Catherine Tramell, with her murderous vendetta on the middle-aged-or-old white man, is gainfully employed the only way that a killer of old white men should be employed: she is a writer. There’s no job more fitting. Acrimonious reception from the old and white and male establishment can harden any female; it just so happens Tramell copes by stabbing men with an ice pick. Using a pistol is far less phallic, I guess, and most writers do abhor a lost metaphor. It’s a pleasing piece of symbolism, even if it is also — yes, technically — serial murder.

Those reporting on the scene are quick to note that she always lets the victim cum first, which seems like a tender gesture. Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct is most often called a “thriller,” when I’d argue that it should be a dysfunctional romance film. Most men are happy to believe that the woman they’re fucking might kill them, if only abstractly. Many women, not coincidentally, think about killing their partners. Sex between the sexes is a perfect psychic crime: in Basic Instinct, it’s enacted as a physical and literal game, where the winner is the murderer and the loser is most often male. A ruined cop — a drunk and a coke addict, who shot two tourists in a raid, with a wife who killed herself — wants to die, even if he won’t actually say it. Obviously, his dream-girl is a murderess. The two play games like any other lovers, with the difference being that the stakes are higher.

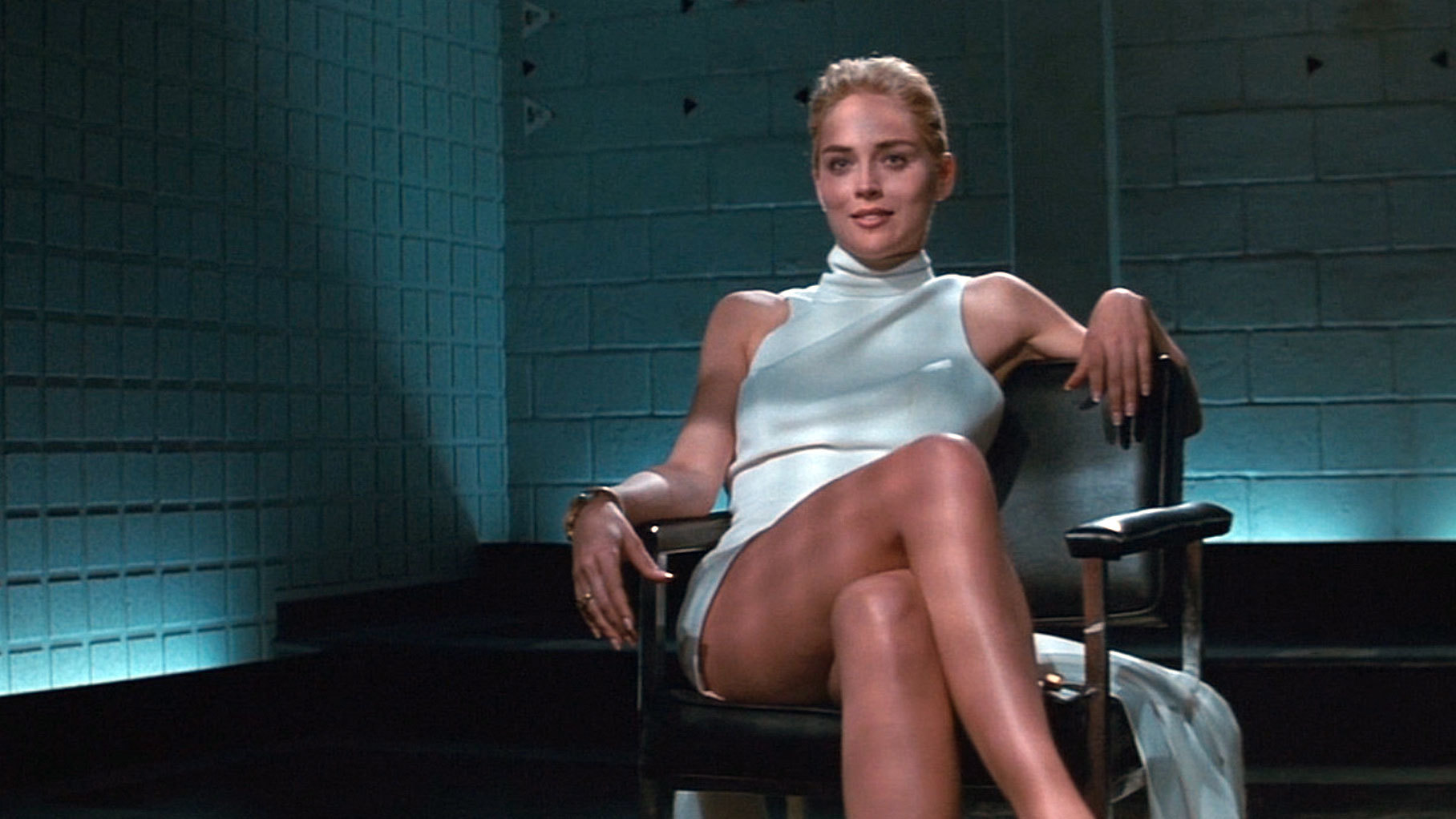

Some of these games are more startling than others. Turning 25 this year, Verhoeven’s film is never quite as thrilling as it is in its most famous scene, in which a knickerless and smoking Sharon Stone reveals her pussy to a room of suddenly dickless-seeming cops. “The ruse they use—’We have the power, we’re going to show you’—didn’t cut the mustard with [Catherine],” Stone told Playboy. “Her attitude was, ‘You’re so powerful. Aren’t you cute!’ And, of course, she had all the power. These men put her in a position where she was alone in a chair in the center of an empty room—surrounded. That would be a very intimidating position to be in unless she disarmed them, which she did. At the police station she could have been stricken and scared. But instead she thought, ‘This is going to be fun. Oh, so you want me to sit in the middle of the room here? Oh, charming. Why is that? You want to make sure you can look up my dress? OK, you can look up my dress.'”

Do not speak to me about trash talk or rudeness if you’ve never dated online, and been female; male web messaging is the internet equivalent of a ‘good cop’ and ‘bad cop’ routine

Lady Macbeth says to Look like th’ innocent flower, But be the serpent under ‘t. Catherine Tramell occasionally looks like a flower — a bougie one. Mostly, she looks like a snake; or like a flower tattoo that says, in cursive, “don’t tread on me.”Played by Sharon Stone, and with a wardrobe half by Herve Leger, half by Eileen Fisher, it can only help that she’s the heiress to a hundred and ten million dollars, which means that her work killing men is for pleasure, not profit. (Being a writer of novels is also an ideal career for a millionaire, as it negates the dread risk of starvation; playgirls only ever waste to nothing by design). Specifically, Catherine writes thrillers. She writes them under the name of “Catherine Woolf,” because Catherine Tramell — as if you did not know this already — is totally perfect. To “trammel” means, as if you did not also know this, to restrict.

And, if I’m honest, I think Catherine is a woman who’s woefully misunderstood. Have you ever tried — and I mean, really tried — to find completely seamless, truly naked-looking lingerie? It can’t be done. No wonder she prefers to go commando in white spandex. Men both verbally and literally expose their dicks with something like abandon when they’re grabbing power, so I cannot see that one vagina makes much difference. Likewise, do not speak to me about trash talk or rudeness if you’ve never dated online, and been female; male web messaging is the internet equivalent of a ‘good cop’ and ‘bad cop’ routine. I consider it more-than-nominally thoughtful that she ties her victims’ hands with a Hermes scarf, when a rope would do: you would not find this as a piece of advice in the pages of Cosmo, but I do like to believe you might find it in Vogue Paris. Something you might find in Cosmo is somebody saying, verbatim: “I liked having sex with him. He wasn’t afraid of experimenting. I like men like that. Men who give me pleasure. He gave me a lot of pleasure.”

Let’s assume that women’s magazines do not completely know the answer, which does not — to me — seem like much of a stretch. Let’s assume instead that What Men Really Want is far more complex than might otherwise be gleaned from Glamour. Good! The old ways are, for all intents and purposes, completely DOA. We’ve thrust an ice pick in them; and are freed from cooking up Engagement Chicken, waiting for the rightest time to call him back, not giving anything up on the first date, et cetera et cetera. If we no longer model ourselves on the rom-com heroine, but instead on straight, entitled men, then what might we resemble? I propose we might resemble Catherine Tramell, one of the greatest and wickedest female lovers in the history of cinema.

I cannot and will not condone obsessive dieting, but there are good and bad reasons: remaining slim in order to murder discreetly beats starving yourself for a wedding.

Here is what she preaches, should you wish to practice it yourself: lying is a part of keeping love alive as much as any other everyday domestic tic. It’s as good as self-care, or as good as extending your care to the other person. One good way of becoming adept at lying is becoming a writer, which is how I learned to say “perhaps” instead of “are you fucking kidding me.” In the police car on the way to the station, Catherine has the following exchange with a no-name cop:

“You working on another book?”

“Yes I am.”

“It must really be something making stuff up all the time.”

“Yeah, it teaches you to lie.”

“How’s that?”

“You make stuff up all the time, you have to make it believable. It’s called the suspension of disbelief.”

Everyone suspends their disbelief in a marriage or when cohabiting, largely for the sake of preserving their sanities; in suggesting that we practice lying for survival, Catherine is ahead of the curve. Keeping in shape is important, too, although perhaps not for the reasons you would think. At her boyfriend’s murder scene, the CSI guys are impressed that — despite their athletic pre-cum-during-murder sex — Catherine has not left a bruise on his body. It wasn’t the maid, they conclude, as the maid weighs two hundred or more pounds. I cannot and will not condone obsessive dieting, but there are good and bad reasons: remaining slim in order to murder discreetly beats starving yourself for a wedding.

Being up-front cuts the bullshit, so that you and your lover can spend far less time on the whole cat-and-mouse thing, and more time on sex, love, and dating; on mulling over whether or not to pick up the concealed weapon under the bed, and so on. “You’re not going to stop following me around just because you’re on leave, are you?” Catherine says to Douglas’ interested cop. “I’ll be leaving around midnight, in case you are going to follow me.” After they finally sleep together, she asks him, deadpan: “Did you really think it was that impressive?”

Catherine’s big idea is never to allow a man, or a hobby of murdering men, to stand between her and the fact of getting an education. Yes, she’s “the fuck of the century,” and with a “cum laude pussy” — but she’s also a probable genius. A double major in English Literature and Psychology from the University of Berkley, there is never a moment in which she downplays her intelligence. “I like playing games,” she purrs in the interview room. “I studied psychology, it goes with the territory.” Enviably, someone says about her at one point: “She’s brilliant! She’s evil!”

The actual fact of an unashamed and glamorous female, bisexual serial killer is hardly typical — typical women and typical love stories are often tedious, anyway.

As I think I said before, although it bears repeating: there is nothing wrong with leaving your prospective partner scared. I mean, a little scared; a little or a lot, depending on the kind of thing they’re into. “Were you frightened last night?” she asks, eagerly. “That’s the point, isn’t it?” says the crooked cop. “That’s what made it so good.” Knowing how and when to finish things is also crucial. Catherine finishes it all with “goodbye, Nick.” This does not land; her follow-up is: “Goodbye Nick. I finished my book. Didn’t you hear me?”

Reviewing Basic Instinct back in 1992, the New York Times had a good idea of who we might resemble if we ended girlie rom-com dating, and instead assumed the masculine position: we would, Janet Maslin says, end up as a bunch of copycat Material Girls. “Madonna is an obvious model for this rich, controlling woman,” she suggests, “who turns her sexuality into a form of malice, deliberately mocking and inverting ordinary notions of heterosexual seduction.” As it happens, Catherine Tramell had been based on a real, live, angry woman, who was not a pop star or a playgirl, but a go-go dancer: “she reached into her purse, and she pulled out a .22 and pointed it at me,” screenwriter Joe Eszterhas once told Nerve Magazine of their one-night-stand. “She said, ‘Give me one reason why I shouldn’t pull this trigger.’ I said, ‘I didn’t do anything to hurt you. You wanted to come here, and as far as I know, you enjoyed what we just did.’ And she said, ‘But this is all guys have ever wanted to do with me, and I’m tired of it.’ We had a lengthy discussion before she put that gun down.”

For a person who was interested in playing games because they had studied psychology, I imagine that it might be interesting that an anecdote about a woman sick of being used by men might end up as a work of fiction that’s about the opposite dynamic: but then, this is a Paul Verhoeven movie, so that rape victims are sometimes terrifying, and Bette Davis remakes sometimes come with added strippers. “Do we remember the crimes of Catherine Tramell,” Amanda Fortini asks at Elle, “or her cool composure and self-preservation?” I would say that we remember all three, if only because the actual fact of an unashamed and glamorous female, bisexual serial killer is hardly typical — typical women and typical love stories are often tedious, anyway. These days, smart girls are too killer for Cosmo. “I don’t feel,” as Catherine says, “like talking about this anymore. Now get the fuck outta here. Please?”

Credits

Text Philippa Snow