Relegated to “women’s work” or “domestic handicrafts,” sewing, weaving, and quilting have long been excluded from the Western art canon. But in the 1960s, artists such as Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago sought to reclaim and re-contextualize the mediums. “It is crucial to understand that one of the ways in which the importance of male experience is conveyed is through the art objects that are exhibited and preserved in our museums,” Chicago wrote in the book Women and Art: Contested Territory. Today, contemporary artists are increasingly turning to weaving to express and record their own experiences: Kayla Mattes creates brightly colored tapestries of remnants from the early internet; Erin M. Riley explores her sexuality through woven naked selfies; and Laura Rokas weaves empowered portraits with glaring eyes and dagger-like nails. i-D talks to six such artists about their work, how it challenges what weaving has traditionally looked like, and if they still consider it “women’s work.”

Laura Rokas

“My work tends to bounce from medium to medium, [and] is currently comprised of painting, drawing, photography, ceramics, quilting, and embroidery. There is an idealistic quality suggested through my use of a wide variety of materials and their juxtaposition. The hierarchies and histories of these materials become compressed in a way that ditches concepts of ‘craft’ and ‘women’s work.’ First and foremost a painter, my approach to weaving is based on aspects of painting, rather than the functional and pattern-based characteristics of weaving on a loom.

“Textile arts are painstaking by nature. I slipped easily into the role of a weaver as my work often has masochistic tendencies in both process and imagery. To create a tapestry, a single piece of thread is wrapped around a frame and hours upon hours are spent weaving through the warp with a needle. My weavings are overtly non-functional and I prefer them stretched taught on their frames. The imagery that I use is just as dramatic as the method: flowing jet black hair, blood red nails with points like daggers, glaring eyes, blood, dark skies, tears… My work focuses on both moments of pain and pleasure, reducing them to graphic images and imbuing them with an operatic gravitas.”

Erin M. Riley

“My work is a continued and evolving reflection on my daily life. I collect images I send to lovers, images from the news, arrests, politics, and through submissions. I try to talk about the complicated truths that most people live with, be that trauma, death, addiction, pleasures, or the mundane… I’m not totally sure why [weaving] got [characterized as ‘women’s work’] in the United States, but typically, it has been supported, maintained, and taught by women. Possibly, this is because so many things were considered ‘men’s work’ and exclusionary, that women jumped on the opportunity to excel at the totally useful, challenging, and satisfying task of weaving. Many spaces were off limits to women, minorities, and [certain] classes, and therefore, they did with what they had. That doesn’t mean these practices were their first choices, but the ones they had and thrived with… We have to be more malleable with our ideas of what is possible. The value of a process is not contingent on the amount of cis men practicing it, and thus ‘women’s work,’ in an equal society, is not derogatory.”

Samantha Bittman

“I was intuitively drawn to weaving, and as I learned more about the complexities of weave structures, the more I became fascinated with the idea that I could build a picture out of the threads themselves. The image and the object are one and the same with weaving, and this really resonates with me… Weaving has looked — in the literal sense — a lot different throughout its history and across cultures. However, in the past 60 years, and particularly in the past 10 years, it is becoming common within mainstream contemporary art. Many galleries show artists that weave, there have been numerous museum shows focusing on fiber art, and nearly all major art fairs include some weaving… I think that it is still a signifier of women’s work, but it’s less commonly an actual domestic practice done by women. [Because] more and more artists are weaving in their studios and in schools, [it] is pushing the medium forward. People are becoming accustomed to and thinking more deeply about weaving, the conversation is expanding and diversifying, and yet the history of women’s work is part of that.”

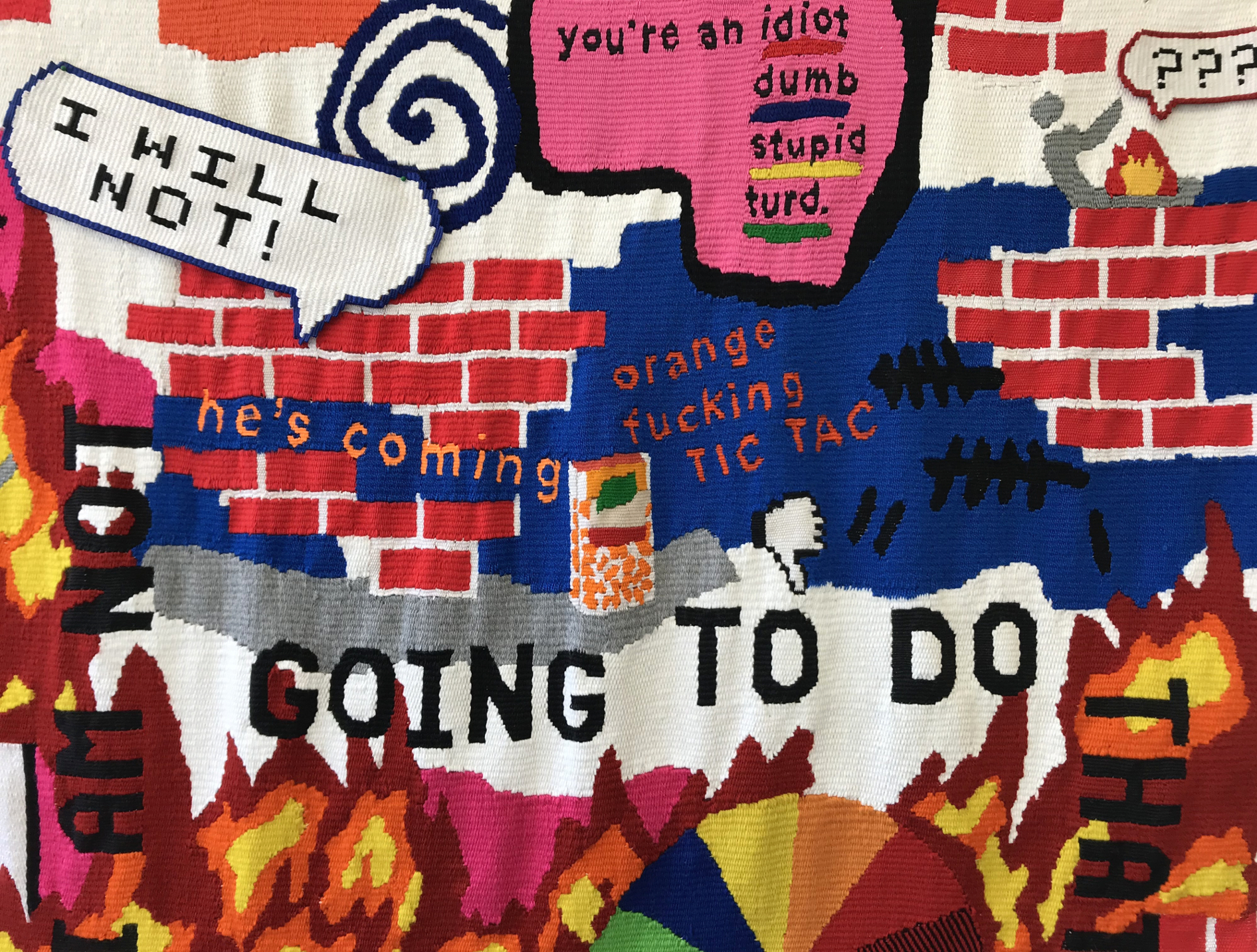

Kayla Mattes

“My recent work employs humor, text, naiveté, and urgency to craft sly political messages through the interconnected threads of tapestry. I’m interested in using weaving to make sense of the chaos of the present day, often through the lens of digital culture. In many ways my work follows tradition. For centuries, tapestry has been used across cultures as a medium to archive history through woven symbols and as a political tool for women to express dissent. At the same time, I’m interested in subverting tradition, whether it’s by simply dismantling the rectangle, or through the contemporary imagery and language that I depict within the weave.

“There’s a lot of historical baggage regarding the separation of art and craft, a split that’s definitely tied to gender. Weaving is typically lumped into the craft category and therefore overlooked as void of conceptual rigor. Soft materials are disregarded as feminine or cute. In reality, weaving is a complex mathematical process that influenced the development of computing… I’m interested in making work that blurs the binary lines of art versus craft. I believe that craft and art are interchangeable. Weavers are artists and artists can weave.”

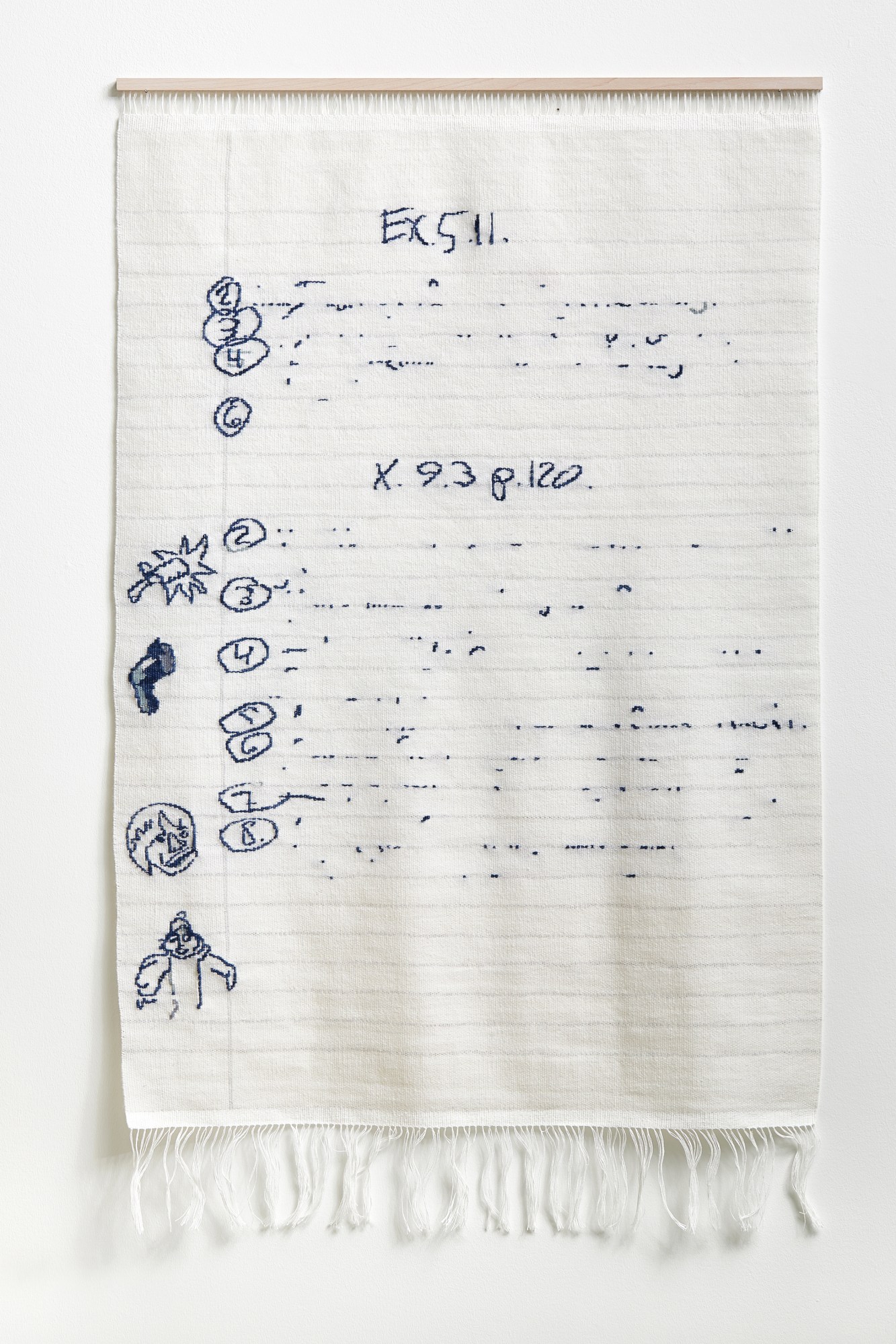

Arna Óttarsdóttir

“My approach to weaving is, I suppose, a little naive. I’m self-taught and have ‘only’ been working with it for the last eight years or so. Learning the technique, and everything that goes with it, has been a slow process (maybe because the method itself is slow), and I can’t say I’m that knowledgeable either about the technique itself or about its long history. First and foremost, the practical aspects of it interest me, the method and the slowness of it, and also the material itself. I do like that weaving is connected to women and craft, but those things aren’t a driving force behind my work.

“One of the many things that interests me about weaving is how it’s very monumental and mundane at the same time. The subjects for my woven work are often sourced from everyday life or things that seem unimportant: small and crappy sketches and all kind of doodles are blown up and used in large tapestries. And it can also be the other way around: a handwoven dishcloth inspired by the works of Agnes Martin. I’m interested in the tension between what is considered precious and the insignificant, both in relation to subject and materials.”

Linnéa Sjöberg

“For the last three weeks, I have managed to renovate my grandmothers old loom — it hasn’t been active for over 50 years! And it was my grandmother’s old rag rugs that were my starting point five years ago. [For her rugs], clothes were cut-up and [separated] from their function, and then weaved back together into a new format and thereby archived. With a similar approach, I have conducted a series of tapestries made from varied sources: a luxury wardrobe of a businesswoman, my childhood clothes, the Deutsche Welles archive and my friends’ wardrobes.

There is a performative aspect to weaving: who do I become behind the loom and who sat here before me? For the last two years, I have been researching the construction of the loom and learning old techniques in weaving and color-dying wool through historical re-enactment. The author Selma Lagerlöf [best] described the psychological aspect of weaving in The Saga of Gosta Berling: ‘If she would only set up a loom, for to weave is a comfort for all sorrow, it absorbs all other interests, and has been the saving of many women.’”