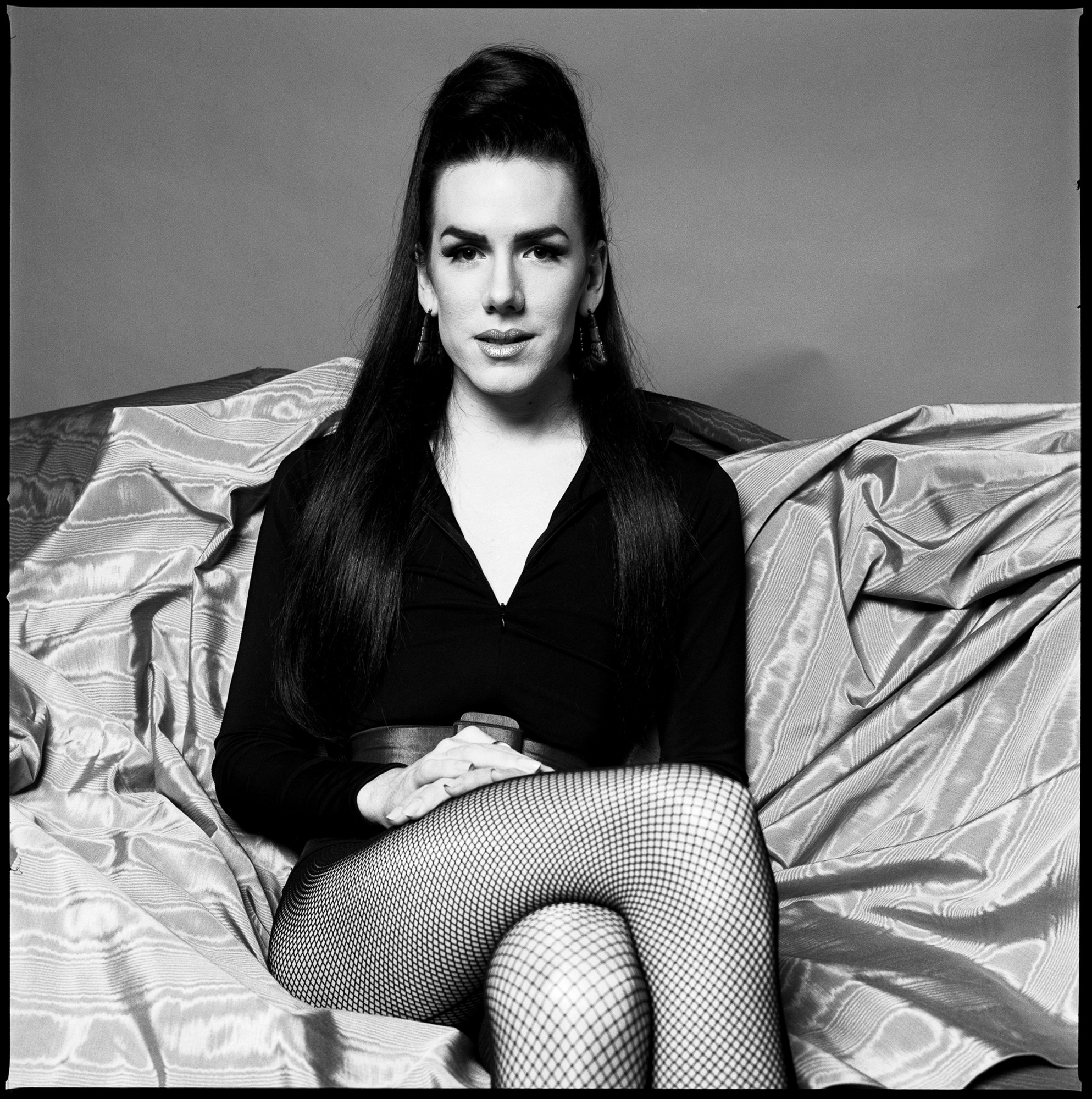

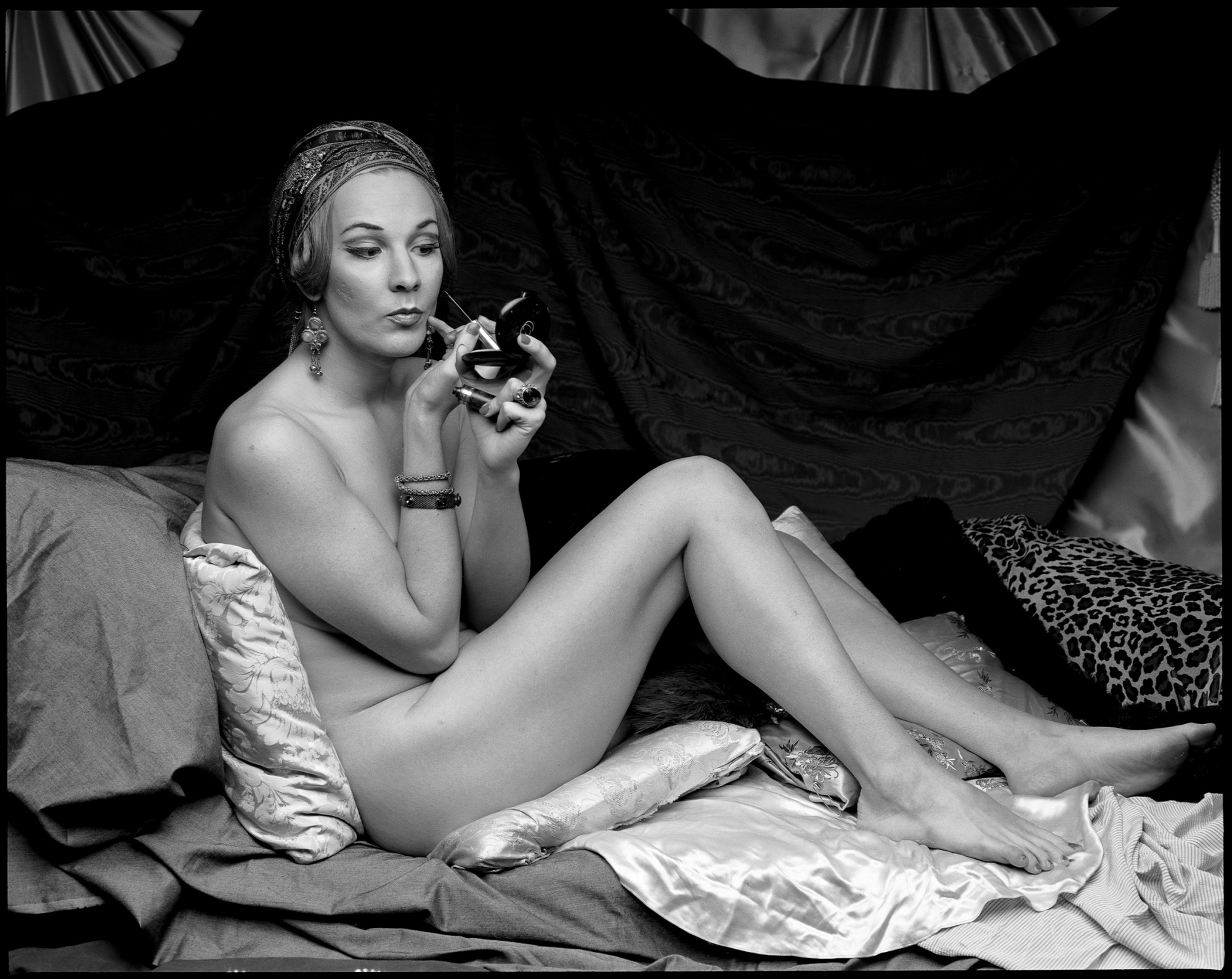

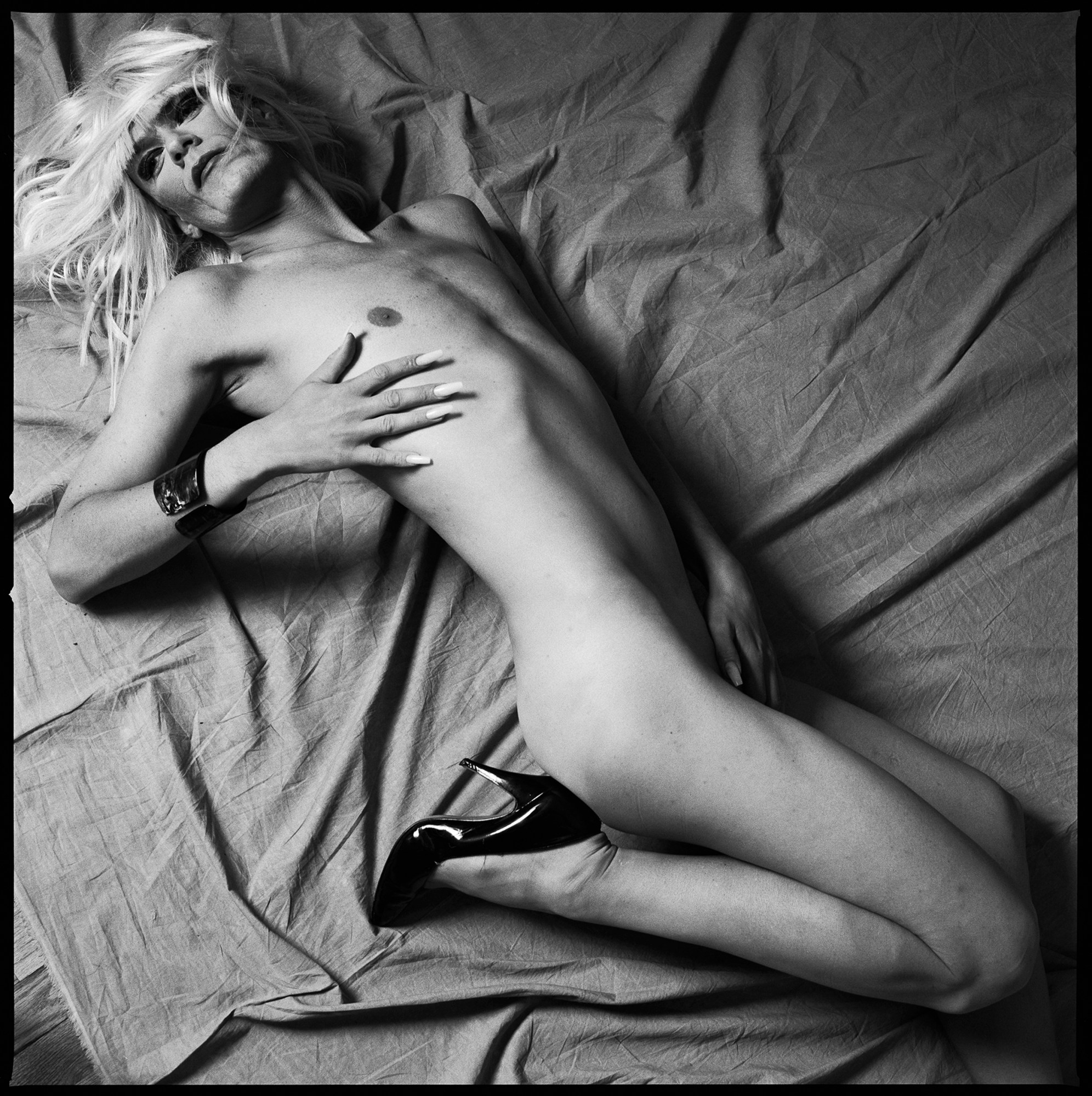

Jochem Brouwer: Remsen was a photographer and poet from New York. He grew up in a wealthy family – Isabel Bishop, a well-known painter, was his mother; his father was a professor. He studied art history at Harvard himself. He had been taking photos since he was ten, but he never turned his passion into a professional career. Yet his camera was his anchor, some kind of armor that helped him fight his agoraphobia and venture out of doors. His queer and gender identity were a true struggle for him and he was a loner. He was in his forties when he came out of the closet – he had a wife and two daughters at the time. The personal struggle inspired him to fully focus on groups that also felt different. He started portraying transgender people and drag queens, aiming to celebrate them and place them on a pedestal, which resulted in the series called Special Girls – A Celebration.

The photos are stunning. How come Remsen has never become famous?

That’s mainly due to Remsen himself. He lived an isolated life and wasn’t good at selling his own work. I would describe him as an intellectual recluse. His work never brought in any money.

Why was he so reserved?

His past played a major role – I only figured this out later. In the 1980s he lived in Texas, where he was wrongly accused of a series of murders. During a theater performance, the police found him in the audience and arrested him. Recordings of his arrest were broadcast on television shortly after that. Remsen appeared to be innocent. He sued the channel and received a million dollars in damages. Making money was no longer a priority and he could devote his entire life to photography.

What a story! How did you react when he told you?

I was shocked. He only told me after I had known him for several years. I had always known something was up, though. When it came to work, he was a big spender. He stayed at the American Hotel in Amsterdam for months. His flights were first class, and when photoshoots were finished he always made sure the models could get the best snacks and wines from his fridge. He really used the money to fully devote himself to this project.

How did he meet his models?

He put advertisements in the gay paper, met his models through people he knew or scouted them in clubs such as The Webster, The Limelight and Tunnel. We frequently went out together and we would meet the most beautiful, colorful characters. But Remsen didn’t photograph just anyone – a true interest in the person was crucial. His project was always story-centered and he was genuinely interested in what people were doing.

Are there any models that will always stick in your memory?

So many of them. When I was 21 I met Kabuki Starshine in a club. I will never forget the moment I first saw her. We were allowed to take photos of her and shortly thereafter she was scouted by Thierry Mugler. She would become the makeup artist of Sex and the City later. I’ve been checking out her work ever since. The fact that we were able to work with her at such an early stage of her career remains special to me.

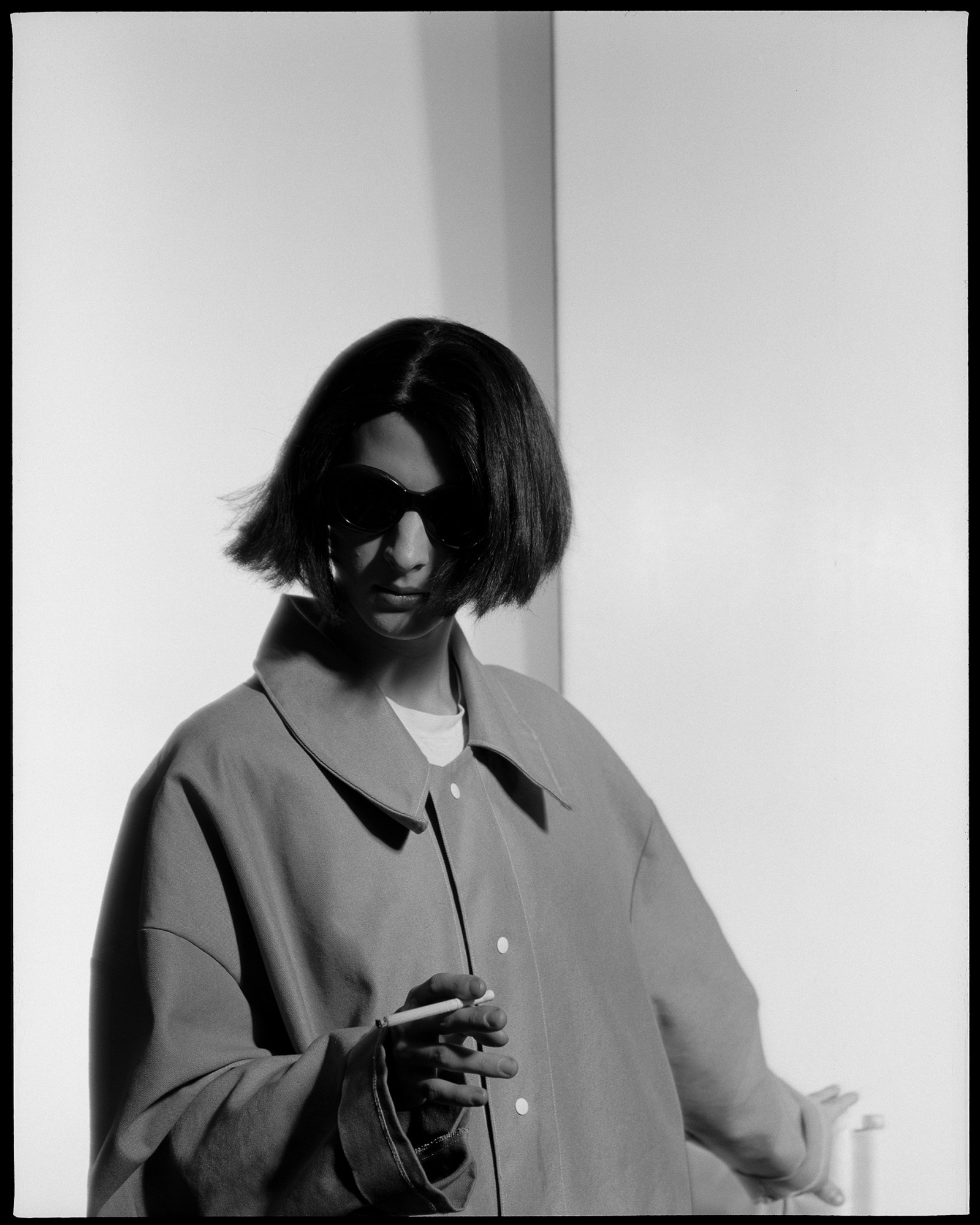

Living in New York in the nineties must have been interesting. How did you experience this as an 18-year-old?

They say youth is wasted on the young, but I feel like that doesn’t apply to me. I made the most out of these years. But it was a turbulent time, too. I’d say the nineties in Europe were relatively gay-friendly, whereas New York was swarming with gay bashers: people who would simply beat up gay people. When I arrived, Remsen immediately gave me a whistle – whistles were within the community so everyone could attract attention in case they felt threatened. He asked me to call him whenever I needed a place to sleep, which made me feel safe. He fulfilled some sort of father role at the time.

Did you see him as a role model too?

In some respects, yes. He has had the most influence on my life apart from my parents and he is one of the people who have made me who I am today. My self-confidence grew because he gave me considerable responsibility, even though I was only eighteen and didn’t know New York that well. I arranged everything for him: shootings, materials, even upgrades to better rooms at the hotels we visited. Every few years he’d be itching to change environments, so I would help him move to a new neighborhood in New York. He was a bit unworldly, and I became his mouthpiece, someone who sorted things out for him in the “real world.” He always said: “Efficiency Jochem, always efficiency.” I still think that to myself regularly, haha.

After his death, he suddenly left you with the greatest responsibility ever.

No doubt. He left me with his entire oeuvre, a bag of money and the mission to show his work to the world. I mean, that’s quite something. Things were tough at the beginning: it wasn’t until 2001 that the archive really became mine, since his daughters had challenged the will. After 9/11 nobody in America was interested in the photos. I guess the world wasn’t ready for his work yet: the subject was simply not that popular in the art world. I didn’t manage to carry out Remsen’s assignment and I felt disappointed for a long time. Remsen allowed few people into his life – I felt honored that he had let me in. He was special to me, both as a person and as a photographer, which increased the pressure I felt. I am now 46 and it seems that, bit by bit, I am finally succeeding. I can barely describe how relieved I am about that.

Why do you think the world might finally be ready for his work?

His series covers themes that are still relevant today. In recent years topics such as racism and the representation of the LGBT community have been huge topics in the public arena. Remsen’s work from the nineties is important in the here and now. His photography is honest and thoughtful – the amount of time and attention he put into each portrait really shows. I have never doubted the value of his work. I just had to be patient for twenty years before others saw it too.

This article originally appeared on i-D NL.