Imagine you are not able to express yourself. But wait: maybe, right now, you feel unable to express yourself. What can you do about it? Could clothing help you change?

This was the experience of the Bloomsbury group, a loose collective of writers, artists and thinkers, which formed in London over a century ago. Recently, members of Bloomsbury have inspired a number of 21st century fashion designers, such as Kim Jones at both Dior Men and Fendi, Comme des Garçons and S.S. Daley. What influences these designers isn’t so much a Bloomsbury look. What matters are their ideas, and what they can mean to us today.

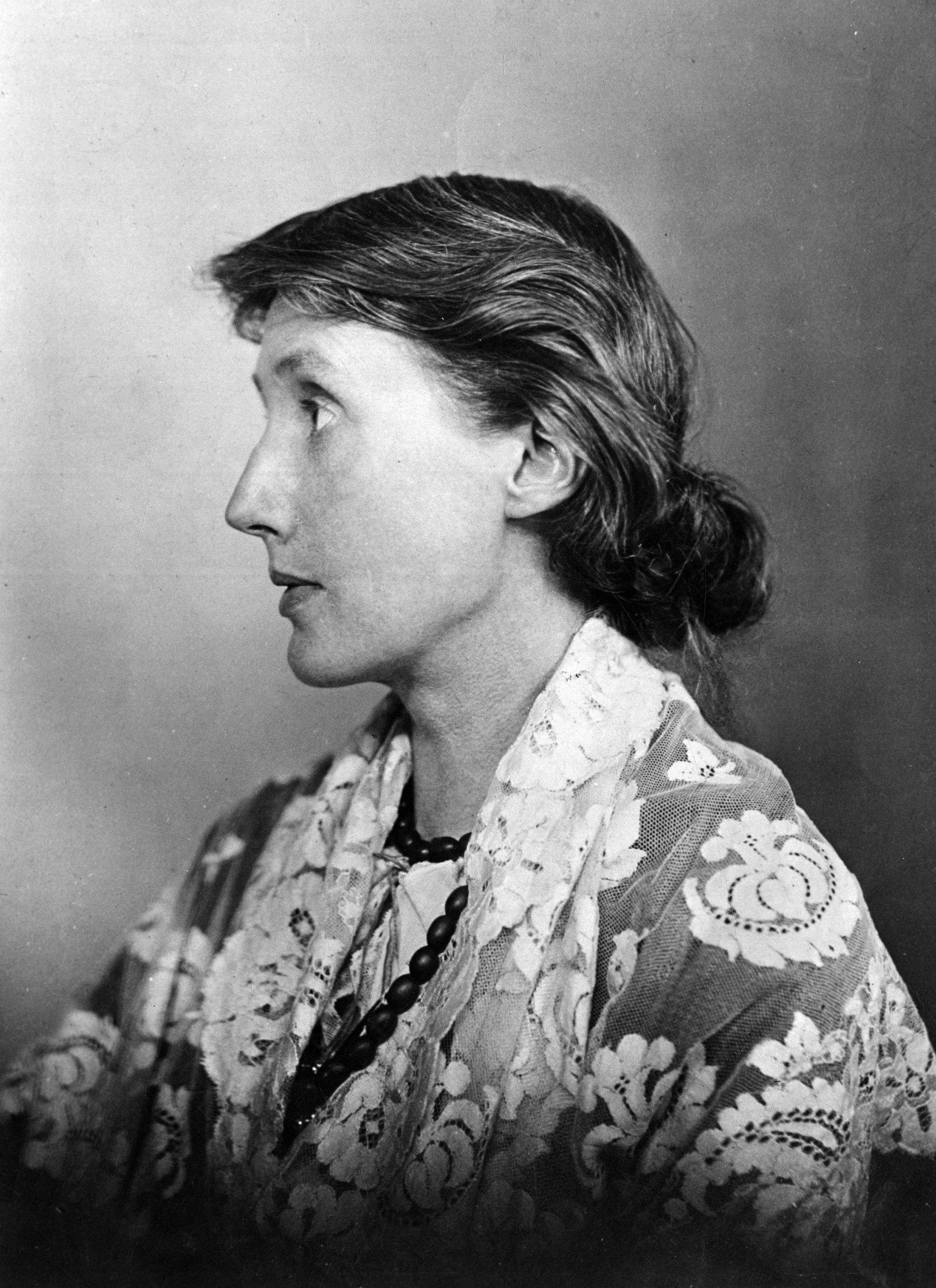

Core members of the Bloomsbury group were queer, such as writer Virginia Woolf and artist Duncan Grant. Together with their allies, such as Woolf’s sister and artist in her own right Vanessa Bell, they tried to forge new ways of living and loving.

Virginia and Vanessa had escaped abuse and psychological control of their lives, where they were expected to dress pretty and suffer in silence well into their twenties. As they revolutionised their lives, they revolutionised their clothing, creating their own vocabulary of loose, long-line, non-restrictive garments. Suddenly, they had agency.

To change our future, we must understand our past. It’s why I’ve written a book, and curated an exhibition at Charleston in Lewes, about what we can learn from the clothing of the Bloomsbury group. It’s called Bring No Clothes, words Woolf used to say to guests: we reject tradition and the conventions that trapped us. The phrase “bring no clothes” are also an invitation to us today: can we shed preconceptions about what we wear, to construct new forms of living and being?

Crucially, Woolf was not able to fully express herself. It’s known that she self-censored queer narratives from her novels, particularly her debut novel The Voyage Out, published in 1915. But also, the language did not yet exist for her to describe her style. In her diary, she described herself as “badly dressed”, words which since been taken literally, and used to mock her.

Around fifty years after she wrote those words, bad taste became the powerful fashion weapon that we know today. It happened in the seventies with punk in New York and London, with John Waters and his friends such as Divine in Baltimore, and the Cockettes, such as Sylvester, in San Francisco. i-D itself was born in 1980 to champion London club cultures that revelled in good taste/bad taste.

Today, bad taste is an understood and even sophisticated part of luxury fashion. Miuccia Prada’s work is regularly described as ugly, which is meant as a compliment. Glenn Martens gleefully pushes at taste for his work at Y Project and Diesel. We know that bad can be very, very good.

In Virginia Woolf’s time, she had no way to express this, or even recognise herself her actions. Today, we are so saturated by fashion that we can feel jaded, like there’s nothing more to learn. But what if, right now, we’re in a similar state – that we don’t even realise there are other ways we can express ourselves.

As I was writing the book, I started to make my own clothes. It was because of Vanessa Bell, who made what she wore throughout her life. I’d never tried it before, even though I’ve written about fashion for over 20 years. I presumed it was going to be impossible, but if I was going to try and understand Bell, I thought I should give it a go.

It was easy. From the beginning, I had no interest in finishing what I made properly, because Bell didn’t either. She was said to finish her pieces with safety pins, just like Jawara Alleyne, the London-based designer from Jamaica and the Cayman Islands, who has made new works in response to Vanessa Bell for my exhibition. If you free yourself from thinking you have to finish garments like they were made for a shop, you open up the possibility of intuitive design, rather than just following a pattern.

The first piece I made was a linen T-shirt with a tail like a frock coat, its collar ribbed and crewneck. The front is grey, the back in yellow check. I accidentally sewed the shoulder seams inside out. Who cares? It set my way of working, where imperfections became part of the plan. I made it over a year ago, and still wear it today.

I made other versions of the top, and kept all the scraps. Once I had enough, I patchworked them to make another, where the tail is more like entrails. I now love scraps. After I made some deadstock denim joggers, I patchworked the scraps to make an angular top, which has a protrusion like a shelf from out the back of the neck. I made no pattern, just trusted my eye. It fits me just how I like it: close but not tight, slightly awkward, a bit like it shouldn’t exist.

This is the thing: if I went into most shops and asked for something that looks “a bit like it shouldn’t exist”, I’m not sure I’d get very far. What I’m wearing only exists because I’ve actively chosen to make it. I’ve no interest in starting a fashion label. I don’t want to dress others. What matters to me right now is being in communication with myself.

For the first time in my life, my relationship with my clothing is elemental. By writing the book, it’s been like breathing sudden clear air. Fashion has often made me feel at a remove, even though I’ve worked within the industry for much of my adult life. It made me think about that cliché of fashion, the sense of je ne sais quoi. It implies that a key quality of being fashionable is something that can’t be known.

This not-knowing has long been a tool of consumerism: we keep buying more in the hope that the next thing will finally give us, too, that je ne sais quoi. But what if all the mystery of fashion is just an illusion. What if we can know, and have agency over what we wear.

This led me to find another way of looking at fashion, other than the usual cycle of seasons which create their own remove, because fashion seems perpetually one step ahead. Instead, at the end of the book, I suggest a new philosophy of fashion based around the tension that is inherent in every single garment.

It’s the tension that’s built into garments through the weave of the fabric, the way it’s cut and constructed. But then it’s also the tensions that we feel: interpersonal tension, sexual tension, the societal tension of if we fit in or stand out. There’s class tension, socio-political tension, environmental tension. All of these tensions are within the garments that we wear, yet they mostly go unnoticed. It’s the same as Woolf, not even knowing that being badly dressed could be a very good thing.

If we can begin to understand these tensions, maybe we can break free from preconceptions about what we wear, bring no clothes, and begin to feel more able to fully express ourselves.

Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion will be available from Dover Street Market and all good bookstores on September 7; Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion will open at Charleston Lewes on September 13.