Two days before the New York premiere of KIKI, a documentary about New York’s youth-led ballroom scene, the film’s cast is gathered in a midtown dance studio for a teach-in of sorts.

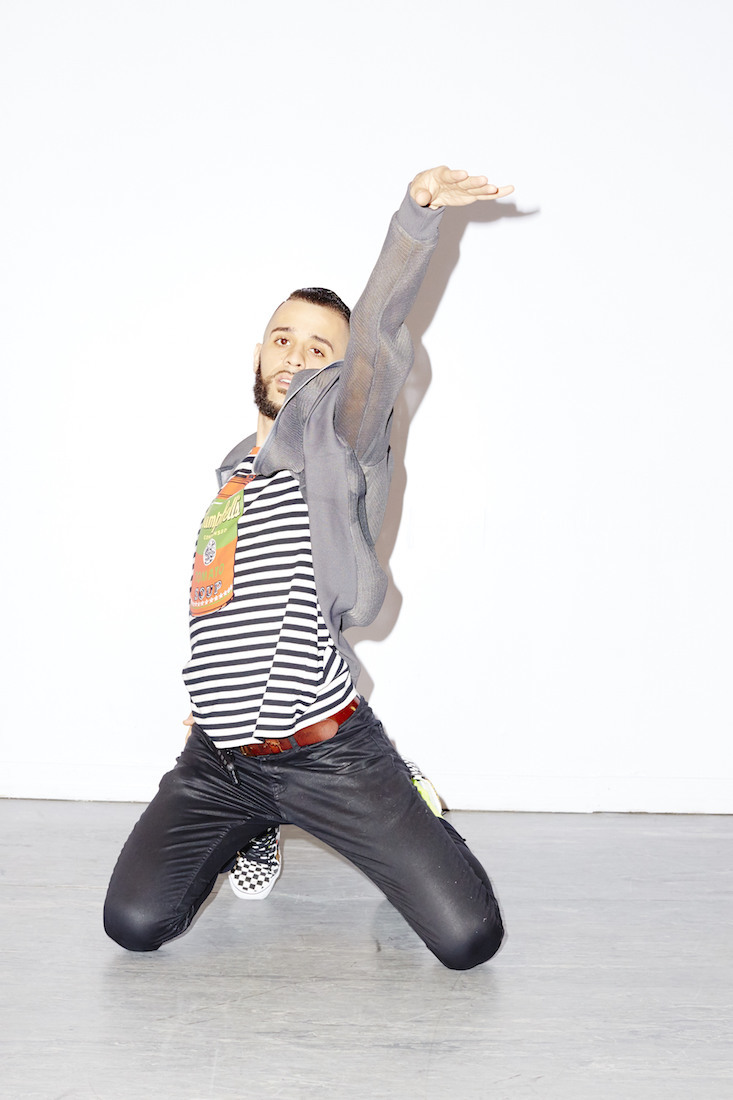

“Who’s going to tell my moment?” asks Chi Chi Mizrahi, one of the kiki scene’s originators and a legendary ballroom performer. He looks expectantly at his friends and family. Someone has asked the cast members to describe the best “effects” (essentially, looks) they’ve ever pulled off during a ball. Chi Chi tries again louder: “Anyone want to tell my moment?” “Ok, fine, well I was carried in like Jesus, strapped to a cross,” he says, “And I won. Of course.”

While the ballroom culture documented in Paris Is Burning, in 1990, thrives off extreme theatricality, and its competitions now boast cash prizes of up to $10,000, the youth-led kiki scene, founded roughly 11 years ago, is “softer,” says KIKI‘s director, the Swedish visual artist and filmmaker Sara Jordenö. The word “kiki” means, loosely, to hang out and have fun — something which the film captures, fly-on-the-wall style, during footage of kids dancing on New York’s Hudson River piers and competing in electric, extravagantly costumed runway battles in high school gymnasiums and community centers across the five boroughs.

Started by ballroom scene members who were also active in community-based organizations, the kiki scene was born as a more approachable entree into mainstream ball culture. But it’s also a way to connect often hard-to-reach LGBTQ youth of color with services like health care, HIV testing, and housing assistance, as well as hormone treatment for members of the trans community.

“Sometimes there’s no place for us,” says Gia Marie Love, who narrates her own experience of being a young trans woman in the film. “Kiki, ballroom, it’s a place for us. We might have nowhere else to go.” Later, she describes her personal favorite kiki effect, highlighting the different production values involved in kiki versus mainstream ballroom. “It was in a high school in the Bronx. And I was naked except for this sheer dress, and I had to run past the basketball court like this,” she says laughing and arranging her hands like fig leaves, “because there were actually boys in the middle of a game!”

Gia is one of several scene members who tell their stories in KIKI, direct to camera. “Paris Is Burning is the historical precedent for [KIKI], as a film about the ballroom scene in the 80s, and it captured some very important people — Pepper LaBeija and Venus Xtravaganza, for example — and I’m grateful for that,” says Jordenö, “But we wanted to make this film in a different way. What’s important is that we wanted to make not a film about this ‘secret world’ that we’re peering into. It’s a film about seven people. It’s a character-driven film, it’s a coming of age film. They’re present in this world.”

From the start, KIKI has been a collaboration — both between Jordenö and her co-writer, scene gatekeeper Twiggy Pucci Garçon, and also between the two writers and the community at large. Twiggy approached Jordenö about working together a little over four years ago. At the time, Jordenö was camped out in the office of the Harlem non-profit where Twiggy and Chi Chi worked, conducting interviews for another project.

“We knew she was a filmmaker and visual artist, so we introduced ourselves and approached her about doing something — not knowing it would become a full feature documentary,” he says. “We talked and we talked, we got to know each other personally and formed a bond and a friendship, and a level of trust. So we agreed that if we were going to do something then it had to be a collaboration in order to be successful. We’ve been very intentional about getting feedback and insight and even direction from the community itself.”

The cast is also quick to stress that the documentary is a truly inclusive project. When the film screened at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year — where it won a Teddy Award — Jordenö remembers a moment when someone asked her, “‘So you’re the vessel that [the cast] spoke through?’ and I said, ‘No!,’ and Twiggy and Gia and everyone were also immediately like, ‘No.’ It was a collaboration with a lot of mutual respect.”

The stories Gia, Chi Chi, Twiggy and the other cast members tell are all unique: scene regulars Divo and Zaryia grapple with homelessness; Chi Chi narrates his exploration of his gender identity; another of the film’s main subjects, Chris, explains how he used to watch ball videos on YouTube in secret at his family home as a teenager. The common thread is the revelation of acceptance they all experienced when they discovered the kiki scene.

During the workshop, Chris relates how he reached out to Twiggy through social media and, after hours of soul-baring phone calls, asked him to be his mother. Twiggy later took Chris to his first ball. “It was like Alice going into Wonderland,” he says.

Chi Chi remembers a similar feeling his first time: “I walked into this room — all these people and costumes — and I was like, ‘Finally, these are my people! Where have you been all my life?'”

The inclusiveness of kiki provides a safe space — often the only one available — in which young LGBTQ people can feel out and express their identities. “As a young adult growing up, exploring my identity and gender identity, I was a cunty little thing,” says Chi Chi, “Because that’s what you see and that’s what the portrayal of being gay was — that femininity. When I came into [the ballroom scene], I was able to realize what makes me happy. And also it’s healing. I’ve healed so much by telling my story and having people tell me their stories — being able to vocalize it rather than having it bottled up and driving you crazy.”

Now, when he performs — which he does in the dance studio, along with vogue legend Omari Mizrahi — he usually works “pum pum shorts and a heel.” “Someone’s gonna love all this cuntiness,” he whoops, after a jaw-dropping showcase of the building blocks of vogue: hand performance, cat walking, duck walking, spins, and dips.

“To kiki means to have fun,” says Jordenö later over the phone. “But this film was never just about entertainment. It’s for a lot of different audiences, for a lot of different uses.” In addition to the Teddy Award, KIKI recently took home the Kathleen Bryan Edwards Award for Human Rights at a film festival in North Carolina. “It was really weird to go there with everything that’s going on in that state,” says Jordenö, “But it really meant something too.”

For her, making the film also brought to light issues she didn’t know existed, or at least issues she had never witnessed first hand. “I’ve lived in New York for 13 years now, and I’ve never been stopped by the police but when we were filming, you know, with three youth of color on the street, the police are there in seconds,” she remembers. “There’s a lot of oppression. So that’s why it was really important to be recognized with this award.”

For Twiggy and the other cast members, KIKI is a platform for issues they’ve lived through and continue to battle. “I have this belief that we can’t address issues if people don’t know that they’re issues,” says Twiggy. “Then after people are aware, we can start having a conversation about it — and not just on an interpersonal level. Larger than that, we need to have an ideological conversation around acceptance, around dispelling homophobia, dispelling transphobia, about recognizing the multiple levels of oppression that contribute to creating these problems in the first place.” Premiering the film in New York, as part of the Red Bull Music Academy Festival, is another important step towards increasing consciousness — importantly, in the scene’s hometown.

As they talk, the cast and filmmakers come back again and again to the fact that ball culture, and particularly voguing, has become an object of intense fascination within mainstream culture. “It’s trending,” says Chi Chi, miming air quotes. KIKI is, in a sense, an antidote to that — to what Gia describes as “the violence” of ads or music videos that include voguing without employing born-and-bred voguers who’ve come up through the scene. “They can do it,” she says, “But it will always be missing something.” For her, kiki is community and self-expression and acceptance. “It’s therapeutic performance,” she says, “We do it to heal and survive.”

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Phtotography Sam Evans-Butler