Tops and bottoms, femmes and mascs, lipstick lesbians, chapstick lesbians—there are countless multitudes and little gay nuances that make up the lesbian identity. But one particular figure within the community has become increasingly overlooked, even endangered: the power lesbian. In an opening line from Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw narrates, “The power lesbian, they seem to have everything: great shoes, killer eyewear, and the secret to invisible makeup.”

In the ’90s and early aughts, the power lesbian was visible and defined. At large, think Ellen DeGeneres, Rosie O’Donnell, Jenny Shimizu, Bette Porter, and Tracy Chapman. These were the talk show hosts, musicians, actresses, and fictional icons who exuded competence and charisma. In everyday life, the power lesbian showed up as the art gallerist, the stylish stockbroker, the restaurant owner, the woman in the tailored suit jacket and heels, working in a male-dominated field, and excelling at it. But where has she gone?

It’s not like we’re losing lesbians entirely, albeit the recent exits of JoJo Siwa and Fletcher to their boyfriends as minor casualties. Still, if online discourse is any indicator, especially on TikTok, the women-loving-women community is experiencing a noticeable dip in clear, resonant representation. What was once a vast and varied spectrum now feels increasingly collapsed, leaving certain sectors of the community, those who once felt seen and powered by that archetype, directionless.

“I feel like in the ’90s, the power lesbian really spoke to a lesbian or a woman’s proximity to capital, proximity to respect, proximity to money. We have a Reneée Rapp, we have a Chappell Roan, we have a Kehlani — I don’t know if the word is power,” says lesbian Nia Stanford, a director and podcast host of “Glass Closet.” While not all power lesbians were public figures, many were deeply invested in building something of their own, not just in their professions, but in their identities.

In contrast, the lesbians who currently hold cultural power, artists like Chappell Roan, Reneé Rapp, and Kehlani, are not seeking proximity to traditional systems of power, but rather, have been vocal in their critiques of them. Unlike the earlier archetype of the “power lesbian,” who often moved towards their allegiance to the capital machine, today’s queer figures are more inclined to reject those structures outright. As many queer people align with liberal or center-left ideologies, their power lies not in assimilation, but in a conscious detachment from capitalism’s rat race. Stanford continues, “Now it’s probably more about proximity to politics or artistry. I think the icons that we see today aren’t respected because they are powerful, they’re powerful because they are earnest and because they wear their queerness on their sleeve.”

She reflects, “Now, queerness, because of our current government and the broader sociopolitical shifts after 2020, feels different. So much has changed culturally that I think being a lesbian is actually cool now, and we don’t have to prove it anymore,” Stanford says. “Queerness, as a verb, resonates with far more people.”

Many celebrities who were once embraced as sapphic icons or who had headline-making coming-out moments, now find themselves tucked under the broader, more ambiguous label of “queer.” Whether it’s Hunter Schafer, Cynthia Nixon, JoJo Siwa, Fletcher, Olivia Ponton, Billie Eilish, or even Miley Cyrus in her Bangerz era, the term has become a kind of safety net. “I’ve read a lot of the discourse about a lot of Lesbians being lost to queerness [as a term], but I can appreciate and understand that sexuality is so fluid,” lesbian model Grace Valentine says. “But it does feel a bit invalidating when someone makes a big deal about wanting to be perceived as a lesbian or caters towards the community, but then just switches up [their sexual preference or identity] and they don’t really address it.” They continue, “It’s not really fair when their whole platform is built on the backs of lesbians and then they kinda, ‘oops, changed my mind,’ like, it’s okay if you like a man, just don’t dodge your previous statements.”

Online discourse about this topic of former power lesbians or figures suddenly dismissing their label of lesbianism with no explanation is nothing new. But the entitlement from their audience could be a reason as to why many power lesbians are driving away from their community. “But I understand, it’s hard because everyone, especially on the internet, feels so entitled to everyone’s business.” They continue, “Parasocial relationships have a huge role to play in that, where you’re losing a certain element of what separates you from this person. I think separation is necessary to make someone an icon.”

In the ’90s and early 2000s, lesbians were front and center in shows like The L Word and Orange Is the New Black, and films like The Watermelon Woman. Today, they’re often pushed to the background, reduced to side characters, while lesbian bars and clubs disappear at alarming rates, with a sharp decrease from an estimated 200 in the 1980s to fewer than 20 by 2020, according to the Smithsonian Magazine and Business Insider. What’s left feels less powerful: “Hey mamas” TikTok influencers and controversy-ridden podcasters who don’t quite fill the gap.

“Historically, lesbian icons were often tied to resistance, not just representation. They were people who pushed against dominant systems, and their presence meant something because it came with real stakes,” says Nathalia Dutra, founder of Lesbian Archives. Dutra thinks of power lesbians like Audre Lorde, Cássia Eller, Leslie Feinberg, and Chavela Varga. “These were people whose visibility was inseparable from their politics and the material conditions they were navigating. Their icon status wasn’t just about being seen but about the kind of world they revealed or made possible.”

Dutra says that the current state of lesbianism and its representation is “strange.” Everything is hyper-visible, but very little is felt. “With social media and the attention economy, being a ‘power lesbian’ often gets flattened into brand-building, constant performance, or a kind of digestible identity politics that lacks depth. There’s pressure to always be online, palatable, morally correct, on-trend.”

Once a cultural fixture, the “power lesbian” has become elusive, replaced by fragmented, hyper-visible-yet-underdefined versions of queerness. Part of that is because of the queer representation we currently have. “I know we mention Chappell Roan, but I don’t know how much a white woman can be a power lesbian in this day and age.” Richardson explains about how the radical nature of the term is essential to its definition.“There’s nothing radical about being a queer white woman,” says Gabrielle Richardson, queer gallerist and model. “I don’t know if the power lesbian is gone, I think we will just have to change the verbiage and change it to power queers,” she says.

Dutra follows up on this sentiment, “I can’t help but think about how the internet has changed what it means to be an icon. You know, there used to be this mystique, a sense of distance that let people project their longings and fantasies onto someone. Now, everything feels flattened.” She continues, “We’re expected to be constantly visible, constantly branding ourselves. I feel like that forced self-publicity kills the allure.” To exist, the icon needs time, resonance, a kind of lingering presence that doesn’t fit into algorithmic churn. So much of today’s public image is about performance and moral capital. About being visibly good, correct, consumable.

The power lesbian isn’t extinct, just evolving. In an era defined by the anti-capitalist cool, we’re seeing fewer lesbians in the C-suite, fewer brand-aligned identities, and a move away from those subtler signifiers like structured blazers and no-makeup makeup. Still, we cling to the last of them: Lena Waithe, Sue Bird, Kristen Stewart, Karine Jean-Pierre, and maybe even Renee Rapp when she shows up in a suit.

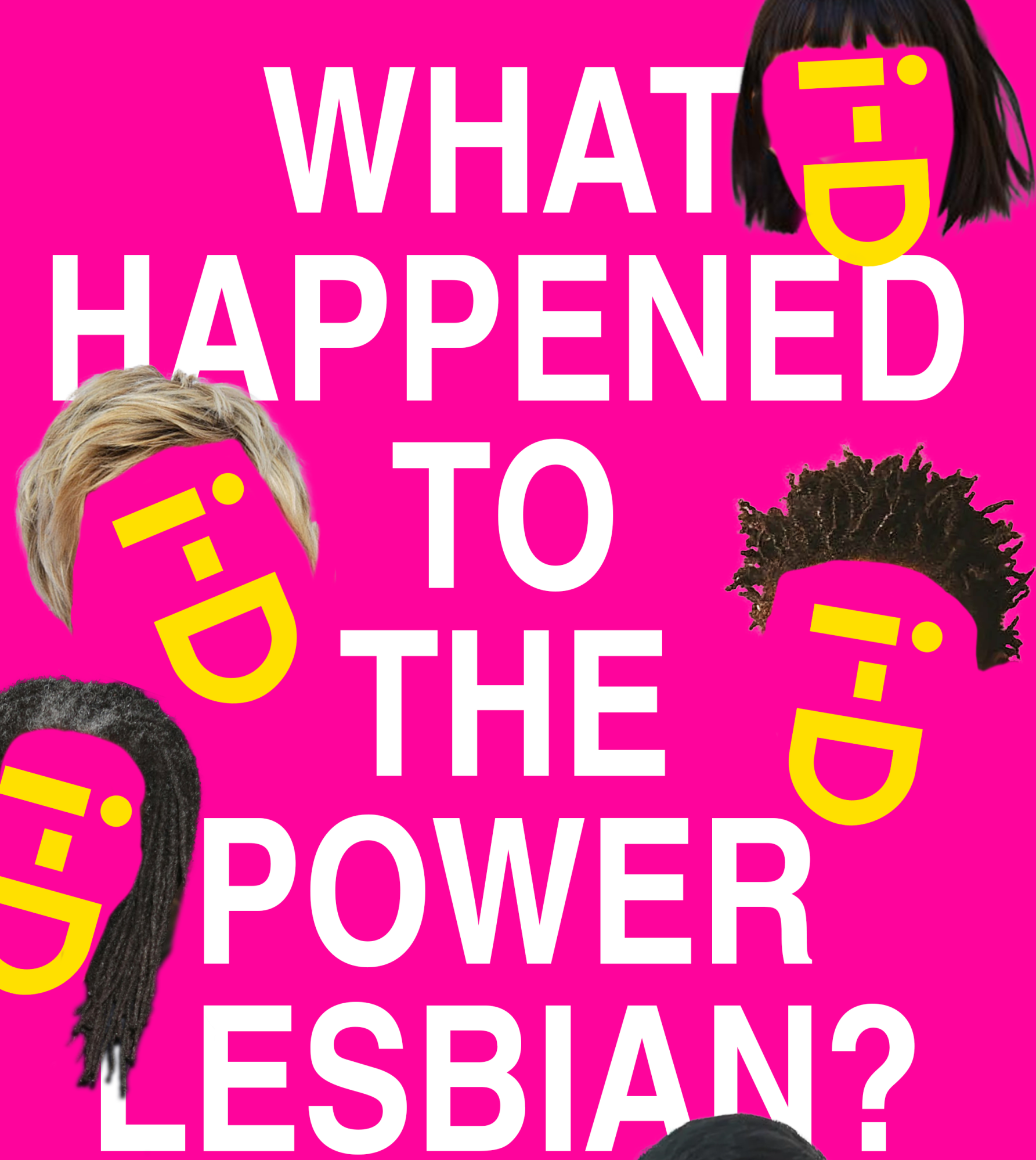

What Happened to the Power Lesbian?

Writer Tiana Randall remembers the ’90s “power lesbian,” an energy that once served as a north star for the LGBTQ+.

Share

Loading