Early last week, the cancellation of this year’s LVMH Prize was announced. Given its finale was scheduled for 5 June, and the pandemic-induced global travel restrictions likely to still be in place by then, the decision came as a shock to few. Still, quietly disheartening as the news may have been for its eight contenders, there was a silver lining: this year, the award’s €300,000 grand prize will instead be divided equally among them — a welcome buoyancy aid for any young independent designer straining to keep their head above water.

Human curiosity being what it is, it’s hard not to wonder what, in a parallel universe unblighted by Covid-19, the final outcome might have been. With this year’s final line up populated by such singular, stellar talents, your guess is as good as any other. Take a look at the numbers, though, and you’ll see that it was shaping up to be an auspicious year for London’s fashion community. Cautious clairvoyance based on the number of prize-winning brands the city’s produced aside — three, for those counting — there’s the fact that, of the final eight this year, four are based there: Ahluwalia, Nicholas Daley, Chopova Lowena and Supriya Lele.

It’s hardly surprising, given the British capital’s reputation as a brimming hub for independent fashion design. But this ostensible victory comes at a time when question marks surround the industry — and the country’s — future. Even before the current pandemic was but a flicker on our newsreels, rightward shifts towards a politics of myopic isolationism were already beginning to threaten the fashion economy. The very real prospect of a hard Brexit, and its draconian restriction on migration, threatened to halt the relationships with the continent on which countless fashion businesses, independent or otherwise, rely. Now, with stark warnings of post-pandemic economic fallout, things aren’t getting any simpler for the city’s young designers.

Still, the work of the four London-based finalists in this year’s LVMH Prize proves why their voices are needed more than ever. On the surface, they have a few things in common beyond the city they call home. But these differences do, in fact, make them apt ambassadors for what British fashion, and society in general, looks like at its best: a rhizome of cultures, references and influences that are traditional, irreverent and rebellious all at once. Proud as it is of its home-grown history, British fashion is unafraid to welcome narratives from beyond its coastline to create something singular.

You find that in the artful bricolage of Ahluwalia, whose namesake designer, Priya Ahluwalia intricately patchworks vintage sportswear swatches and plaid checks, upcycled shirt fabric and vibrant geometric knits. Born in London to parents of Indian and Nigerian descent, her work acts as a foil to her experience of British identity. “I’ve always been around people from a mix of backgrounds, whether in my friendship group, at school, or at uni,” she explains. “I really love that, in London, so many cultures mix and come together. My friendship group alone has people from the Caribbean, Africa and Eastern Europe, and that’s what’s really nice about Britain.” Of course, London’s diversity, and the cultural wealth it yields, is not just down to these discrete cultural entities living beside one another. Rather, it’s the product of decades of intercultural dovetailing, of minority communities exchanging with and respectfully assimilating the tones of one another’s cultural expression, with those native to these islands as their backdrop.

Much the same can be said of Priya’s work. “I really like looking at that fusion. Sometimes that comes through in the energy, or even in the styling, or certain fabrics that evoke feelings or memories,” she says, like the subtle psychedelic laser etching and roomy tailoring of her AW20 collection, faintly reminiscent of the mid-60s. “I might do a sports top that’s inspired by someone in the 70s in Britain, but the colour might be the burnt orange of Nigerian sand. It might not immediately be recognisable as something that’s inspired by my heritage, but it all comes together.” The importance she places on hybridising elements from migrant narratives shouldn’t, however, be seen as a spurning of British tradition. “I’m interested in looking at what the cultural groups that have migrated to this country have done with their style and fashion on arrival, as well as looking at the traditional things like Savile Row,” Priya says. “It would be a dream to work with someone from there on something, but I would want to introduce narratives from beyond the world that it’s historically catered for, looking at how migrant communities have dressed and introducing that.”

Nicholas Daley echoes Priya’s sentiment. “It’s hard to define what London fashion specifically is, it’s a patchwork of so many different elements,” he says. His eponymous label riffs on gentlemanly soft tailoring, fusing artisanal techniques with the subcultural narratives for which the capital has long been a fertile ground. To him, though, the city’s celebrated contemporary fashion identity owes a particular debt to its heritage of exacting craftsmanship. “Savile Row, for example — there’s nowhere else in the world that has that level of history and appreciation. It’s the birthplace of 20th-century menswear, the Western reference point for quintessential style.” No less inspirational are the self-contained sartorial communities that have flourished beyond Mayfair’s borders, each a crucial constituent block of the city’s fashion history. “Different areas of the city have their own distinct history, too: Soho or Camden, for example, or Peckham,” he says, “and if you look at all of the subcultures we’ve had in London — New Romantics, Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Skinheads… the list goes on — no other city really has that in the same way. London has churned out more diversity in terms of music, fashion and culture than any other city in the world. That’s why so many brands, creatives and artists are drawn to it. It has a legacy.”

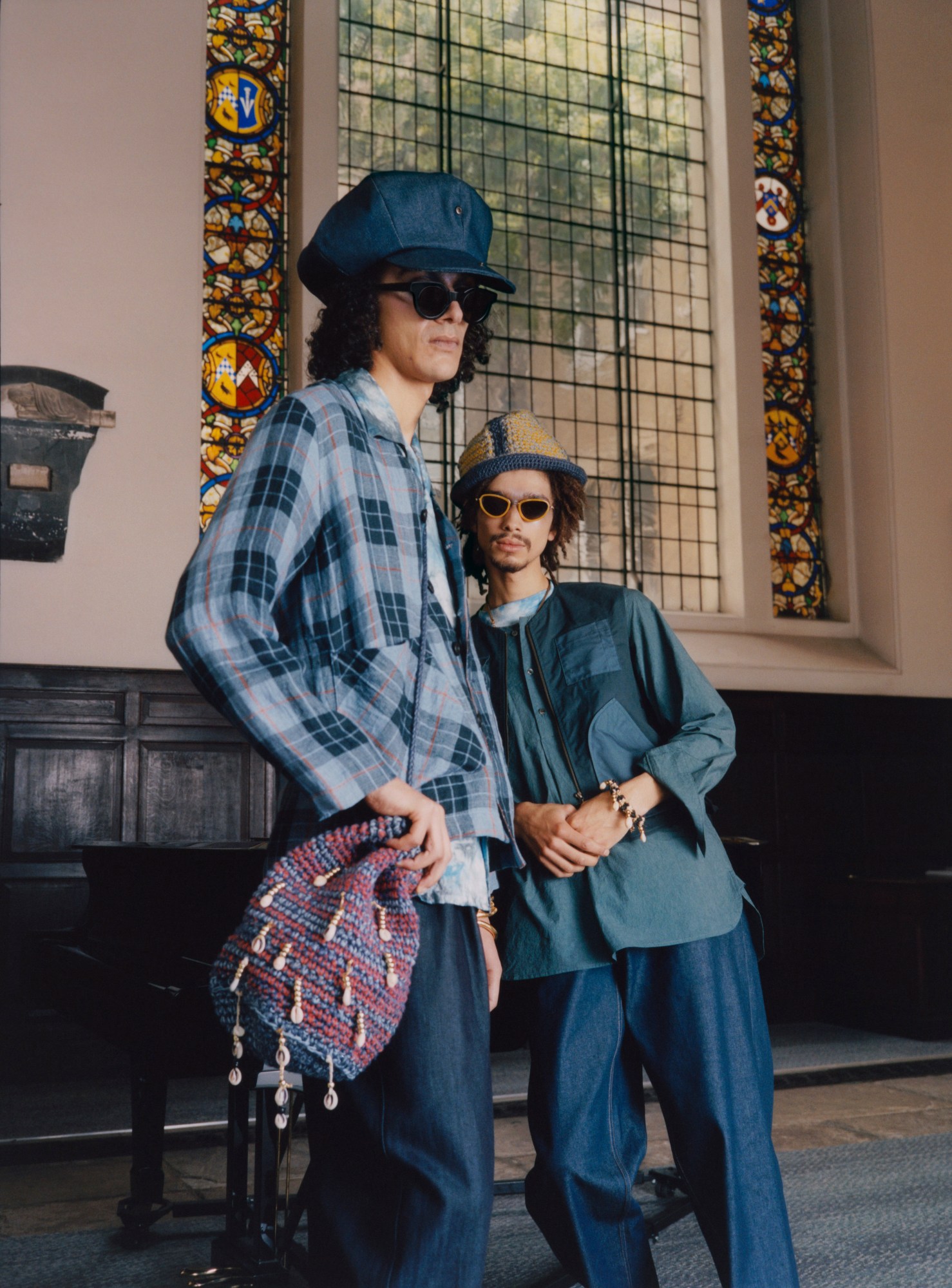

Nicholas’ work might, then, be best considered a nimble braiding of these different strains of legacy. For AW20, institutional traditions placed mohair tartans woven by Lochcarron, or quilted outerwear produced in collaboration with equestrian outfitter Lavenham, alongside Black Panther-esque crocheted berets and punk-era boots. “These heritages have brought so much to British fashion, my work is about honouring that, looking at it and pulling it all in,” he explains. “It’s about trying to pick up all these different elements of craft, history and appreciation of product and design culture, and trying to develop my own aesthetic through that.”

The mêlée of subcultures that call London home also leaves its mark on the pleated tartan skirts, balloon sleeved dresses and marble-dyed jeans of Chopova Lowena — though, like Nicholas, not at the expense of celebrating traditional ways of making. Working with a team of Bulgarian artisans, and with deadstock fabrics sourced from across the country, their practice fuses generationally passed-down techniques with a wide array of contemporary references, from safety pins, to cartoonish graphics, to the young brand’s ubiquitous climbing carabiner fastenings.

It’s in this spirit of refined eclecticism that their work perhaps best expresses the cultural ethos of their adoptive hometown. “I think also that we both come from places which are quite, well, not isolated, but where there wasn’t much culture around us,” explains Emma Chopova, half of the brand’s founding duo. “When we came to London, both of us were sponges to everything around us — the art, the cinema, anything. We’ve always loved London design and 80s culture in London and references from that era, though I think maybe those are maybe slightly more subconscious, coming through being here,” she says. “I also think that punk culture and aesthetics have been an influence, but being punk in itself is about going against the bigger movements at a period of time. I think the way we make stuff and the way we find things — the fact that everything’s different, and that we work in a bit of a DIY way — that sort of embodies that.”

What makes the brand such a quintessential expression of the city is their approach, and what drew them to the city in the first place: their education. First moving to London to attend Central Saint Martins in 2010, Emma and her creative partner, Laura Lowena, studied on both the BA and the MA, graduating from the latter in 2017 as a duo — the second ever, after Marta Marques and Paulo Almeida. “Saint Martins very much informed our practice, which is such a big part of London fashion,” explains Emma. “We very much think in the way that school taught us to think, which I think is a really great way to design.”

The unmatched range of world-leading creative educational establishments is a prevalent factor in shaping London’s fashion landscape. Home to Central Saint Martins, the Royal College of Art, London College of Fashion, the University of Westminster and Kingston University, among others, the volume of honed young creative minds in the city at any given point is near-unparalleled. “The wealth of creative talent here isn’t just extensive, it’s intoxicating,” Supriya Lele says. The Fashion East alumna, who cerebrally harmonises sheer sari drape with a hardened, Helmut Lang-esque sexiness, proposes a new vision of feminine strength, grounded in shameless vulnerability and confident subversion. “Some of my most meaningful work has come through collaborating with my peers, which is a way of working that I think London really has a monopoly on. It’s a sense of community that I don’t feel you find in other capitals and is sort of tantamount to its image as the trailblazer for innovation within the industry.”

Supriya’s work’s most powerful intrigue, and perhaps its most nuanced reflection of life in London today, is its interpretation of placelessness, and her ability to turn the sensation of cultural limbo into a self-assured identity of its own accord. “My interaction with British identity is reflected throughout my work in very much the same way as my Indian heritage. There’s a real strength that comes out of [that] vulnerability, and so I’ve always worked to make sure that my references reflect those nuances,” she says. “In the same way that I use sheer, skeletal fabrics to mark a conceptual outline of my Indian identity, England has always been reflected in the harsher elements of my clothes. The rubberised pieces within my collections, for instance, are used to unpick the utilitarian, functional aspects of traditional British fashion whilst also playing with the notions of the subcultures that I’ve championed throughout my life.”

Such complex, plural expressions of cultural identity are exactly what make the city’s fashion output what it is. “London is nothing if not a melting pot of different cultures and traditions and it’s the synergy of all of these different influences that makes the British fashion scene so intriguing,” says Supriya, underscoring that narratives from beyond Britain’s physical and ideological borders are as crucial to its contemporary identity as those hailing from within them. As Britain’s political mainstream drifts towards a territory of brutish, homogenised nationalism, these four representatives of London’s fashion community are a needed reminder of the values that make this country’s culture worth cherishing. They are all tangible testaments to the merits of plural representation and genuine cultural diversity; their work, an optimistic mirroring of what Britain looks like, and what, we hope, it will continue to be.